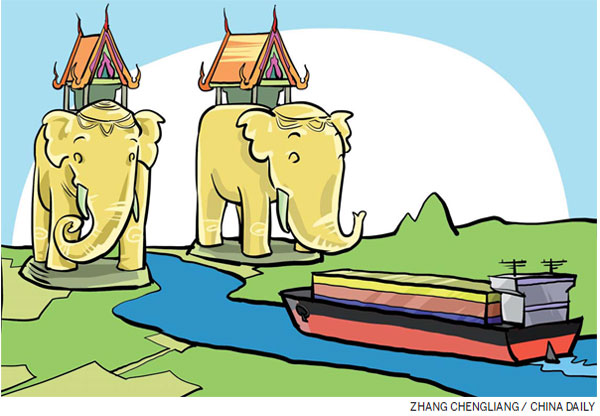

New grand canal promises trade boon

Updated: 2015-08-14 08:55

By David Gosset(China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||||

Some people and governments still need to be convinced of Thai channel's benefits

China's Belt and Road Initiative will gradually reshape Eurasia, but within this grand vision of a new Silk Road, it is the construction of the Kra Canal in southern Thailand that could have the greatest impact.

No official announcement has been made on the realization of this gigantic infrastructure project, but some analysts and business insiders are expressing support for a waterway that would connect the Andaman Sea and the Gulf of Thailand at the latitude of the Kra Isthmus, the narrowest part of the Malay Peninsula in southern Thailand.

The canal, which would cost at least $30 billion (27 billion euros), about 8 percent of Thailand's GDP, and take 10 years to build, would obviously create jobs in the country and beyond, but it would also facilitate global trade and stand as a symbol of international collaboration.

An artificial channel connecting the Indian Ocean and the Far East would affect the geopolitical dynamics of Southeast Asia but would not have to be detrimental to the core interests of Singapore, whose proximity to the Strait of Malacca has been an element of its success.

In the context of rapidly growing economic exchanges between Asia, western Eurasia and Africa, the Kra Canal would not be a substitute for the Strait of Malacca but a necessary complement. A quarter of internationally traded goods crossing the Strait of Malacca have congested the stretch of water between the Malay peninsula and Sumatra. As China heads toward becoming the world's largest economy, the opening of another trading conduit closer to continental Southeast Asia is the answer to an objective need.

In the long term, the flourishing economy of Thailand would not hurt any member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, but the prosperity of 67 million Thai people would enrich an increasingly important grouping.

By shortening the distance between the Indian Ocean and the Far East by more than 1,000 kilometers, the Kra Canal would benefit international business. It would also create new opportunities for the countries located close to the new route. In shaping a general diplomatic environment favorable to the realization of the artificial waterway, the options offered to Myanmar and Vietnam should be studied and emphasized.

It is little surprise that in Thailand there are some who are not swayed by the idea of the canal. You cannot expect a complex project to generate unanimity in a society known for frequent internal squabbles, but a properly thought-out and explained plan would win the support of the great majority who care about their country's future.

If Thais want to better understand how the canal could benefit their country they could do no better than studying the benefits that the Suez Canal delivered to Egypt. With special economic zones integrated south and north of the canal, Thailand could enter one of the most prosperous periods of its long history. Far from exacerbating existing tensions in southern Thailand, the Kra Canal would have the opposite effect, rebalancing the distribution of Thailand's economy. The capital, Bangkok, accounts for 30 percent of the country's economic output.

Rather than dividing Egypt, the Suez Canal plays a unifying role, the Al Salam Peace Bridge that crosses it at El Quantara linking Africa and Eurasia. Similarly, a bridge over the Kra Canal would ensure the continuity of transport on the north-south axis of the Malay Peninsula.

Even if incidents caused by the ethnic and religious insurgency in the Patani region in the three southernmost provinces of Thailand do not prevent 3 million tourists every year from enjoying Phuket, which is also located in the south of the country, some observers still argue that it would be too risky to invest in a massive project in a zone where tensions may erupt. But was Egypt a model of stability under Ismail the Magnificent (1830-1895)? The largest public engineering work of the 19th century was realized despite the significant risks, and over the years the 193 km long Suez Canal has positively modified the map of global trade and largely benefited Egypt. It now generates about $5 billion a year in revenue for the country.

When opponents of the Kra Canal say that if it is such a good idea it would already have been built, they seem to be unaware that new factors have created an entirely new situation: the 21st century Chinese return to centrality accompanied by the great leap outward of global China provides the means and the need to realize the Kra dream now.

Working with Thailand, China, which built the 1,776 km Grand Canal 1,300 years ago, obviously has a key role to play in the realization of a new trade nexus but it would be in the interests of both countries to remain open to other sources of investment and expertise.

When in the 17th century, during the reign of Louis XIV (1638-1715), Pierre-Paul Riquet began building the Canal du Midi, King Narai (1633-1688) asked the French engineer De Lamar to look for the first time into the feasibility of the Kra Canal. Two centuries later, the father of the Suez Canal himself, French diplomat and entrepreneur Ferdinand de Lesseps, visited the Rattanakos in Kingdom and expressed his support for the project.

Preoccupied by the problems he encountered with the Suez Canal, Ferdinand de Lesseps was never able to really focus on a new Asian enterprise. More importantly, Chulalongkorn, Rama V (1853-1910), who had to neutralize French ambitions in Indochina by using the British Empire in order to maintain the independence of his country, could not antagonize the British by challenging their interests in Singapore, the outpost that Thomas Stamford Raffles had created seven decades earlier.

An inclusive enterprise, the long-term success of the Kra Canal will also be largely determined by the governance of its operations, and in that matter Bangkok can find inspiration from the Suez Canal Authority or the Panama Canal Authority. It should also be ready to create a governing structure that takes account of contemporary local, regional and international dynamics.

Misconceptions about the nature of China's re-emergence have produced the "China threat" discourse, and those who cultivate this narrative or those who simply believe it will misinterpret Beijing's involvement in the Kra Canal as a threatening projection of Chinese power. One can expect that the United States will first use its diplomatic influence and its soft power to oppose the canal as much as, at some point, the United Kingdom of Queen Victoria tried to oppose the French initiative in Suez. However, we must not forget that in a spirit of openness and inclusiveness Ferdinand de Lesseps was finally able to gain London's support.

Following open debate and convincing explanations on the collective benefits of the Kra Canal, the US will have to recognize that in an evolving world new initiatives that do not come from the West are not necessarily anti-Western; they are simply the mark of a multipolar world.

The author is director of the Academia Sinica Europaea at CEIBS and founder of the Euro-China Forum. He has established the New Silk Road Initiative. The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

(China Daily European Weekly 08/14/2015 page10)

Today's Top News

Turkey's early elections 'decidedly possible': PM

Death toll rises to 50, military sends chemical specialists to blast site

12 firefighters among 44 killed in explosions

Chinese yuan extends fall Thursday

China rattles a few cages in the world's financial markets

Tibetan drivers to finally see the end of 'death road'

China becomes world's largest robots market for second consecutive year

Yuan may stumble, but will not fall

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|