Family planning fine-tuning not enough

Updated: 2014-02-14 08:47

By Yang Ge (China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||||

Social security and old-age pensions must be overhauled as demographic shift begins to bite

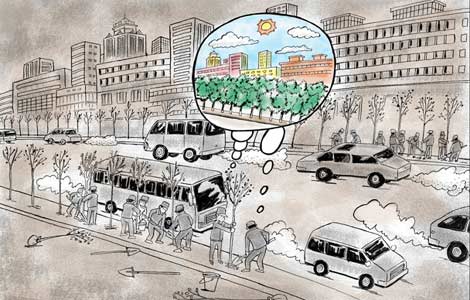

Visualize young people toiling all day just to support the increasing number of senior citizens. Does that sound troubling? Well, that could become reality if the current trend of population growth continues.

Statistics show that China's working-age population, those between 15 and 59 years of age, will soon reach its peak and then start declining. As a result, the shortage of high- and middle-end workers will continue and the supply of low-end labor force will drop. This, in turn, may raise labor costs and pose a grave problem for the country's labor-intensive industries.

In addition, the aging population poses a challenge to the social security system as more senior citizens need medical care and pensions.

China's decision-makers have realized the problems. On Nov 15, the Third Plenary Session of the 18th Communist Party of China Central Committee issued the Decision on Major Issues Concerning Comprehensively Deepening Reforms, which, among other things, has adjusted the family planning policy.

During its initial years, the family planning policy, which allows most couples (especially in urban areas) to have only one child, helped optimize the country's demographic makeup. Owing to the generally low fertility rate, the percentage of children in the 0-to-14-year age group fell from 27.7 in 1990 to 16.6 in 2010, and the percentage of senior citizens aged 65 and above rose from 5.6 to 11.9. With the population dependency ratio dropping from 49.8 to 34.2 in those 20 years, the population offered sufficient labor force to propel China's economic rise.

But a low fertility rate cannot keep the population structure at the optimum level forever. The change came in 2010, when the percentage of working-age population started dropping by 0.3 a year and there was a corresponding fall in the fresh supply of labor. If China's low birth rate continues, the working-age population will be less than 60 percent in 2040, while the population dependency ratio will rise to 62.4 in 2050.

Thus the adjustment in the family planning policy was necessary. For one thing, it can raise the general fertility rate, which lingers between 1.4 and 1.5, by 0.3. That would lead to 1-2 million more births every year and a larger workforce 20 years later. Relatively, the percentage of senior citizens would drop too.

But it would be naive to believe that the adjustment in the family planning policy will reverse the general trend of China's demographic change in the near future. Changes in demographic structures usually happen very slowly, and the effects of a policy could take decades to become evident. According to United Nations Population Fund estimates, even if the total fertility rate of Chinese women of childbearing age reaches 2 by 2020, the percentage of senior citizens above 65 years would still increase from 9.4 in 2010 to 27.2 in 2050, raising the population dependency ratio to 78.2.

With more children being born, the population dependency ratio may even rise in the short term, because the aging process of the population is not likely to be effectively curbed until 50 years after the policy is introduced.

What has happened in other countries shows how long it takes for policies encouraging births to bear fruit, although reverse policies like family planning can curb population growth more efficiently in a shorter time. The seeming dilemma has its own logic in social development. As we transform from an agricultural society to an industrial one, family-based production yields place to person-based production. As a result, the responsibility of caring for the elderly passes on, though gradually, from families to society, making more couples reluctant to have children. For example, Japan and some Western European countries have for some time been encouraging their citizens to have more children with little success.

Adjusting the family planning policy alone cannot solve the problems created by an aging society, which poses the biggest challenge to China's economic growth. To tackle the problem, the government has to spend more resources on social security, old-age pensions and medical care. Apart from supporting its aging population, China also faces the tough challenge of rising labor costs. This is a serious problem given the abundance of labor-intensive industries in the country. Therefore, China must, sooner rather than later, speed up its industrial upgrade to attain a better position in the global industrial chain.

The author is an assistant professor at the Institute of Population and Labor Economics, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

(China Daily European Weekly 02/14/2014 page9)

Today's Top News

Germany, France eye new data network

No much progress in Syria peace talks

Lantern Festival fires kill 6 in China

China urges US to respect history

KMT leader to visit mainland

11 terrorists dead in Xinjiang

Illegal detention reports probed

4 die in Austrian train-car crash

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|