Weihsien: Life and death in the shadow of the Empire of the Sun

Updated: 2014-02-20 09:21

By He Na and Ju Chuanjiang in Weifang, Shandong province (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

"We were there as a family and lived in a small room with no sanitary facilities. I have many memories of the camp, such as being counted by the Japanese three times a day, attending school, being hungry most of the time. I was 6, but still had to work. My job was that of a bell ringer, waking people for the first roll call. The latrines were awful because we moved from flush toilets to 'squatters'," Pearson recalled.

"We very seldom had meat, and when we did it was often rotten. We had a lot of eggplants, to the extent that afterward I could not eat eggplant until I was in my 30s. As children we still had school, but the teenagers also had jobs. My older brother worked as a cobbler," he said. "Coffee and tea was reused, over and over. We arrived in late fall, around October, so our living quarters were very cold."

Pearson remembered that the adults made young children eat powdered eggshells to prevent rickets. "They got eggs on the black market and the shells had to be saved and powdered. There's nothing worse than eating a spoonful of powdered eggshell," he said.

British writer Norman Cliff was 18 when he entered the camp. In his memoirs, he said that every effort was spent acquiring fuel, food and clothing.

"The fortunes of war produced some strange situations," he wrote. "One fine British Jewish millionaire could be seen working regularly through a pile of ashes behind the kitchen, and a leading female socialite could be seen chopping wood. Our bodies were tired from long hours of manual labor. We often went to bed longing for more food. Two slices of bread and thin soup were hardly a satisfying supper after a day spent pumping water and arraying heavy crates of food."

Loss of dignity

Some people have called Weihsien camp "the Oriental Auschwitz".

"Because of the poor sanitary conditions and the shortages of food and medical care, several people died in the camp. But still I don't agree with calling it 'Auschwitz' because there was no slaughter there. That's the truth. Japan mainly wanted to humiliate the allied countries," said Xia Baoshu, 82, a Weihsien camp researcher and former president of Weifang People's Hospital.

Mary Taylor Previte, 81, who later served in the New Jersey General Assembly, was interned at the age of 9.

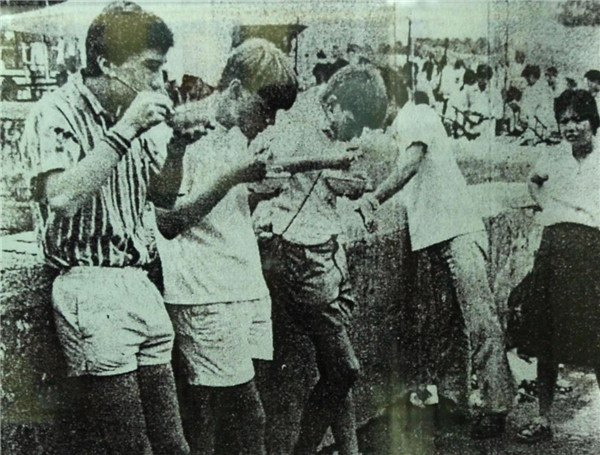

"The second day after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Japanese soldiers appeared on the doorstep of our school. They said we were now prisoners of the Japanese. I remember so well when the Japanese came and marched the school away - perhaps 200 teachers, children and old people - to the concentration camp. I will never forget that day. A long, snaking line of children marching into the unknown, singing a song of hope from the Bible," she said.

"Separated from our parents, we found ourselves crammed into a world of gut-wrenching hunger, guard dogs, bayonet drills, prison numbers and badges, daily roll calls, bed bugs, flies and unspeakable sanitation."

Related Stories

CNN remarks over WWII memorial spark outrage 2014-02-07 21:45

WWII Flying Tigers want to see history respected 2014-02-07 13:23

Suspected WWII bomb found in HK island 2014-02-07 07:11

Japanese cruelty in WWII nothing to sweep under carpet 2014-01-30 11:13

Japan should learn from Germany: WWII survivor says 2014-01-28 11:13

WWII sites dwindle 2013-11-08 10:48

Today's Top News

Ukraine sets back on European course

Chinese pandas arrive in Belgium

Brit master teaches Chinese Tai chi

Think tank examines South China Sea

Europeans nervous over China deals

Beijing upgrades haze alert

China urges US to correct mistakes on Tibet

9 punished for spreading flu rumor

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|