China's role in reducing carbon emissions

Updated: 2011-11-11 09:05

By ZhongXiang Zhang (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

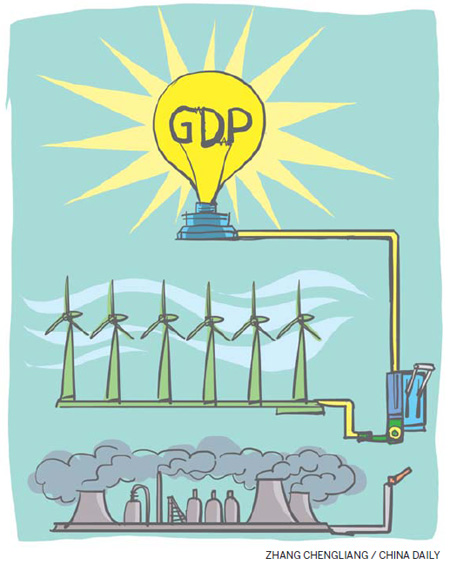

The country's proposed carbon intensity target does not just represent business as usual

Just before the Copenhagen climate change summit in 2009, China pledged to cut its carbon emissions per unit of gross domestic product, the so-called carbon intensity, by 40-45 percent by 2020 relative to its 2005 levels to help an international agreement on climate change to be reached.

While this was consistent with China's longstanding opposition to hard emission caps because such limits restrict its economic growth, it marked a point of departure from its longstanding position on its own climate actions.

While some have questioned China's willingness to act, discussion has since focused on whether such a pledge is ambitious or just represents business as usual. China considers it very ambitious, whereas some Western scholars see it as just business as usual based largely on the long-term historical trend of China's energy intensity. These issues then arise: 1) does the proposed target represent business as usual, as some Western scholars argue? 2) is the proposed target as ambitious as China argues?

Let's look at the first issue. Evaluating how challenging this proposed carbon intensity target is can be done in several ways. One is to see whether the proposed carbon intensity goal for 2020 is as challenging as the energy-saving goals set in the 11th Five-Year Plan (2006-2010). There are issues here. One is the rationale for using energy intensity reduction as a reference. Given the fixed CO2 emissions coefficients of fossil fuels, which convert consumption of fossil fuels into CO2 emissions, and given that China's energy mix is coal-dominated, cutting China's carbon intensity is in fact cutting its energy intensity. So we can use measurable and reported data on energy use in recent years to infer the stringency of China's proposed carbon intensity target for 2020.

Now to the issue of why the 20 percent energy-saving goal is considered very challenging. China has set a goal of cutting energy use per unit of GDP by 20 percent by 2010 relative to its 2005 levels. To achieve that goal, China had made significant efforts to save energy. The country closed 76.8 gigawatts of small, inefficient coal-fired power plants over the period of the 11th Five-Year Plan. This decommissioned capacity is more than the entire current power capacity of Britain.

Provinces across the country were widely reported even to have taken unprecedented measures including shutting down factories and restricting energy use in the second half of last year. Clearly, the local blackouts are not what the central government intended. However, local governments seem to have little choice but to take such irrational measures in such a very short period of time. In the end, China cut its energy intensity by 19.1 percent, falling short of the 20 percent energy-saving goal.

Moreover, the reductions in China's energy intensity have already taken into account the revisions of China's official GDP data from the second nationwide economic census issued in December 2009, part of the government's continuing efforts to improve the quality of its statistics. Such revisions show that China's economy grew faster and shifted more toward services than previously estimated, thus benefiting the energy intensity indicator.

Clearly, even having picked low-hanging fruit by closing a significant number of inefficient plants and taking advantage of the upward GDP revision helped China to get to where it now stands. China eventually failed to meet its energy-saving goal last year. However, those low-hanging fruit opportunities can only be captured once. The new carbon intensity target set for 2020 requires 20-25 percent on top of the existing target. Achieving this will clearly be even more challenging and costly for China.

Another way to evaluate whether the proposed target represents business as usual is to assess how substantially this carbon intensity target drives China's emissions below its projected baseline levels, and whether China does its part as required in order to fulfill a coordinated global commitment to stabilize the concentration of greenhouse gas emissions in the atmosphere at the desirable level.

Cutting the carbon intensity by 40-45 percent over the period 2006-2020 would bring China's carbon emission reductions of 4.8-12.7 percent below the World Energy Outlook 2009 (a flagship publication by Paris-based International Energy Agency) baseline levels for China in 2020.

So even the lower end of that range does not represent business as usual. If China was able to cut its carbon intensity by 45 percent, the country would reduce the same amount of carbon emissions in 2020 from its baseline levels as it is required under the various ambitious 450 parts per million (ppm) of carbon dioxide equivalent scenario to keep the increase of global temperature below 2 C compared to the pre-industrial level. Clearly, the high end of China's target, if met, aligns with the specified obligation that China needs to fulfill under the 450 ppm scenario.

The previous two points clearly show that China's proposed carbon intensity target does not just represent business as usual as some Western scholars have argued.

Now let us see whether the proposed target is quite as ambitious as China argues. This involves assessing the issues of whether it is conservative and whether there is room for further increase. Arguably, China will claim to meet its carbon intensity target as long as it cuts its carbon intensity by 40 percent over the period 2006-2020. This raises the stringency issue of this proposed intensity reduction. The International Energy Agency estimates that national policies being considered in China would bring reductions of about 1 gigatons of carbon dioxide in 2020. This suggests a carbon intensity reduction of 43.6 percent in 2020 relative to 2005 levels, implying that the low end of China's carbon intensity target is conservative.

Is there room for China to increase its own proposed carbon intensity reduction of 40-45 percent by 2020? It would be hard, but not impossible. Given that many of the policies considered in the World Energy Outlook 2009 that will cut emissions of 1 gigatons of carbon dioxide in 2020 from its baseline levels are not particularly climate motivated, China could broaden such policies, speed up their implementation and enact additional ones, explicitly considering climate mitigation and adaptation. This would bring additional reductions in China's carbon intensity.

What then is the yardstick or upper limit on China's carbon intensity in 2020? One way is to base it on China's medium- and long-term energy conservation plan by the National Development and Reform Commission, the country's top economic planning and oversight agency. Such a plan sets up a quantitative energy-saving target for 2020, and requires that energy intensity be cut by 3 percent a year between 2003 and 2020. This suggests a reduction of China's energy intensity by 42.5 percent in 2020 relative to its 2002 levels.

Given China's increased energy intensity between 2002 and 2005 - which means China used more energy in 2005 than in 2002 to produce one unit of GDP - meeting this energy-saving goal under the medium- and long-term energy conservation plan requires that China's energy intensity be cut by more than 42.5 percent relative to 2005. Don't forget that this energy-saving plan was set when China faced much less severe environmental stress, energy security concerns and international pressure to take mitigation actions than it is now confronted with. This suggests that China should now aim for an even more ambitious energy-saving goal than was envisioned under the energy-saving plan set in 2004.

The author is a senior fellow at the East-West Center, Honolulu, and a professor at the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The opinions expressed in the article do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.