View

My motherland, right or wrong?

Updated: 2011-01-28 08:05

By Raymond Zhou (China Daily)

|

Piano prodigy Lang Lang rides high on a cross-Pacific career where both music lovers and officials flock to his performances. Jiang Dong / China Daily |

|

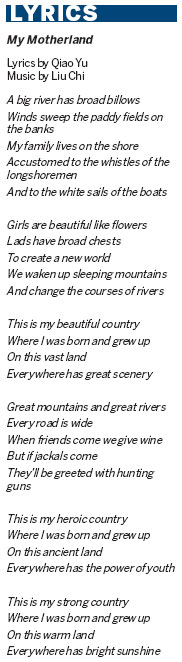

A scene from the movie Shangganling, which depicts Chinese soldiers holding out in a cave against a vast American army. Provided to China Daily |

Lang Lang's choice of music for a state dinner in the US was both lauded and chided, although it has evolved to be another folk song about love of country.

Depending on your view, pianist Lang Lang either pulled off a sucker punch or committed a diplomatic faux pas last week. He played a tune from a movie that has anti-American subject matter at the Jan 19 state banquet US President Barack Obama gave to the visiting Chinese President Hu Jintao. Even though it did not evolve into a diplomatic skirmish, it created some hoopla on both sides of the Pacific Ocean.

I believe Lang Lang when he explained afterwards he did not know the origin of this song. Its popularity has far outstripped the movie itself. While everyone in the Chinese mainland can hum it, relatively few have seen the movie or can immediately connect the "jackals" in the lyrics with the American soldiers fighting in the Korean War, or what we in China call the War to Resist US Aggression and Aid Korea.

The movie Shangganling, released in 1956, experienced a surge in popularity during the post-"cultural revolution" (1966-76) years. People of my generation are familiar with the plot, a typical war picture, but the song comes at a telling moment, a hiatus in the battle when the soldiers are reminded of the beauty of the motherland, while a few lines refer to "greeting jackals with hunting rifles".

By Chinese standards the song is quite apolitical and lacks the propaganda vibe of the time. Rendered by the most popular folk singer of the day, the beautiful Guo Lanying, it was an instant hit and has since become a classic.

As a student, before the bass singer Tian Haojiang became famous at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, he used to moonlight as a piano player at restaurants. One night a Chinese busboy requested he play the song and afterwards broke down in tears, because he was so homesick.

It is quite possible Lang Lang was attracted to the melody and oblivious to the hidden meaning of the lyrics.

However, he is now in a quandary. After I tweeted the incident on my Sina Weibo micro blog, I was overwhelmed with responses, which neatly belonged to two camps: One lauded him for jabbing the Americans with the subliminal message of contempt or enmity; while the other criticized him for making an inappropriate choice. After his explanation, the first group naturally stopped seeing him as a hero.

|

The politicization of Lang Lang's golden oldie reflects more on the mentality of some Chinese, who are accustomed to expressing themselves indirectly. If you want to criticize someone but cannot do it openly, you may have to resort to overtones, undertones and various figures of speech. Chinese literary critics and historians have made it an art to pick apart ancient masterpieces and decipher whatever codes may be embedded in them. For these people, there is no coincidence or over-interpretation. Every little gesture must be deliberate and conveys something deeper.

As President Hu's trip was one of goodwill, the last thing the Chinese government wanted, I would figure, was a reminder of past hostilities between the two countries. Had whoever who vetted the performance list known the history of the number, it may not have made the cut. But there is no guarantee that those who do the vetting are armed with such encyclopedic knowledge. In this country, we have produced a cornucopia of tales of black humor from such ignorance.

|

Sometimes, ignorance is good for broadening the appeal of popular songs.

The Chinese national anthem is a militant marching song. But who knows it is from a 1935 Shanghai-produced film. Almost all movies from the 1930s provided direct or indirect references to the Japanese invasion of China's northeast that started in 1931. But now, the cause people died for in the lyrics, has become an abstract.

It is easy to paint certain songs with the colors you want and push them one way or another. Many of the "Old Shanghai" ditties were banned in New China because they were taken to be unpatriotic. The thinking went, how can you pine for your lover and be tender while living in an occupied land? The sin is even greater when ballads like When Will My Man Be Back Again? seem to take the position of a saloon entertainer who could have Japanese among her clients. As a result, even the composer of the melody was persecuted.

Every song has a back-story. The beauty of the popular ones is, they capture a mood or emotion that cuts across a large swath of the public and transcends the time and the occasion. The theme song from the television adaptation of Outlaws of the Marsh is ostensibly about Chinese Robin Hoods who lived 1,000 years ago, but the lyrics strike home today, when there is a widening rich-poor gap.

Had My Motherland, Lang Lang's song in question, contained words such as "US aggression" or "helping out Koreans", it may not have lasted, but would instead have been confined to one war film. Because the lyrics are less obvious they have resonated with successive generations, even those who know little about the history that created it.

It is for the same reason that many Chinese musicians pick folk tunes for international performances. Folk songs, by and large, have two topics: love and homeland. They transcend all boundaries and are never controversial.

My personal favorite post-1949 patriotic number is I Love You, China, also from a movie - the 1979 Hearts for the Motherland, starring Joan Chen. It was inspired by a true story, an overseas Chinese girl who returns to China, survives political upheavals and becomes an opera singer. The song is structured like an opera aria and was sung by a classically trained singer in the film - and has been ever since. It depicts various natural scenes from across the country. And it does not have an enemy in the lyrics.

As a side note, life has more twists than art: The singer, whose life the movie is based on, left China for New York shortly after the movie was released. She recently returned, when her career in the US petered out.

I bet I Love You, China will be in the repertory of every Chinese soprano no matter what happens. Maybe Lang Lang should have chosen this one as the melody is equally beautiful.

E-paper

Ear We Go

China and the world set to embrace the merciful, peaceful year of rabbit

Carrefour finds the going tough in China

Maid to Order

Striking the right balance

Specials

Mysteries written in blood

Historical records and Caucasian features of locals suggest link with Roman Empire.

Winning Charm

Coastal Yantai banks on little things that matter to grow

New rules to hit property market

The State Council launched a new round of measures to rein in property prices.