Sailors wait for tide of danger to pass

Updated: 2011-10-25 07:34

By Cui Haipei (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

Mekong murders suspend river trade, Cui Haipei reports from Xishuangbanna, Yunnan province.

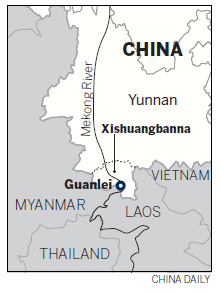

Mist rises from the water at Guanlei Port in Xishuangbanna and wafts past about 20 cargo vessels neatly docked in the tropical sun. The port, the first in China for boats sailing upstream on the Mekong River, is shrouded in uncommon silence.

On Oct 5 two Chinese boats based in Guanlei - Huaping and Yuxing 8 - were attacked in northern Thailand by an armed gang. Both captains and 11 sailors were murdered, the full complement of both vessels. All had been shot with their hands tied behind their backs.

Since the attack the Yunnan government has not allowed Chinese boats to leave the port for the Mekong. Freighters have turned to road transport which costs four to five times more than waterways. In contrast to Guanlei Port, hundreds of trucks line up to go through customs at Mohan on the China-Laos border.

The boats docked at Guanlei are tended by only captains and a few sailors. More than 1,000 Chinese sailors make their living on the Mekong, but about two-thirds have been given permission to go home, Wu Dechang, captain of the Zhongsheng, said. He smokes cigarettes through a water pipe during the long hours aboard his boat in the harbor.

"We now have no income," he said. "We hope the governments can thoroughly investigate the attack in two or three months and give us a sense of security. Only when that happens can sailors return to the river."

The area where the attack occurred is known for drug trafficking, and Wu said robbery has become increasingly frequent on the Mekong in the past two years. Armed robbers usually drive speedboats and wear camouflage clothes, and some sailors have reported seeing a rocket launcher on their shoulders. The cargo boats always stop as ordered, Wu said.

Most times, the robbers fire shots into the air and snatch watches, wallets and whatever other valuables they see, Wu said. The Oct 5 attack was the first in which lives, not assets, were taken.

A family tradition

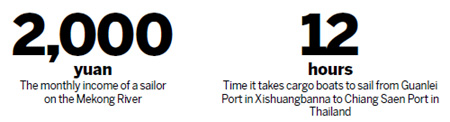

Wu has been sailing the Mekong River for 18 years, since he was 20. It has provided a livelihood for Chinese sailors, most 18 to about 40 years old, since the 1990s. They earn about 2,000 yuan ($303) a month when they are on the river.

The sailors are mainly from the mountains in Southwest China's Sichuan, Guizhou and Yunnan provinces. For many of them, it is becoming tradition in their villages for young men to leave and become sailors. Wu, from Hubei province, succeeded his father in becoming a sailor and then a captain on the Mekong River.

His boat was supposed to have sailed with Yuxing 8, but its loading equipment broke down, so the Huaping took its place at the last minute. Huaping was loaded with 260 tons of fruit. Yuxing 8 sailed empty, but was to have delivered diesel fuel from Thailand to Myanmar on the return trip.

"It could have been me and my crew who died," Wu said. He was the first to release news of the attack when he posted it on the online forum Tianya.cn on Oct 7.

Uncertain future

Wang Guichao, at 45 the chief engineer of Yuxing 8, was one of the 13 Chinese confirmed dead in the attack. Along with other victims' families, his wife and two children are staying at the Youxiang Hotel in Jinghong, capital of Xishuangbanna Dai autonomous prefecture.

They arrived Oct 14 from Thailand, where they provided DNA samples so the bodies could be identified and where a memorial service was held. Now the families are waiting for Chinese and Thai police to complete their investigation.

Wang came from a mountainous village called Heping (which means Peace) in Suijiang county, Zhaotong, Yunnan, which is more than 1,000 kilometers from Jinghong. He had worked on the river since 1992, made 50,000 yuan a year, and was the main breadwinner for a family of six, including a 23-year-old son in college and an 80-year-old mother who has still not been informed of his death.

"When I heard my husband died, the whole world seemed to fall apart and my body became numb. What shall our family do in the future?" said Wang's wife, Yang Duoxu.

Two months earlier, she had started working as cook on another cargo vessel, Guangyi, earning 1,000 yuan a month. "We intended to stay here for another year or two till our son graduates from college, but never thought such a thing could happen.

"Now I cannot fall asleep until 2 or 3 at night, expecting him to tell me something, but I always wake up suddenly, and it is still dark," Yang said, crying.

