All in a day's work: Falling boulders and floating dust

Updated: 2011-12-07 10:46

By Wang Kaihao (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

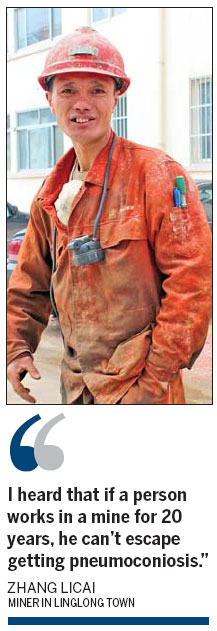

Gold miner Zhang Licai recalls hauling his bleeding colleague aboveground in 2004.

The man had worn his standard-issue helmet and back brace, as tumbling rocks are common in the mineshafts.

"(But) his helmet shattered into pieces," the 44-year-old native of Jiamusi, Heilongjiang province, recalls.

"My clothes were drenched in blood by the time I had carried him to the surface. His death still haunts me when I can't sleep."

|

Such accidents are never far from the minds of Linglong town residents in Shandong province's Zhaoyuan city, which sits above a honeycomb of tunnels dug by miners burrowing for gold for nearly half a century.

Linglong miner Zhang Quanyou says he'll never forget watching his friend die two years ago.

"I'd just finished my shift and was waiting for my buddy to ride the cage (elevator) to the surface with me," he recalls.

"I lit a cigarette. That instant, a boulder crashed on him. I was too astonished to say a word."

The 24-year-old wouldn't return underground for more than a month afterward. He still sometimes refuses to go down if he gets a bad feeling.

Safety problems are greater at private mines, says Zhang Licai, who worked for private mines for five years until he took a job as a driller at a State-owned operation in Linglong in 2006.

"Private mines don't have safety training or rigid supervision," he says.

However, Zhang Licai says he earned twice as much as his current monthly pay of 5,000 yuan ($773) in private operations.

But private mines also run on erratic schedules so salaries are often irregular.

"If the boss runs out of dynamite, we wouldn't work and wouldn't get paid for several days," Zhang Licai says. "Other days, I'd have to work for 12 hours underground. Every time I return home now, I'm relieved because I have money in my pocket."

Some private operations don't prospect before mining. They randomly dig and relocate if nothing is found for several days, Zhang Licai says.

Mine manager Qian Jun says safety meetings are held before every shift.

"It's more like a chat," he says.

"If a miner has recently had an argument, or is drunk or depressed, he doesn't go down. It's very dangerous if he can't concentrate."

Qian's mine also employs full-time safety officers, who start their days by clearing out loose rock.

Zhang Licai says, "The vast majority of accidents can be avoided if we're careful enough."

Every miner has a GPS and an emergency-call device that allows them to instantly inform their supervisors of accidents.

But perhaps the greatest dangers gold miners face comes not from falling boulders but rather from floating dust.

Years of breathing the particulates created by drilling and explosions can cause the potentially fatal lung disease, pneumoconiosis.

Last year, 256 people were diagnosed with the disease in Yantai city, which contains Zhaoyuan, the local portal website Shuimu.com reports.

However, the number doesn't account for the many miners at private operations, whose lack of legal contracts leaves them without occupational disease appraisal channels.

Pneumoconiosis accounts for about 90 percent of the country's occupational disease cases. More than 670,000 had the disease nationwide at the end of 2010, the Ministry of Health reports.

Miners at Linglong's State-run mine receive checkups every three months and must retire if diagnosed with pneumoconiosis.

Retired miner Cui Jianmin says Linglong mine ended about 300 meters underground decades ago. But some shafts now plummet more than 1,700 meters belowground, where ventilation is worse, the 68-year-old says.

Authorities have installed machines to improve ventilation and a water-spray system to eliminate dust.

But Zhang Licai still plans to quit in five years, for fear of his health.

"I heard that if a person works in a mine for 20 years, he can't escape getting pneumoconiosis," he says.

"So I'll earn a living another way after I've saved enough for my 19-year-old son to get married."

However, he recalls he failed when he tried to sell corn for two months.

"I don't know exactly what I'll do," he says.