Doubts linger over warning system for smog

Updated: 2014-03-12 08:29

By Wu Wencong (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

|

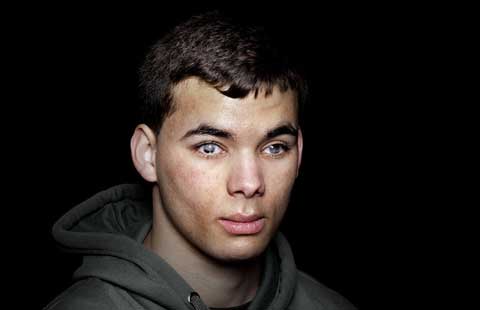

A visitor takes a photo at Tian'anmen Square on Feb 25, when Beijing issued an orange alert. [Zou Hong / China Daily] |

"Within just 10 hours, a city's AQI can rise from 30 to 300, which indicates severe airborne pollution, but the total emissions of pollutants in the region may not vary much," said Yan Jingjun, deputy head of the ministry's environmental emergency and accident investigation center.

"Measures taken during periods of high airborne pollution can usually reduce emissions by about 10 percent, a level that cannot immediately dispel the smog and allow the sun to be seen, but the measures can help slow the development of the pollution and shorten its duration," Yan said.

Comparing the long smog outbreak in February this year with the one in January 2013, which occurred at similar times of the year and mainly affected the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei cluster, the area affected in February was 900,000 sq km smaller, the outbreak was four days shorter, and even the highest daily AQI for most of the affected cities was much lower, according to figures from the Environmental Protection Ministry.

However, by January 2013, no Chinese city had formulated emergency measures to deal with airborne pollution. Beijing, the first place to produce a plan, did not issue it until late October. Now, 38 cities across China have produced emergency plans.

"Thanks to the issuing of nationwide alerts, many local governments had time to take advance measures to tackle pollution during the smog outbreak in February," said Yan. "That's why the level of pollution was much lower than during the smoggy period a year or so ago."

Environmental experts said emergency plans to deal with short-term pollution may help improve the annual average air quality.

"Research shows that the 11-day blanket of smog that covered 2.7 million sq km in January 2013 alone resulted in an increase in Beijing's PM2.5 concentration for that year by 5 micrograms per cubic meter," said Chai Fahe, deputy head of the Chinese Research Academy of Environmental Sciences.

The monthly average concentration of PM2.5 - particles smaller than 2.5 microns in diameter which can penetrate deep into the lungs and even enter the bloodstream - for Beijing was more than 140 mcg per cu m in January 2013. If emergency measures had resulted in the concentration falling to around 130 mcg per cu m, then the capital's annual average PM2.5 level for 2013 would have fallen to 87.5 mcg per cu m rather than the current 89.5, according to He Kebin, a professor at the Environmental School at Tsinghua University.

"Although emergency measures tend to treat the symptoms rather than the causes of pollution, they can still promote a process to cure the problem," He said, adding that the experience the authorities gain when formulating emergency measures can help over the long term. Meanwhile, the measures themselves, such as the enforced reduction of emissions, can also prompt businesses to upgrade their technologies and equipment because companies that use outdated technology that results in high emission levels are more likely to find their activities restricted during periods of heavy pollution.

In October 2013, Harbin, in the northeastern province of Heilongjiang, became the first city in China to suspend classes, leading to schools being closed for two days. The pollution was so severe that the highest hourly PM2.5 concentration reached 1,700 mcg per cu m. Chai, who was conducting research in the city at the time, said the closure of schools was necessary to safeguard the health of the students.

Today's Top News

Malaysia tracked missing jet to west coast

China confident of nuke safety

Vietnam widens search near Strait of Malacca

Xi vows no compromise on national interests

Crimea declares independence

Strike collapses at S China IBM

China goes all-out to search for lost jet

Renminbi is 'top priority' for London's Lord Mayor

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|