The warrior prince

Updated: 2011-11-04 07:59

By Han Bingbin (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

|

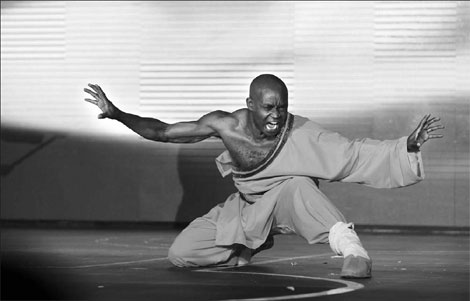

Dominique Saatenang, who studied at Shaolin Temple, aims to spread kungfu culture. [Wang Jing / China Daily] |

A Cameroonian tribal king's son swaps his royal robe for that of a Chinese kungfu fighter. Han Bingbin talks to Dominique Saatenang.

Dominique Saatenang's journey spans not only continents but also identities.

The Cameroonian tribal prince swapped his royal robes for those of a Shaolin Temple monk and traded in the ceremonial spear of an African ruler for the sword of a Taoist martial artist.

And while he has forsaken his ascension as a king in his homeland, he has risen to become chairman of the French Africa Wushu Association (AFA WUSHU) and Association Kungfu Wushu du Cameroun. His mission, he says, is to train international "ambassadors of kungfu".

Saatenang left the successful company he had founded in Cameroon to come to Shaolin. While training at a school near the temple, he broke through a security line to shake hands with the abbot, Shi Yongxin.

The abbot surprised Saatenang when he brought the foreigner to the front of the line, gave him a name card and told him, "Find me again when you have time".

Saatenang was so excited that he registered at the temple the same day. A month later, he started what Shaolin's liason Wang Yumin describes as four "diligent and painstaking" years of studying martial arts and Buddhism.

That wasn't the first time the kungfu enthusiast had taken drastic action for his love of martial arts.

When he was 11, he told his father he would quit school if he couldn't practice kungfu rather than soccer, which he excelled at and his father hoped could offer him a brighter future.

The boy became determined to master kungfu after watching Bruce Lee's Enter the Dragon.

"I'd found what I really needed in life," he says.

His father told him, "Everybody in China knows kungfu, but they still don't have any money."

After overcoming his father's objections, Saatenang faced another problem - there weren't any kungfu practitioners, let alone instructors, in Cameroon. His first teacher was actually a taekwondo coach, who had picked up kungfu moves from movies.

So Saatenang learned vicariously for six years, until he one day chanced upon a Chinese man practicing taichi in a park.

The Cameroonian couldn't speak any Chinese, but used every gesture he could think of - while shouting "Kungfu! Kungfu!" - to persuade the man to accept him as an apprentice.

The man smiled and wrote "5:30" on the ground.

That was the time the two met every morning for the next three years. Because they couldn't speak to each other, the lessons relied on body language.

Saatenang recalls trying to pay the man, who turned out to be an international volunteer, when the Chinese left Cameroon three years later.

He would only take a few small coins as souvenirs, Saatenang recalls.

Saatenang soon after met a Chinese doctor living in Cameroon, who also knew kungfu. They co-founded a martial arts association in Gabon.

Saatenang began traveling throughout the country to organize kungfu performances and training courses.

But he felt his dream couldn't be fully realized until he visited Shaolin, the most venerated place to Chinese martial arts, which he had learned about from Jet Li's 1982 film that shares the temple's namesake.

He made the pilgrimage to Henan province in 2000, at age 25.

During his stay in China, he returned home twice a year to keep tabs on the company he had founded, which supported his family after his father passed away in 1997.

He enrolled in a two-year course on contemporary martial arts at Beijing Sports University in 2005, after discovering traditionally trained fighters encountered difficulties entering international contests.

Saatenang started snapping up international competition awards, including the 2006 Hong Kong International Wushu Festival's top sword play prize.

He then moved to France and founded AFA WUSHU.

His organizations have more than 3,000 members and disciples. Saatenang is cooperating with the governments of five African countries to send two university students from each country to study at Shaolin Temple for free for five years.

The students will be trained in kungfu and sports medicine in the longest lasting and most comprehensive program the temple has offered for foreigners, Wang Yumin says. Foreign students previously stayed three weeks to one year, at most.

Six students have already arrived from Cameroon, Gabon and Rwanda.

Saatenang says he evaluates candidates on their motivations rather than their physical abilities. He hopes they will promote the Chinese martial art in their homelands, he says.

"If Chinese come to Africa to teach people kungfu, Africans might mistake their actions for cultural propaganda," he says.

"But it's easier for local people to accept an African teaching them."

To this end, he hopes to appear in a martial arts movie and has already finished acting classes at the Laboratoire de L'acteur in Paris.

"I just want to let people know it's not just Chinese people who can make kungfu movies," he says.

"Foreigners who study it can also do it."