The right to rule

Updated: 2014-12-05 08:47

By Huang Weijia(China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||||

Holding power a weight matter 权力是一种游戏

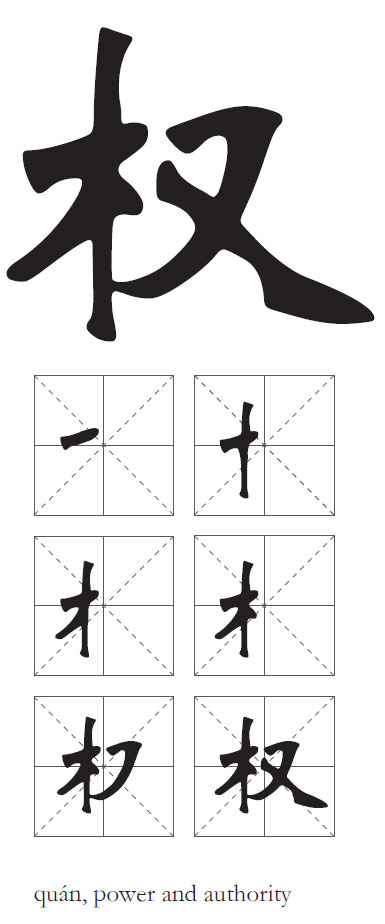

The character 权 (quán) is the ultimate symbol for power and authority in Chinese. Such power, or 权力 (quánlì), may stem from an incredible amount of wealth or prestige and reputation. But 权 is not just reserved for the rich and famous. 权利 (quánlì), though pronounced the same, means rights, something everyone can understand.

As to the origin of 权, some say its earliest form referred to a particular kind of plant, which was exemplified by the 木 (mù, wood, plant) radical on the left. The right radical used to be 雚 instead of 又, which was simplified in modern times, cutting all 17 strokes to merely two for easier use.

|

The bronze statue of Qin Shi Huang (260-210 BC), the first Chinese emperor who was the most powerful man in the country. Photos provided to China Daily |

For a more plausible explanation for the evolution of the character, we need to look at its other early meaning, which is as an instrument for measuring weight, or what would have been the sliding scale of a steelyard. It was also used as a verb, meaning to weigh. For instance, when philosopher Mencius was warning King Xuan of Qi in the Warring States Period (475-221 BC) to be cautious of his decisions and rule with benevolence, he said: "By weighing, we know the weight; by measuring, we know the size. All things require study and reflection to learn, and motions of the mind are especially so." He went on to beg the king to reconsider his decision of war and instead implement a benevolent policy to better his rule.

With the same root, the word 权衡 (quánhéng) originally referred to the sliding weight of the steelyard and its arm and now means to weigh and assess. 权衡利弊 (quánhéng lìbì) means to weigh the pros and cons.

Because the scale, as an instrument that can measure definite weight, was considered authoritative, ancient Chinese began to use the steelyard as a metaphor for 权力, or power of authority, and 权势 (quánshì), meaning power of influence. Officials with influence became known as 权臣 (quánchén), literarily powerful officials. Those in positions of great authority were given the name 权贵 (quánguì), or bigwigs.

The two concepts of authority and influence in power have continued into today. For example, 大权在握 (dàquán zàiwò), literally to have great power in one's palm, which means to have total control over something, is a fitting word to describe dictators. Where there is power, there is struggle, hence 权力斗争 (quánlì dòuzhēng, power struggle). The sensational HBO TV drama Game of Thrones is translated to Game of Power (《权力的游戏》 quánlì de yóuxì) in Chinese.

In reality, there is no lack of such games. To usurp the position and seize power, or 篡位夺权 (cuànwèi duóquán), originally meant to wrest power and status from a monarch, now adapted to 篡党夺权 (cuàndǎng duóquán), literally meaning to usurp the Party and seize power, a phrase used to condemn the notorious "Gang of Four" for their doings during the cultural revolution (1966-76).

People with influence naturally dominate and have superiority over others, producing military terms like 制空权 (zhìkōng quán, air supremacy), 制海权 (zhìhǎi quán, naval supremacy) and 主动权 (zhǔdòng quán, initiative).

The word 权利 is pronounced just like 权力, but has a different meaning. It is a combination of 权, power and 利, benefits and traditionally represents influence and wealth. However, in modern usage, 权利 indicates citizens' rights, privileges and authority under the law, such as 生存权 (shēngcún quán, right to live), 生育权 (shēngyù quán, right to bear children), 宗教信仰自由权 (zōngjiào xìnyǎng zìyóuquán, right to hold religious beliefs freely), 隐私权 (yǐnsī quán, right to privacy), and ultimately, 人权 (rénquán, human rights).

Courtesy of The World of Chinese, www.theworldofchinese.com

The World of Chinese

(China Daily European Weekly 12/05/2014 page27)

Today's Top News

US, Britain pledge to support Afghanistan

HK visit: A political kabuki

Ukraine unlikely to join NATO in near future

Hotpot chain to raise $129m

2014 likely to be record warmest year

Ukraine's ceasefire talks continue

China marks 1st Constitution Day

Outbound tourists hit record 100m

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|