A storyteller's true tale

Updated: 2012-02-22 10:26

By Chen Nan (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

|

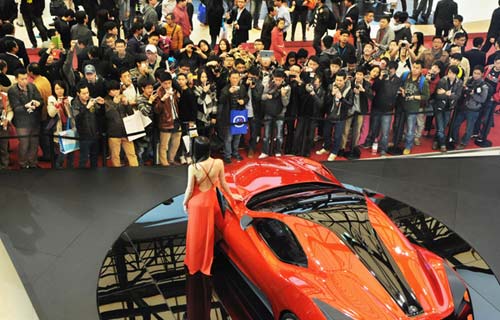

At 70, Lian Liru stages three regular pingshu performances a week. Zou Hong / China Daily |

BEIJING - Lian Liru's neighbors were right about her.

She spent her childhood in a narrow hutong in Beijing's Xuanwu district that was a hive of traditional folk artists - all of whom wanted to take her as an apprentice from the time she was age 4.

These include xiangsheng master Hou Baolin, Peking Opera master Zhang Junqiu and jingyun dagu (the art of singing in Beijing dialect while beating a drum) practitioner Bai Fengming.

Lian recalls they would say of her: "What a beautiful girl! And so talented!"

While she didn't take any of them up on their offers, Lian did become a folk performer, who has practiced pingshu storytelling for more than half a century.

She is also hailed as the first, and most acclaimed, woman performer of the northern stage art.

Lian specializes in narratives from Three Kingdoms, Eastern Han and Emperor Kangxi's Secret Adventures.

Performances feature her standing behind a simple backdrop - usually a pair of screen doors - clutching a fan and a block of wood, used to captivate the audience's attention.

Most of the stories are adopted from ancient literature, which are told with witty comments and expressive body language.

The performance art was born in the Song Dynasty (960-1279) and has remained popular, mostly in northern China.

Beijing taxi drivers often tune in to pingshu radio shows.

Lian believes she was meant to do pingshu.

"My voice is big, and I'm good at impersonations," Lian, 70, says, after her hour-long show at the Cultural Center of Xuanwu District.

More than 100 people attend the shows she performs at the venue every Saturday. The audience erupts into applause when she steps onstage, clad in a traditional red coat.

"I should have retired 10 years ago, but I can't leave the stage," she says.

Lian stages three regular shows a week. She's also preparing for the shows of Tasting Three Kingdoms, a combination of Peking Opera and pingshu at Chang'an Grand Theater in Beijing from Feb 24-26.

"You can't prepare thoroughly," Lian says.

"Pingshu is an improvisation art. Performers must immediately adjust to audiences' reactions."

Lian attributes her deep understanding of pingshu to her father, the late master Lian Kuoru. The ethnic Manchu was the most famous northern oral narrative artist of his day and the founder of the Lian School of Pingshu.

Lian was most impressed by her father's pingshu performance of Wusong, a tale of the heroic warrior from the classic novel, Outlaws of the Marsh. "Before seeing that show, I had no idea how popular he was," she says.

"The audiences were absorbed."

Lian was the youngest in her family and the most pampered by her father. She was a good student and planned to study math at Peking University. Her father wanted her to become a scholar. "My dad didn't allow me to learn pingshu," she says.

"It's a world for men. He didn't want me to struggle to earn a living."

But she couldn't contain her love of traditional art.

In 1960, Lian became a pingshu performer at the Beijing-based Folk Arts Theater of Xuanwu District, the biggest theater focused on pingshu and jingyun dagu. It was also pingshu that led Lian to meet her husband, Jia Jianguo, a patter tale (a narrative art form performed while clapping wooden blocks) artist from Shandong province.

The first step for pingshu artists is to memorize an entire book. Beyond that, the performer must develop deep understandings of the characters and plotlines, and be able to effectively convey these to audiences.

"It's like drawing a picture," Lian says.

"I use language, rather than a pen, to interpret and color the details. It's harder for women. Physically, you talk without stopping. Your voice should be loud enough to reach the last row without a microphone."

The psychological difficulty comes from acting in all the roles, she says.

"It's hard for a woman to play a man, especially a bad guy," she says.

Lian recalls her first appearance on a teahouse stage in 1961, when she performed a story from the Three Kingdoms she had learned at 17.

She went on to become the country's most celebrated woman performer of pingshu, although her career was interrupted by the "cultural revolution" (1966-76) for 12 years. It wasn't until 1980 that she resumed, at age 38.

"I almost gave up," she says.

Her husband encouraged her by performing pingshu at home every day.

"When I heard him do it, it was as amazing as the first time I heard it," she says.

She staged Singapore's first pingshu performance in 1993.

To coax audience interest, she observed the local people and their language carefully and infused it into her show. A year later, she had her own radio program in the country.

Lian and her apprentices brought the art form to US universities, including Haverford College and Dartmouth College, in 2002.

"The US audiences told me that, although they couldn't understand the words, the rhythm of my speech and my facial expressions created what they called a 'one-person symphony'," Lian recalls.

Lian keeps the ancient art from alive by keeping up with the latest news and talks with audiences so she knows what they care about.

She sprinkles her ancient stories with modern components.

One such story goes like this: "The emperor angrily asks: 'Why haven't you found the thief yet?' The minister answers: 'I haven't got a smart phone yet. I'll find him as soon as I can access GPS."

Her apprentice Wang Yuebo performs pingshu every weekend.

Wang points out it's rare to see a folk artist performing at Lian's age.

"She always says performing pingshu is the best way to stay healthy because it requires physical and mental energy."

Wang says Lian's acclaim refutes the idea that pingshu, like many traditional Chinese art forms, is dying. "Look at the audience, and you'll see many young people," he says. "That's the future."

Today's Top News

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|