Easing money policy would harm rather than help

Updated: 2011-12-02 15:46

(China Daily European Weekly)

|

|||||||||

With the economic slowdown and monetary easing in the US and Europe, China can expect a surge of liquidity

|

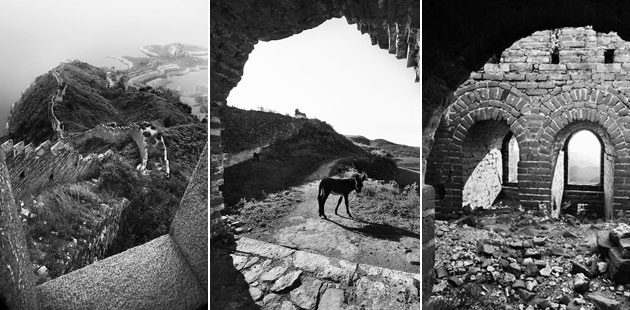

Zhang Chengliang / China Daily |

The recent worsening of the European sovereign debt crisis and alarming deterioration of the economic recovery in many developed countries have put many central bankers to a new round of tests. Faced with increasing risk of recession, the European Central Bank decided to cut its benchmark interest rate and start another round of monetary easing. Many investors and observers feel China will probably repeat what it did when it faced the 2008-2009 global financial crisis: to follow the West and reverse its relatively tight monetary policy soon.

The Chinese government should not relax its curbs on the real estate market and monetary policy now, and I do not expect it to start a new round of credit easing in the near future.

To better understand the policy motives, it helps to understand the background in which developed countries are going for a new round of monetary easing.

First, the US has been contemplating a new round of asset purchases, also known as quantitative easing 3, and the European Central Bank surprised the market by cutting its benchmark interest rate by 25 basis points. The main motive spurring monetary easing is an economic recovery that for developed countries is so feeble that it is unacceptable. After achieving a short-term success of boosting the economy and market sentiment, the US Federal Reserve's two previous rounds of asset purchases were judged to have come up short.

In particular, US GDP growth slowed much more quickly after the second round of asset purchases than after the first round, indicating the waning impact of quantitative easing. Nevertheless, facing the mounting problem of the sovereign debt crisis and the possible forced exit of Greece from the EU, central bankers in developed countries have few alternatives left in their arsenal. The president of the European Central Bank, Mario Draghi, has suggested that while one aim of monetary easing is to help defuse Greece's and Italy's solvency problems, the longer-term aim is to prevent the European economy from sliding into recession again.

Secondly, it is worth noting that both the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank (and in a way the Bank of Japan) have at least one worry fewer: soft prices. Indeed, one rationale for the Fed's second wave of quantitative easing has been to reduce the risk of deflation. Consequently, the central banks in the West can afford to unleash more liquidity or at least keep an unprecedented amount of liquidity in the global financial system longer, as long as growth is not returning and prices are still in check.

Finally, most developed countries enjoy free capital flow, in both directions. As a result, policy easing by the US and European central banks do not have one hundred percent of impact on their domestic economy. Instead, much of the liquidity created in the past two rounds of monetary easing was channeled into emerging markets through carry trades and eventually found a home outside the developed countries.

Investors expect higher rates of returns from emerging markets, so they vote with their feet and move the capital into other parts of the country accordingly.

Unfortunately, none of the three above arguments applies in the context of emerging markets in general and China in particular.

First, economic recovery and growth in emerging markets is bound to suffer from the slowdown in the world economy. Still, economic growth in the emerging markets is far from disappointing. In fact, following the impressive economic recovery since the G20 countries pledged to stimulate the global economy in March 2009, many emerging countries could even do with a breather to recalibrate their economic compasses and speedometers.

Like China, many emerging countries rely heavily on exports for economic growth. As wages increase in such countries in line with economic success, many realize that building such success relying on exports cannot be sustained. Hence, a slowdown in developed countries and a slowing of exports may force emerging countries to seriously re-evaluate their economic thinking and insulate themselves from the effects of economic slowdowns in developed countries in the future.

Second, unlike in the US and in most of Europe, emerging markets have faced alarming rates of inflation, as a result of the previous rounds of monetary easing in the developed countries. In certain countries such as India and Brazil, inflation even inched to about 10 percent, widely perceived as a benchmark for vicious inflation. Even before this round of easing from Europe, many emerging countries had started their campaign against inflation by raising domestic interest rates and putting curbs on money supply. Given that the economic recovery remains largely uncompromised in many countries, policymakers in some countries have indicated that controlling prices will stay at the top of their agenda for the foreseeable future.

Developed and emerging markets differ in the way they look at growth and inflation, and this poses problems for policymakers in the emerging markets. Now that it has become apparent that the emerging markets will outgrow the developed markets and that the emerging markets offer far more attractive interest rates than those in the developed markets, international capital is looking for ways to sneak into the emerging markets. Capital flow barriers in many emerging markets manage to block only part of the international capital inflow. Such excess in liquidity from the previous round of stimulus and international inflow results in asset bubbles.

This is exactly what has been happening in China. China released a huge amount of credit to the economy in 2009 and 2010 to keep it growing rapidly. Given that the government has been hesitant about reining back the liquidity and that the liquidity created in the last round of stimulus cannot find its way overseas because of capital flow barriers, money chases anything that has the potential of appreciation, be it real estate, rare jade, or ancient furniture. Many assets have had returns of more than 100 percent in the past two years.

Such sharp asset appreciation will not go unnoticed by international investors. As more and more international capital tries to exploit such bubble-like appreciation, the expectation that China will keep appreciating its currency makes a strong investment case even stronger. Just as China finally gives a sigh of relief after the market gradually digests the excessive liquidity from the previous rounds of easing, renewed easing from developed countries has prompted many emerging markets, China included, to keep as a top priority controlling capital flows and keeping prices on a short leash.

To make things worse, asset bubbles and inflation aggravate disparities in the distribution of wealth. Those on higher incomes are not particularly sensitive to inflation because daily consumption accounts for but a small fraction of what they spend. At the same time, the wealthy can benefit by investing in real estate, which has doubled in price in the past couple of years, and help offset reduced purchasing power caused by inflation. In contrast, the less well off are not just excluded from investing in asset bubbles (because they have little disposable income), but are also particularly sensitive to inflation. As a result, dissatisfaction has grown in many countries, sometimes bringing protests and serious social unrest.

In sum, monetary policy has to be forward-looking. In light of the economic slowdown and new round of monetary easing in the US and Europe, China can expect another surge of liquidity resulting from capital inflow. Consequently, even if the Chinese government decides that it has to act to further stimulate the economy, it has to take gradual steps and take account of the stimulus arising from further easing in the developed countries.

The last stimulus package and ensuing monetary easing has aggravated the already serious problem of asset bubbles and income inequality and distorted economic development growth. China can ill afford to make the same the mistake.

The author is deputy director of the Shanghai Advanced Institute of Finance. The views expressed in the article do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.