Drifting into reality

Updated: 2011-02-11 10:45

By Wang Yan (China Daily European Weekly)

A different drift

Ji Xiang, 27, drifted from one school to another for five years before achieving his goal of entering grad school. For him, grad school is not only "a way out", but it becomes a must given what he sees as society's blind belief in degrees.

He started drifting in 2004, just one year after being admitted to a local university in his hometown of Dongying, Shandong province. "I quit because the university and the major (engineering) were not good."

Ji then headed to Shandong University in Jinan and audited the classes of an English major.

|

He says his father strongly opposed his decision to drop out and sit in another class that doesn't guarantee a degree. "But I thought learning real knowledge is more important than getting an empty degree."

In late 2005, he drifted up to Peking University for better knowledge of international politics.

Like many other school-drifters, Ji settled in a cheapest place he could find, a 190 yuan-a-month bungalow near the campus. For living expenses, he depended on tuition refunds from the school he had left, plus part-time work as a tutor.

Free classes, though, were not easy to get, for the curriculum schedules are not open to public. Ji started by wandering the classroom building, sitting in every class he caught up with and noting the dates and places. In that way he made his own schedule.

"It was a busy and rich time. I listened to everything and almost became an expert in the field," Ji says, showing a smile with satisfaction. But he also realized that knowledge doesn't immediately reap what is needed.

"I tried to find jobs in the middle, but all I got by then was a vocational school-level degree," which he obtained by taking the country's exams for the self-taught. He says many of his ideal employers would not even look at his resume.

He then decided to get into grad school - but the country sets a bachelor's degree as a prerequisite for post-graduate exams. By the end of 2007, he completed the task by taking higher-level exams for the self-taught. And after a failed attempt in 2008, he finally became a grad student at China University of Petroleum, Beijing, in September 2009, majoring in international politics.

Ji is now in his second year and is interning in Beijing at ifeng.com, a news portal owned by Phoenix, a Hong Kong-based TV broadcaster. He says he wants to work in the media after graduation.

"It's like I've taken an indirect route," he says.

"I was kind of naive to think that simply acquiring knowledge would carve a niche for myself.

"In most cases, you've got to have a degree to fit into society."

[STORY CAN END HERE, FOR FIT. OR THIS SECTION COULD BE A LITTLE SIDEBAR IF THERE'S ROOM]

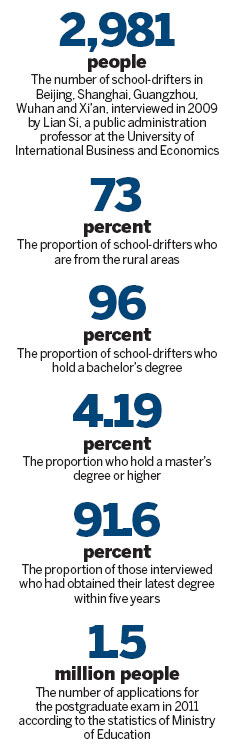

In 2009, Lian Si, a public administration professor at the University of International Business and Economics, interviewed 2,981 school-drifters in Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Wuhan and Xi'an.

"School-drifters are found from all over the country, except for the Tibet autonomous region. About 73 percent are from rural areas, and 82.9 percent don't hold a local hukou. About 96 percent hold a bachelor's degree, and only 4.19 percent hold a master's degree or higher," read the report.

Also, 91.6 percent of those interviewed had obtained their latest degree within five years.

Lian then concluded that the fifth year after graduation is a turning point, where most school-drifters would change their drifting lifestyle.

E-paper

Ear We Go

China and the world set to embrace the merciful, peaceful year of rabbit

Carrefour finds the going tough in China

Maid to Order

Striking the right balance

Specials

Mysteries written in blood

Historical records and Caucasian features of locals suggest link with Roman Empire.

Winning Charm

Coastal Yantai banks on little things that matter to grow

New rules to hit property market

The State Council launched a new round of measures to rein in property prices.