Race to the top

Updated: 2014-09-19 07:41

By Joseph Catanzaro, Chen Yingqun and Zhang Min(China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||||

Towering ambitions have made China world's tallest country

On a construction site in Tianjin, where an army of 2,800 workers haul and hammer and weld night and day, the highest man-made point in northern China is rising daily.

The partially completed skyscraper is called 117, and it is growing taller at a blistering rate one floor every four days.

But that is not fast enough for Zhang Songkun, chief engineer for GoldIn Properties, the investment company behind the 16 billion yuan ($2.6 billion; 2 billion euros) project.

"In Shenzhen, we complete a floor every three days," he says.

The 117 building is already taller than the Shard in London, Mercury City Tower in Moscow and the Empire State Building in New York City. When it is finished at 597 m, it will be the second-tallest building in China, but that ranking will be short lived.

Not long after tools are downed on what will soon be China's tallest building, the 632 m Shanghai Tower, it too will lose its crown.

Usurpers with lofty ambitions, mega-towers destined to reach heights of 636 m, 660 m and 700 m, are already rising in Wuhan, Shenzhen and Suzhou.

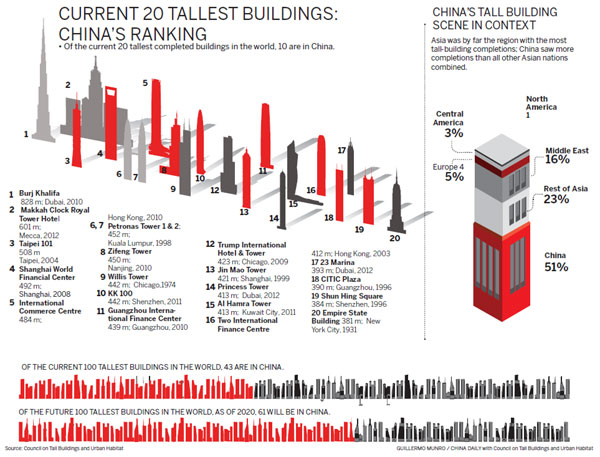

With more buildings over 150 m than any other nation, China is now the tallest country in the world, and it is reaching for the sky at a phenomenal rate.

By 2020, 13 of the top 20 tallest buildings in the world will be in China, which until 1995 had only 10 buildings that were 200 m or taller, and before 1980 had none at all.

It is a vertical building boom the likes of which the world has never seen.

But the drivers and implications of this great leap upward, in which more than half the world's 200-m-plus skyscrapers finished last year were in China, are now starting to be questioned.

While some warn that all this will come crashing down, others are adamant that in China the future is in looking up.

Antony Wood, executive director for the peak global representative body, the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat, says China's building boom turned all predictions on their head.

"The reality is, 20 years ago China had no tall buildings," he says.

"If you predicted the tallest buildings in the world 30 years ago, you would have said three things with certainty: they will be in North America; they will be office buildings; and they will be built out of steel. The exact opposite is true. The tallest buildings in the world will be in Asia, they will be residential or mixed-use function, and they will be concrete or composite construction."

Wood says the most obvious driver for China's density rush is the rapid urbanization of the country's 1.3 billion people, which has now passed the 50 percent mark and is expected to reach 60 percent by 2020.

And compared with other high-rise-heavy countries like Saudi Arabia, where the 1,000 m Kingdom Tower will soon supplant the 828 m Burj Kalifa in Dubai as the world's tallest building, Wood says China's move upward is predominately being driven by real market demand and paid for by a mixture of private and government-backed developers.

"China has the fundamentals that, I think, make sense as to why it is creating densification in its cities," Wood says.

But in a country as vast and varied as China, Wood concedes not all of the motivators for the vertical explosion appear entirely "healthy".

What he calls "city branding" could herald some problems and create an oversupply in the short term, he says.

"Using a tall building to brand something has always been a driver. But 60 to 80 years ago, this branding was about a commercial cooperation: The name of the tower was the name of a company. Now they are more likely to be Shanghai Tower, Russia Tower, Chicago Spire. Tall buildings are now being used to brand cities in a competitive world market, the same way as car companies used tall buildings to brand themselves in the 1930s in New York. It's the same phenomenon but the scale has shifted."

Professor Wang Weiqiang of the college of Architecture and Urban Planning at Tongji University in Shanghai believes rivalry for status and prestige, rather than genuine market drivers, is behind the upward building boom in some Chinese cities.

