On this beach no one is naked

Updated: 2014-10-03 07:27

By Zheng Yangpeng and Yuan Hui(China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||||

Inner mongolia's Solar firms bask in sunshine of fine-weather days and growing orders

For many in China's photovoltaic industry, the solar products trade war between China and Europe is a distant memory. As domestic demand has continued to grow and new markets such as Japan have emerged, the industry finally seems to be back on track.

In Jinqiao Industrial Park in south Hohhot of Inner Mongolia autonomous region, few signs remain of the storm that hit this center for manufacturing polysilicon and monocrystalline, a sector sensitive to down-stream industries such as solar panels.

|

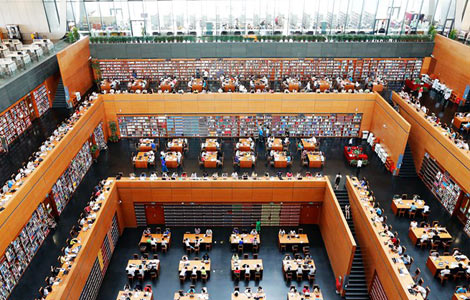

Workers at the factory of Inner Mongolia Zhonghuan Solar Material Co in Jinqiao Industrial Park in Hohhot. Provided to China Daily |

The facades of one of the factories here could not be any more bland or its surroundings any quieter, but once you get inside you find high-tech machines humming away as a few white-garbed workers shuttle between them.

One of the companies in the park is Inner Mongolia Zhonghuan Solar Material Co, whose managers say that even in 2011 and 2012, when weak foreign demand pushed stockpiles to a record high as Europe undertook anti-dumping and anti-subsidy investigations, the company kept up production.

The company, a subsidiary of Tianjin Zhonghuan Semiconductor Co, makes monocrystalline silicon, a key element in solar cells.

Several years ago when the tide rose on China's PV industry, seeming to promise endless growth, local governments and companies were enthusiastic investors. Then came the 2008 financial crisis, and everything changed, with overcapacity and bad debt becoming industry bywords.

Pan Xiujian, deputy general manager of Zhonghuan Energy, another subsidiary of Tianjin Zhonghuan, who has worked in Zhonghuan Solar, recalls the boom years fondly.

In 2006 and 2007 short supply meant customers had to have a lot of cash on hand because they paid manufacturers before orders were delivered. Quality seemed to be of little concern to the customers, the main thing being that they could get their hands on products.

"Business people who had been in luggage bag and shoe manufacturing flocked into the industry, lured by the promising outlook," Pan says. "But most of them fell away when demand plunged in 2011 and 2012."

As the tide ebbed, it became clear who was, in Warren Buffett's words about another set of investors, "swimming naked".

"The problem with China's PV industry is that few companies have core competitiveness, which is what keeps you from being copied by other people," says Steven White, associate professor in the department of innovation, entrepreneurship and strategy of Tsinghua University in Beijing.

Zhonghuan Solar is an exception. Its parent, Tianjin Zhonghuan, a state-owned company, has worked in semiconductor materials since 1958 and solar batteries since 1988. With strong know-how in monocrystalline silicon manufacturing and wafer processing, it was able to withstand the winds that buffeted the industry. In 2007 it was listed on the Shenzhen Stock Exchange.

In 2009, with the industry still ailing following the global financial crisis, Tianjin opened its monocrystalline silicon factory in Hohhot.

"Of course, as the industry suffered, we were not immune," Pan says. "But we did everything to reduce production costs and improve efficiency through lean management."

Through a glass screen in the factory, a few workers can be seen operating a forest of mono-crystal furnaces. Managers say that when the factory opened, one worker took care of three to four furnaces. Now one can operate 12 simultaneously, thanks to automation.

The company says that as a result of that and other efficiency improvements it was able to raise salaries in 2011 and 2012.

The factory has also benefited from a low power tariff, of 0.47 yuan ($0.0766; 0.06 euros) a kilowatt hour, which is one of the main reasons the company decided to locate the factory in the city. By comparison, the tariff for industrial electricity in Tianjin is between 0.8 and 0.9 yuan a kW/h, and the price can exceed 1 yuan a kW/h in coastal regions such as Zhejiang and Fujian.

