Mysteries written in blood

Updated: 2011-02-11 11:42

By Wang Ru (China Daily European Weekly)

|

|

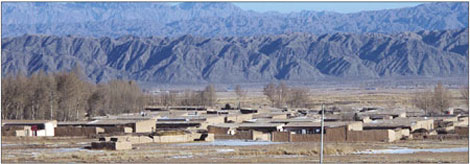

Liqian village in Gansu province is believed to be the former settlement of defeated Roman soldiers. Photos by Jiang Dong / China Daily |

Historical records and Caucasian features of locals suggest link with Roman Empire

Liqian is a village of fewer than 100 households in Northwest China's Gansu province with a link to the Roman empire. The remote village on the edge of the Gobi Desert captured international attention in the 1980s when media became aware there was something unexplainable about some residents - physiognomies. Some of the mostly Han inhabitants of the Yongchang county settlement were born with wavy blond hair, hooked noses, and blue or green eyes - in other words, European features.

Locals were at a loss as to why. They were shocked when media discovered their ancestral links could be traced back to soldiers from the Roman empire. None of the local people - who live in earthen houses, raise sheep, water potatoes and carrots, with water from the snow-capped Qilian Mountains - had ever tasted pizza or even heard of the Roman empire.

In 53 BC, a Roman legion that had been part of the army under the command of general Marcus Licinius Crassus was defeated in a battle against Parthia, an empire occupying what is now Iran. Crassus was killed, but an army of more than 6,000 Roman soldiers disappeared.

Some historians believed they were captured. Others speculated they came under the command of Crassus' eldest son and were lost in the East.

In 1941, Homer H. Dubs, a pioneering American Sinologist and polymath who was raised in China as the son of missionaries, published the article "An Ancient Military Contact Between Romans and Chinese" in the American Journal of Philology.

Dubs, who later became Oxford University's chair of Chinese, published "A Roman City in Ancient China" in 1957. This was largely recognized as the theory's origin. By compiling the historical records, Dubs speculated Roman soldiers had settled in a village in Northwest China.

Before Marco Polo's 13th-century travels to China, the only known contact between the two empires was a visit by Roman diplomats in AD 166.

Inspired by Dubs' research, Australian scholar David Harris proposed that a Gansu village named Zhelaizhai may be the ancient city of Liqian recorded in the Han Shu, or Book of Han, a classic Chinese book that records the country's history during the Western Han Dynasty from 206 BC to 25 AD.

Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 220) documents also mention that a Han army led by General Chen Tang encountered a 145-soldier detachment that marched in "fish-scale" formation as part of Zhizhi Chanyu's forces. They used round shields and fought bravely and efficiently but were eventually crushed by the Han cavalry. Dubs speculated they were the Roman soldiers captured by Parthian troops and used by Zhizhi Chanyu as mercenaries.

The Western Han Empire was impressed by the soldiers' courage and fighting abilities. It gave them land and incorporated them into its army to defend its eastern border.

Harris and many Chinese researchers, including Lanzhou University professor Chen Zhengyi, researched the history in the late 1980s. Their publications, including Harris' Black Horse Odyssey, Search for the Lost City of Rome, which stirred global interest in the tiny hamlet.

In 1999, the local government changed the village's name back from Zhelaizhai to its old name Liqian to attract investors and tourists.

Many domestic and foreign media have since visited the village to meet the "Roman descendents".

|

|

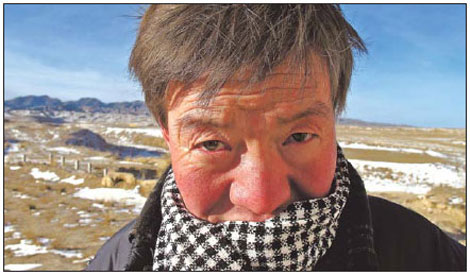

Sun Jianjun has done countless interviews about his European appearance. |

The theory also inspired ordinary villagers' imaginations.

All tombs in Liqian face West, and villagers have retained such customs as bullfighting and making a type of pie that resembles pizza. Yongchang resident Li Jinlan even claimed she was suddenly able to speak Latin after recovering from a serious illness and could tell previously unknown stories about the Roman legion.

But the myth's hold hasn't been able to compete with urbanization's magnetism, and many of the "Roman legion's descendents" have left for cities.

Even in the harvest season, Li-qian resembles a ghost town. Most residents have moved to Yongchang town, 20 km from the hamlet, or to Jinchang city, where the discovery of rich nickel deposits has led to a proliferation of energy plants.

Despite being a shy man of few words, 33-year-old Sun Jianjun has accepted countless interviews about his European appearance. But, like everyone else, the man with naturally brown hair and blue eyes has to face the reality of the bottom line - that is, feeding his family and providing them with a better life.

Sun moved his family into a rented apartment in town six years ago. He does odd jobs, usually earning about 70 yuan (8 euros) a day. "I am busy working now. I don't have time for interviews," Sun says with a thick local accent. He only accepts interviews arranged by the local government's cultural and publicity departments.

Luo Ying, another famous "Roman descendant" from Liqian, who has deep-set eyes and a hooked nose, is now working on the construction site of the new airport in Jinchang city.

Luo went to Beijing in 2006 for a DNA test arranged by the Institute of Archeology under the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. It was discovered he is genetically 46 percent Caucasian. Luo politely refused an interview with China Daily. He isn't allowed to leave the construction site during work hours and doesn't want to lose his job, he says.

But not everyone agrees with the legion theory, and so the academic debate rages on.

Retiree Chen Zhengyi is one of China's most zealous advocates of Dubs' theory.

"How did a village suddenly appear on Han Dynasty territory that was recorded as a war prisoner settlement? Why was the village named 'Liqian', which sounds like 'legion'?" he says. "It can't be simply explained as a coincidence."

Chen has published academic papers and books to support his theory.

But Beijing Normal University professor Yang Gongle points out interracial marriages were common on the ancient Silk Road. "The villagers' European traits aren't enough to prove they are the Roman legion's descendants."

Lanzhou University scholar Liu Guanghua points out the "fish-scale" formation was used earlier in China.

Liu is also skeptical, because the region has long been inhabited by various ethnic groups and is connected to Central Asia.

A 2007 DNA test administered to 93 villagers by Lanzhou University's School of Life Science found 77 percent of villagers were closely related to Chinese ethnicities, mostly Han.

But folk researcher Song Guorong, who has long collected portraits of Liqian villagers, believes the DNA test results don't disprove the theory.

"The Roman empire covered vast territories, and many soldiers in the legion were mercenaries," he says.

But Song also admitted the theory lacks archeological evidence, such as Roman coins or weapons. The only physical artifact discovered in the area is a human skeleton believed to belong to a Roman soldier because it is 1.8 meters tall.

E-paper

Ear We Go

China and the world set to embrace the merciful, peaceful year of rabbit

Carrefour finds the going tough in China

Maid to Order

Striking the right balance

Specials

Spring Festival

The Spring Festival is the most important traditional festival for family reunions.

Top 10

A summary of the major events both inside and outside China.

China Daily in Europe

China Daily launched its European weekly on December 3, 2010.