"There's a risk that the frenzied building of skyscrapers will leave some buildings empty in the end," he says. "Urbanization is not about developing all land at the same time."

In the shadow of the towering hive of activity that is 117, Zhang keeps a small office where blueprints line the walls, and a chrome-plated hard hat gleams in one corner.

"Of course there is competition (between cities and developers)," he says. "We wanted 117 to be unique and the best. But unexpectedly some cities are building even higher."

Over the course of his career in China, the 65-year-old has erected 24 buildings that are more than 100 m tall. That is roughly the equivalent of a quarter of all the tall buildings in Paris.

Zhang says 117, named after the number of floors, will be a city branding icon for Tianjin.

"Every city needs an iconic building. If it doesn't have one, it will be less attractive to business."

Six years ago, when developers Financial Street Holdings put down 3 billion yuan to build the Tianjin Jinta tower, they felt the same.

Besieged by a forest of construction cranes and sprouting structures, the 336.9 m Tianjin Jinta retains its "iconic building" status, but only on a technicality. A mere three years into its tenure as Tianjin's tallest it has lost its crown to the only partially completed 117.

"Tianjin Jinta is by far the tallest completed building in the city that is currently in use," project director Li Yifan says.

The building, in the heart of the city's financial district, with 193 companies and 9,000 workers occupying most of its floor space, was the answer to urban sprawl and high land prices frustrating a demand for more real estate, Li says.

The numbers prove it was a solid, market-driven investment, he says, even while conceding the tall tag has been a big draw card.

"Seventy-five percent of this building is rented out at about 180 yuan a square meter a month," he says. "Yes, there are many tall buildings in Tianjin, but the market has also been growing. Our rents in the first half of this year made us more than the entire previous year.

"Compared with other buildings, skyscrapers are iconic. Companies that take up space in these buildings are after a positive image."

Shu Wenbin, vice-general manager of Continental Interior Design and Construction, is a working example of a Chinese business owner who believes fortunes can rise in line with floor numbers.

He acknowledges that projecting a "better image of credibility to clients" was a major reason why he decided to locate his company in a high-rent, high-rise building in Beijing.

But Wood and Zhang see greater significance in the fact that new white-collar businesses such as Shu's are chasing space in tall buildings. They believe the rise of China's service sector is happening in tandem with the rise of skyscrapers, and that the two occurrences are partially interlinked.

Wang Yunqi, vice-chairman of the Tianjin Bureau for Promotion of Small and Medium Sized Enterprise, says the numbers show this is the case in his city.

In the past three years, 107 new buildings have gone up in Tianjin. Service-sector growth has kept pace, and now accounts for 48.1 percent of the city's economy, he says. The tax generated from businesses in tall buildings has also shot up to account for 60 percent of the local government's total revenue.

"Urbanization helps transfer the labor force to the modern service sector and provides a new platform and opportunities for employment," he says.

But Wang concedes that there are "some problems" with Tianjin's push upward.

"The vacancy rate is a little bit high," he says. "At present, the whole city's (vacancy) rate is about 25 percent, while in the central areas it is about 10 percent. But in some counties and districts (in Tianjin) the rate is as high as 40 percent."

Professor Wang says that in many big cities like Shanghai, the approvals process for tall buildings is now much more stringent and takes longer.

Wood says he believes first-tier cities have intentionally cooled down the number of skyscrapers going up, and are getting the ratio right. But he says some second- and third-tier cities could be building too many, too fast, in the short term.

"I think there is most definitely an oversupply (of tall buildings) in some (Chinese) cities."

But it may be too early to tell definitively whether or not some areas in China will experience a tall building oversupply problem, he says.

"We need to remind ourselves the Empire State Building, for the first 10 years of its existence, was called the 'empty state building' because no one had the money to rent space in there and it took 10 years to fill up. Do we remember that? No, it's an icon in New York and it's only ever discussed in positive terms, but I bet if you'd discussed it five years into its existence people would have said, 'What a white elephant.'

"They are now going on site in Suzhou with what will be China's tallest building, (the Suzhou Zhongnan Center). You think to yourself, 'Suzhou, it's a tiny sleepy town on the edge of Shanghai. Can it really sustain that?' Suzhou has a population of 10 million. There are only four or five cities in the whole of the US that have a population of more than four or five million. So on the one hand it is sleepy Suzhou, but on the other, with 10 million people it has got a dynamic all of its own."