"Of course, other regions have favorable tariffs, too," Pan says. "The difference is that businesses get favorable pricing through subsidies. But governments cannot afford these if huge amounts of power are being used. Here we don't need such subsidies."

The company is now focused on developing monocrystalline silicon, believing solar cells made of that will overtake those made of polysilicon, which at the moment account for a larger share of solar cells sold in China.

In the industry generally the focus has switched from reducing required investment per watt of electricity to lowering production costs per kW/h, Pan says, and in this regard monocrystalline silicon-made cells have an advantage.

Tianjin Zhonghuan is also seeking to expand its activities in Inner Mongolia to power generation. With SunPower Corporation, a US company that has expertise in high-efficiency solar cells, Zhonghuan was able to produce SunPower's proprietary C7 solar cell receivers, which will be installed in PV stations that enable a conversion rate of 25 percent or more, the highest in the world.

Huaxia Concentrated Photovoltaic Power, a joint venture between Zhonghuan, SunPower and local companies, has been given the green light to build a 20 megawatt solar farm in Hohhot and a 100 mW one in a neighboring county, both of which are expected to be completed next year.

The farms will use third-generation technology that reflects light onto solar cell receivers, concentrating the sun's energy seven-fold.

Exports still account for 70 percent of Zhonghuan's sales, but its export destination countries have changed, once dominant Europe having been replaced by South Korea, the Philippines and Malaysia.

Another major company in the Jinqiao zone, Orisi Silicon Co, produces mainly polysilicon that it only sells in China. The company is a subsidiary of China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation, a state-owned conglomerate, and Orisi also sells its products to other China Aerospace offshoots.

"A score of customers buy up what we produce," says Ma Jiangong, a manager with Orisi. "In the first eight months of this year our sales grew 76 percent compared with the corresponding period last year."

The domestic market has lost some of its significance as fewer PV units have been installed, putting a dampener on the price of polysilicon. Ma says that despite rapid first-half growth he is pessimistic.

He has called for central and regional governments to step up support for enterprises' technology innovation in an effort to drive down production costs.

Zhonghuan and Orisis epitomize the PV industrial cluster gradually taking shape in Hohhot. The city, an emerging economic hub on the Mongolian plateau, is creating an industrial chain that promises to reduce the city's traditional reliance on the petrochemical industry.

From the PV industry's upper stream, the production of polysilicon and monocrystalline silicon, to the middle stream, solar panels, and to the down stream, solar farms, four big enterprises in the city have invested in each field. The city is building another industrial park for other enterprises.

The city now has annual capacity of 5,000 metric tons of polysilicon, 10,000 tons of monocrystalline, 30 mW of solar cells and modules, the city authority says.

Wang Jianguo, deputy director of the Saihan district of Hohhot, where Zhonghuan Solar is located, says that compared with the petrochemical industry, which contributes more than 30 billion yuan worth of added-value a year, the PV industry is still small. But its rapid growth, fast-evolving technology and promising future are unrivalled.

"We are particularly interested in the conglomeration effect," Wang says. "As big companies come here, that will attract many more."

With low power prices, and abundant solar resources and premium silicon ore, Inner Mongolia is well suited to further growth in the solar industry, he says.

However, the Hohhot city authority acknowledges that the industrial cluster, concentrated on the upper stream at the moment, is yet to mature. Compared with companies dealing in solar panels and modules, upper-stream firms have much less influence on pricing and sales channels and are poor at drawing on the resources of the whole industrial chain. The next step is to use the city's advantages to lure more enterprises, especially private ones.

zhengyangpeng@chinadaily.com.cn

)

Today's Top News

Barrage of deals expected on Europe trip

First US Ebola patient dies

Sino-Portuguese relations make 'giant leap' forward

Holiday spending habits change

Book of Chinese president debuts at Frankfurt fair

China's 'Nightingale' races for Oscar

Britain to deploy 750 servicemen in West Africa to tackle Ebola

Hopes high for Premier Li's visit to Germany

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|