She said Wang had not paid for life insurance and the family had not received any compensation, so there is much uncertainty for this family. She did farming work before joining her husband on the river, and her family owns a little cropland, so she might return to that life, she said. But she really has no idea what is to come.

The village of Heping lost three other men the same day, all from the Yuxing 8: Yang Zhiwei, an 18-year-old sailor, did not buy insurance either. His father, Yang Deyi, was the captain and had been missing, but police announced that his body was recovered on Sunday. His uncle Wen Daihong died, too.

Speed and cost

Despite safety concerns, the strategic and economic role of the Mekong is undeniable. Guanlei faces Myanmar on the east side of the river and borders Laos by land in the south.

China, Laos, Myanmar and Thailand signed a free navigation agreement for the Lancang-Mekong River 10 years ago. The Mekong is known as the Lancang in China. It rises on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and flows through China, Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam before emptying into the South China Sea.

From Guanlei Port, it takes only 12 hours for cargo boats to sail to Chiang Saen Port in Thailand. The return journey upstream takes about 20 hours.

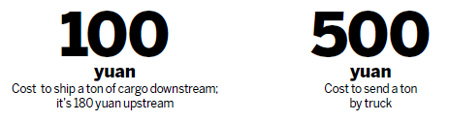

A ton of cargo costs 100 yuan to ship downstream and 180 yuan upstream. Sending a ton by truck costs 500 yuan each way and takes twice the time.

According to the Yunnan waterway administration authority, 98 Chinese cargo vessels sail annually on the Mekong, carrying about 400,000 tons of goods. Load capacity ranges from 190 tons to 380 tons. How fully they are loaded depends largely on the water volume in the river, which runs fullest from August through November. On average, the boats make 15 round trips each year, not fully loaded every time.

From 2000 to 2009, China delivered more than 3 million tons of cargo through the river, and the total value of imports and exports has surpassed 30 billion yuan.

|

Work at a standstill

After the Oct 5 attack, the provincial government suspended Chinese shipping on the river. Moreover, an attack on 18 Chinese tourists on the Mekong in August forced Chinese tourism companies to suspend operations in the area. This old golden waterway appears deserted.

"After the suspension, the shippers have to choose overland delivery to Thailand through Myanmar and Laos, spending four to five times what they paid before," said Fang Youguo, secretary-general of the Lancang River Shipping Association. Usually, freight traffic peaks each year from August to the next Spring Festival, "but now it is almost at a standstill," Fang said.

Business on the Lancang River had been booming since last Spring Festival. It handled 210,000 tons of cargo in the past nine months, about 20 percent more than in the same period last year, said Duan Jinhua, a senior publicity official for the Xishuangbanna prefecture.

Now, when other boats arrive back at Guanlei Port, docking has become a problem, Fang said. Regulations allow no more than four boats to tie up side by side at any one berth, and the port is close to capacity, if spare of crew.

"A sailor has just left, and I guess he quit this business," said Wu Dechang, the captain. "In such a situation, who else dares to run a ship again along the river?"

Meanwhile, expenses are mounting, Wu said. It costs about 30 yuan a day in docking fees, the crew of seven is paid 12,000 yuan in total each month, and the Zhongsheng is generating no revenue.

Guanlei town and its nearly 3,000 residents are feeling the effects as well. Shipping has been its primary industry.

Wen Shugui, who came from Sichuan province, runs a 40-room hotel that is the largest in the town. "Guanlei has 20 hotels of all sizes," he said. "In the past, at least half of my rooms would be filled, but everything has changed since the suspension."

Hotels and many of the stores in town will close if the suspension lasts a long time, Wen said.

Generation's duty

Permanent changes in freight transportation through the Mekong River region are on the horizon, though they aren't imminent. A railway network connecting countries in Southeast Asia will make trains an option for delivering goods as well as people.

A line connecting Yunnan's capital, Kunming, with Thailand's capital, Bangkok, is under construction. Tracks have been laid in Mohan Port on the China-Laos border, and building of a logistics center started last December. Part of the railway has been completed and the entire line is targeted to open in 2015.

Wu Dechang is familiar with the hazards along the Mekong - he is captain of one of the only three Chinese boats that have not been robbed - but he is convinced that water delivery will not disappear.

"First, with development of the economy, demand for freight services will certainly grow and so will our shipping services," he said. "Second, though the scale of shipping is relatively smaller, our operating mode is convenient and flexible. Third, taking factors of labor and transport turnovers into consideration, actually the two modes (ship and rail) cost a similar amount."

Wu said he will return to sailing on the Mekong River. "I am the second generation on the golden river. The route was developed by our parents' generation, and if we ruined it, how could we face our descendants? How would they think of us?"