Russell Gilchrist is the Shanghai based design director and leader of the tall building practice niche for Gensler, the global architectural firm that designed Shanghai Tower and what will eventually be China's new tallest building, the 700 m Suzhou Zhongnan Center.

He is concerned about both the quantity and the quality of buildings appearing in some areas of China.

"The stories of ghost towns and cities in China does apply to some of the tall buildings going up at the moment," he says. "I know there are a lot of buildings going up, but I'm not quite sure the occupancy of these buildings is matching the speed at which they are going up.

"A lot of the buildings are going up fast. You see it every day. But the quality is not always what we would expect in other parts of the world. With the (Chinese) economy slowing up a little bit, we've noticed a slight tail-off already in most market areas. I just wonder if the lesser-quality buildings will just stand there redundant, or even worse, in three or 10 years time be pulled down and redeveloped."

Gilchrist believes that the next building trend in China will be a market-driven focus on producing extremely high-quality tall buildings, in the vein of Shanghai Tower.

"There will be more emphasis on higher-quality buildings," he says. "There are projected to be 500 new multinationals coming to Shanghai in the next 10 years. Their expectations and aspirations are not going to be based on the current China market. They are going to be based on what they know and love in Europe and elsewhere."

One point on which Wood and Gilchrist strongly agree is that more tall buildings and greater urban density can potentially help China tackle some of its current environmental woes.

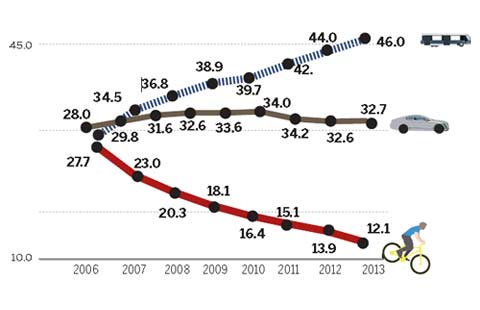

Reducing urban sprawl can pull air-pollution levels down by taking cars off roads. The energy efficiency achieved through mixed-use skyscrapers, where office, residential and hotel space naturally staggers peak period demands on resources like electricity, is similarly beneficial.

This concept of "sustainable vertical urbanism" was the primary focus of global experts and industry stakeholders who gathered in Shanghai in mid-September for a Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat conference.

But while the potential is there for tall buildings to be a force for good, both Wood and Gilchrist say planning and foresight are crucial for achieving a positive impact, and this is something they say is not always happening in China right now.

"You have to be careful where you put them," Gilchrist says. "The last thing you want to do is put a high-rise building that houses 10,000 people somewhere that means all of them have to drive to get to work. The justification for building tall is often being located next door to a subway station. That's when it starts to make sense."

Out on the edge of Tianjin, where 117 is expected to reach 500 m by the end of this year, Zhang says the fact that the building is about 16 km from the financial district will not prevent it from becoming an icon that defines the city: Perhaps, he suggests, in a very tangible way.

"I would suggest the government make 117 the new center of Tianjin," he says. "Plan the rest of the city around it."

Wood says that overall he believes China is getting it right with its push for urban density.

"I think China is in a fantastic situation. You only really get one opportunity to develop a country. Every country has its heyday, and this is China's turn. It's got a great opportunity to try to do things better than other countries have done, and I think it has. Nothing was built in a day, and it takes time. I think China has every reason to be optimistic."

Contact the writers at josephcatanzaro@chinadaily.com.cn and chenyingqun@chinadaily.com.cn

Liu Kun contributed to this story.

|

From left: Antony Wood, executive director for the peak global representative body, the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat; Russell Gilchrist, the Shanghai-based design director and leader of Gensler; and Zhang Songkun, chief engineer for GoldIn Properties, the investment company for 117. Photos Provided to China Daily |

|

Skyscraper 117 will become the tallest building in Tianjin. Su Hang / China Daily |

(China Daily European Weekly 09/19/2014 page1)

Today's Top News

'Yes' in Scotland could be 'maybe' for Chinese firms

Cooperation helps extradite fugitives

Xi, Modi set friendly tone for visit

Collector has 'proof' of atrocities

Naked newborn survives typhoon

How Alibaba IPO learnt from Facebook's mistake

Russia to beef up troops in Crimea

10 problems of Chinese society

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|