Threads of life

Updated: 2012-01-29 17:01

By Qiu Bo (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

|

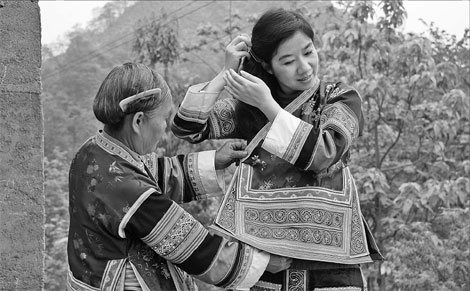

Miao embroidery expert Zeng li tries on a new costume by 63-year-old Yang Wenxiu. Zeng has visited countless Miao villages in Guizhou provice in the past decade. Provided to China Daily |

Father-and-daughter team helps keep ethnic art alive for future generations. Qiu Bo reports.

About 20 years ago, most young girls of the Miao ethnic group had difficulty reading and writing.

Many of them expressed themselves through traditional Miao embroidery stitching horsetail hair on batik and giving life to colors from abstract images.

"Because the Miao are an ethnic group without systematically written words, the girls are highly sensitive in interpreting the images," said Zeng Li, an expert on Miao culture.

"They are not simply producing handicrafts, they are a group of true artists."

Zeng was born in the 1960s in southwest China's Guizhou province, where some 4.3 million Miao people live. She has visited every single Miao village in the region in the past decade.

Miao embroidery costumes are one of the expressions of spiritual life for the ethnic group and the art has been around for four to five thousand years.

Zeng's aim to protect and develop Miao embroidery, following in the footsteps of her late father, has become her life's work.

Her father Zeng Xianyang was a local press photographer who became deeply impressed by the Miao art during his trips to the province three decades ago. He started collecting the creations himself to help them from becoming extinct.

"My father was wise and he firmly believed in preserving the art," Zeng said.

Under her father's influence, Zeng came into contact with Miao culture when she was 9. But learning about the ethnic group was just an interesting hobby outside school.

But in 2002, she started managing her father's collections and became his assistant.

"Our relationship was more like collector to collector," she said. "It's a joy to share information and feelings for the embroidery to each other and our conversations on them always took hours."

Zeng's father died in 2008 and he left her with more than 2,000 precious sets of Miao embroidery. Zeng has added another 4,000 sets to that collection through her own purchases or receiving them as gifts. Under her expert eye, each set is a rarity in itself and reflects extraordinary cultural value.

"Every set of costume has soul. I collect Miao embroidery not only for study and research, but also because I feel a stronger purpose to pursue its eternal beauty," Zeng said.

"I collect and preserve them for future Miao generations," Zeng said, adding the works are priceless and none of them will be sold.

In China's first-tier cities such as Beijing and Shanghai, Miao embroidery is sometimes sold in some open markets at thousands of yuan for each set.

The British Museum also had more than 400 sets of Miao embroidery in its collections by the year 2000.

A Miao girl normally learns Miao embroidery when she is about 7 or 8 years old. The girls generally produce their best work when they are 20 or 30.

"Making a good set of Miao embroidery will cost a woman at least two years and each girl may create up to three sets that reflect her life's work," Zeng said.

"Most of them enjoy making the embroidery without any financial incentive," she said.

Zeng once found a characteristic Miao embroidery in a remote village and wanted to buy some of it. The girl making the costumes agreed to sell her work for 2,500 yuan. But when Zeng wanted to buy more of them, the girl raised the price to 4,000 yuan.

"She said that if she had to make more of the costumes, she would lose some of the joy in producing them," Zeng said.

In revisiting the Miao villages in mountainous areas that her father went to, Zeng walked for thousands of kilometers and was warmly welcome in every Miao village.

"Many of them gave me costumes as gifts after they heard of my work."

Zeng recalled her unforgettable meeting with the 63-year-old Yang Wenxiu. The woman initially refused to wear her new costume for Zeng's picture and did so only after some thought. Yang later confessed to Zeng that the costume was made for her funeral, in line with local custom.

"I was very moved," Zeng said. "She refused to wear it not because it was not beautiful, but because it meant too much to her."

Zeng has also faced many dangerous encounters in her work.

She once drove through a slate bridge during a thunderstorm and the structure collapsed as soon as she crossed it.

"We are deeply touched by her dedication to Miao embroidery, which inspires us to work for her," said 30-year-old Wang Yang, Zeng's assistant. Other than an office and full-time team working for her, Zeng also established a Miao embroidery museum in Guiyang, Guizhou's capital, in 2007. The museum has since received thousands of visitors from all over the world.

Yang Peide, the head of Guizhou's Miao Culture Institute, said that while Zeng and her father are not from the Miao group, their efforts in promoting and passing on Miao embroidery will definitely motivate more people to join in their cause.

"They have devoted their lives to this," Yang says. "I salute them."

Today's Top News

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|