A lot more than just reaching for the sky

Updated: 2014-09-19 07:41

By Antony Wood and Daniel Safarik(China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||||

China's tall buildings represent progress for some, but aloof, energy sappers for others

China is the world's most active tall building market, by far, and by the end of next year, it is estimated that one in three buildings taller than 150 meters in the world will be in the country.

With about 250 million people set to move into Chinese cities in the next decade or so, the pace of urban construction, including road, rail and water infrastructure and cultural institutions, in addition to tall buildings, has outstripped any previous period in human history.

Many of the iconic towers now rising in China have lent world recognition to cities that relatively few Chinese, let alone Westerners, were previously aware of.

These mega-projects have provided a global stage for once-obscure Chinese cities and companies, and a veritable creative playground for Western architects faced with a much more conservative building climate at home.

This has gone hand-in-hand with the rise of a middle class that never before had the kind of purchasing power it does.

This mega-trend raises important questions that need to be answered urgently.

Despite the booming construction trend, it needs to be acknowledged that tall buildings are by no means accepted by all as a truly sustainable building type, and the reasons for this bear investigation.

In China, certain issues are particularly acute:

First, it has been said that "skyscrapers are built equations". Left purely to economic forces, tall buildings can have a homogenizing effect on cities.

In China this has been particularly true, as a function of the number of, and speed with which, tall buildings are being designed and built.

Even when designed by Chinese architects, many recent tall buildings have no relationship to the cities in which they are built, and seem aloof and apart from their communities.

The lack of reference to, or integration with, local culture and history can make these buildings seem alien and imposing, and eliminates the individual sense of identity these cities once had.

The sweeping scale of tall buildings is impressive on the skyline, but they become oppressive at ground level, especially when little thought is given to the pedestrian realm.

This is compounded in countries like China, where not just new tall buildings, but entire new cities are being created.

Too often, the human scale is not a priority, and tall buildings have contributed to the dwarfing sense of scale and agoraphobic effects already wrought by multi-lane highways, superblocks and massive civic buildings set on platforms.

We must ask: Are cities for people, or for the display of buildings?

Second, in China there is a particular struggle between the desire to breathe cleaner air and the need for buildings to foster engagement with their environments.

In some cases, the solution has been to hermetically seal buildings and filter out the particulates in the smoggy urban atmosphere.

This can improve physical health but increase psychological isolation.

Some, though fewer, buildings have substituted sky gardens or incorporated methods for drawing cooler, cleaner air down from their peaks into the main body of the building. This can also be problematic as it creates an unfair advantage for occupants of those buildings, which may not be public.

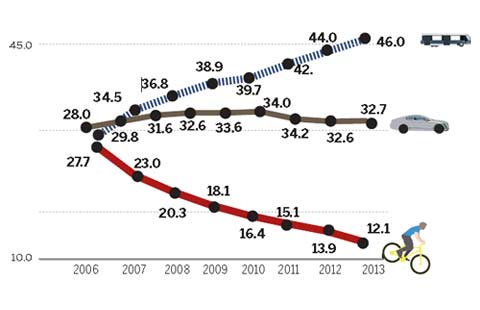

Third, tall buildings use a great deal of energy, and special design considerations must be undertaken to make them more sustainable.

Rapidly developed skyscrapers in China and elsewhere often neglect this, and their isolation as islands reachable only by car worsens their environmental profile. Strategic thinking must be deployed to offer tall buildings that positively contribute to urban sustainability.

Some tall buildings have been built speculatively without a realistic assessment of whether there will be enough occupiers when they are completed. The result has been cities with mostly-empty ghost towers that hulk dimly on the skyline, attract vagrants, vandals and unsafe storage practices, and tend to scatter, rather than attract, urban life.

Tall building development in some cities has become synonymous with site clearances and the elimination of historic buildings and urban grain - the study of the form of human settlements and the process of building pattern - with the resulting buildings realized as gratuitous sculptural forms that have no relation to Chinese culture or environment.

Fourth, tall buildings would also be potentially associated with other serious issues, such as corruption.

In China, the government owns the land and sells it to developers, increasing the potential of decision makers approving major projects to which they have financial ties.

The national government of late has cracked down on city officials accepting any monetary contributions or lavish gifts, and as one of the most important building types in China, tall buildings seem to have become a part of the scrutiny in some cases.

The danger is that tall buildings become associated with corruption, that the nation sours on tall buildings entirely, and China's urbanization begins to take other, less sustainable forms (such as replicating the post-World-War-II North American suburbanization model). The objections to tall buildings on cultural and environmental grounds are certainly legitimate.

The solution to problems of urbanization must necessarily draw from much more than a prescription for more tall buildings, regardless of their scale or location.

But there is clearly great potential for tall buildings to become an integrated part of the solution. This is not a question that deserves a simplistic answer, as our increasingly urban population's survival really does depend on it.

The reality is that we might never achieve "net-zero" or other absolute thresholds of sustainability in tall buildings, and we are highly unlikely to achieve it if the embodied energy of the materials to construct the building - and other aspects of the whole building life cycle - are factored into the equation.

The best we can perhaps do is strive to reduce both embodied and operating energy to the absolute minimums required, and then take solace in the fact that it is the bigger urban-scale contributors outside the building - the benefits of increased urban density, reduced infrastructure, shared facilities, better land use - that is tipping the scales in favor of the tall building, rather than the building acting alone.

It is certainly in this area, the building's full integration into the infrastructure of the city, that we need to increase our efforts.

Tall buildings are becoming more prevalent in more corners of the world. However, the fact remains that many tall buildings are not brilliant pieces of architecture, and are generally homogenizing the urban centers they populate.

We now have the ability to go much higher, with much greater speed than ever before, but we must also build better by directly relating every building to its physical, cultural and environmental context.

In the face of unprecedented global population growth, urbanization, pollution increase and climate change, it is no longer enough to simply create buildings that minimize their environmental footprint.

Reducing of operating and embodied energy consumption in every building is, of course, vitally important, but even this is probably not enough to mitigate the huge issues at stake.

We need to start considering how every building can start working with others in a harmonious urban whole, by maximizing urban/building infrastructure, sharing resources, generating and storing energy, and looking for completely new ways to improve the building's contribution to the city; physically, environmentally, culturally, and socially.

Cities thus need to be thought of, and buildings planned for, in all three dimensions:

They cannot just be vehicles for isolated programs and expressed as products of two-dimensional zoning plans and height limits.

Each stratified horizon of a tower has an opportunity to draw from the characteristics of the city and external environment, both of which vary widely with height.

Wind, sun, rain, temperature and urban grain are not the same through 360 degrees of plan or 360 meters of height, and our buildings need to both recognize, and draw opportunity from that.

Antony Wood is executive director of the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat; and Daniel Safarik is an editor with the organization.

(China Daily European Weekly 09/19/2014 page7)

Today's Top News

'Yes' in Scotland could be 'maybe' for Chinese firms

Cooperation helps extradite fugitives

Xi, Modi set friendly tone for visit

Collector has 'proof' of atrocities

Naked newborn survives typhoon

How Alibaba IPO learnt from Facebook's mistake

Russia to beef up troops in Crimea

10 problems of Chinese society

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|