Private becomes public

Updated: 2012-02-17 13:37

By Zhu Linyong (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

|

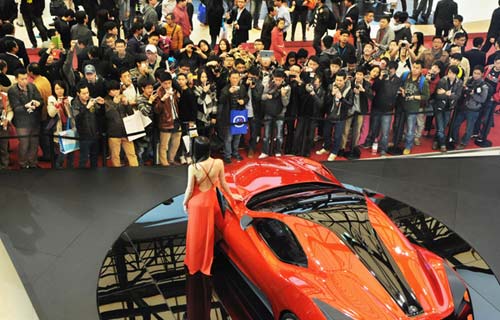

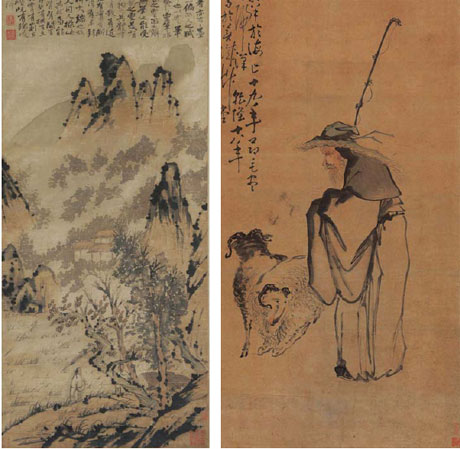

Jiang Gan Visits Friends by Shi Tao; Liu Hai Plays with a Toad by Liu Jun. |

|

|

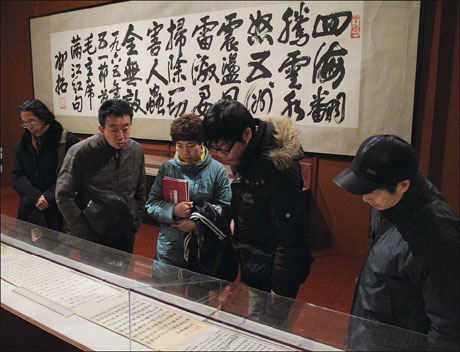

The exhibition draws a big crowd of art lovers to the National Art Museum of China. Jiang Dong / China Daily |

|

|

Deng Tuo (1912-66), a well-known historian and poet, began collecting art in the 1930s. Provided to China Daily |

An exhibition of works from a private collection in Beijing features great works from past masters. Zhu Linyong reports.

A Special Exhibition of Deng Tuo's Donations to the National Art Museum of China has drawn crowds since its opening just before the Lunar New Year. The exhibition presents for the first time more than 140 ancient ink artworks donated to the museum by Deng Tuo in 1964, from his private collection. The exhibition offers a rare artistic feast for viewers, says museum director Fan Di'an. Among the eye-catching items are masterpieces by the most-recognized artists from the Song Dynasty (960-1279) through the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), such as Su Dongpo (1037-1101), Shen Zhou (1427-1509), Zhu Da (1626-1705) and Zheng Xie (1693-1765). Arguably, the most important item on show is Su Dongpo's Bamboo and Rocks scroll. It is generally believed to be the only existing authentic work still to be found on the Chinese mainland by the versatile artist, who enjoyed fame during his lifetime due to his literature, poetry and calligraphy. With a height of 28 cm and a width of 105.6 cm, the scroll, which is featured on the third-floor exhibition hall, was created on a single piece of silk. The only other surviving painting by Su, Withered Tree and Queer Rock, is now housed in a Japanese museum and was taken during the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression (1937-45), Fan says.

Deng (1912-66) was a well-known historian, poet and former publisher and editor-in-chief of People's Daily.

He was persecuted during the "cultural revolution" (1966-76) and killed himself as a result.

Deng developed a deep love for classical arts and culture in his early years and began collecting in the 1930s, when he was fighting in the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression.

He donated his collection, most of which focused on old Beijing, to the National History Museum of China (now the National Museum of China) in the 1950s.

"To mark the 100th anniversary of Deng's birth, we are holding this special exhibition, displaying the entire collection at once for the very first time," Fan says.

Deng is "one of the outstanding official-scholars in New China, who cherished a passion for ancient art and invested much energy in building a private collection", says Liang Jiang, a researcher of ancient ink art and a key organizer of the exhibition.

However, "Deng's purpose was not to possess these works but to use them as firsthand materials for his research of ancient Chinese art history", says Beijing-based art critic Sun Wei.

"Deng was planning to write books about ancient art, including a history of ancient ink paintings. But his tragic experiences prevented this."

Deng Tuo's daughter Deng Xiaohong says: "Behind every piece there is a heart-wrenching story."

In 1964, Deng Tuo, then editor-in-chief of People's Daily, donated 145 paintings from his personal collection to the government, including Bamboo and Rocks.

In the early 1950s, an art dealer meant to sell the Bamboo and Rocks scroll to a foreign collector. Deng heard about the news and was very concerned.

"My father sold at least 14 other ancient ink paintings in his private collection to raise money to rescue the painting from the art dealer," the daughter recalls.

"I believe my father can rest in peace as the piece was later appraised as an authentic Su creation and is now considered to be one of the greatest treasures of the museum."

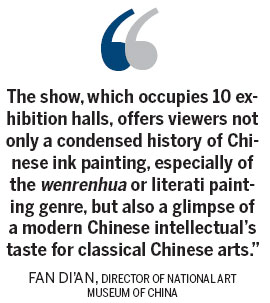

"The show, which occupies 10 exhibition halls, offers viewers not only a condensed history of Chinese ink painting, especially of the wenrenhua or literati painting genre, but also a glimpse of a modern Chinese intellectual's taste for classical Chinese arts," the museum's director Fan Di'an says.

Literati painters were greatly respected and their work was part of high culture in dynastic China, Fan explains.

The great literati painters wrote at length, advising on techniques for painting and calligraphy, forming influential schools of thinking.

Every succeeding generation of literati painters rekindled the spirit of their ancestors through their own works. The tradition continues to today and can be seen in City and Countryside: Ink Art by Contemporary Artists - another ongoing exhibition at the museum, Fan says.

Many excited visitors took photos to share their viewing experiences with friends back home or with netizens on micro blogs.

The exhibition "opens up a door to classical fine art. Previously, my main interest focused on pop singers and movie stars", says Li Wenquan, a teenager from Shandong province, who visited the exhibition.

The most important lesson he learned from the exhibition is: "We need to do some homework before seeing a classical art exhibition, just as we do before attending a classical Western music concert, ballet or opera, which is key for young people like me to nurture a refined taste for our time-honored artworks."

Liu Shijie, a retiree and volunteer guide, helps ordinary visitors gain a deeper understanding of the artworks by giving free lectures onsite.

She calls her work on the weekends "a rewarding experience". "I interact with enthusiastic audiences from different countries their questions have pushed me to learn more about these artworks and their donors."

The exhibition will run until April 10.

Today's Top News

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|