What makes us human

Updated: 2016-05-27 08:16

By Mei Jia(China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||

Pop-science author draws big audiences with his perspective on our species

Few historians receive the rock-star treatment when they give a talk on their latest book - but Yuval Noah Harari did.

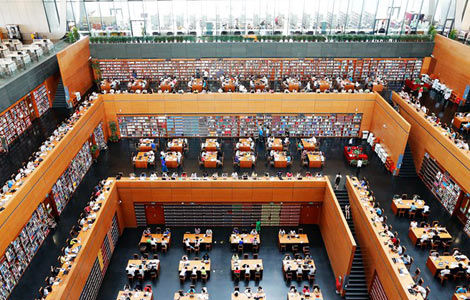

The 40-year-old Israeli enthralled an audience of about 2,700 at Beijing Expo Theater for almost four hours in late April when he spoke on Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. Another 140,000 paid to watch the live stream via the internet, too.

|

|

The book, currently No 74 on the Amazon best-seller list, is available in 43 languages, while high-profile fans include Facebook's CEO Mark Zuckerberg.

"It's my first time in China," he later tells China Daily. "I didn't expect (the response) and I was much impressed by the young people in the audience."

Shu Ting, editor of China CITIC Press and the show's organizer, says Harari's idea that early Homo sapiens differed from other animals due to their ability to create and believe in fictional realities has inspired many in China, including business leaders, scientists and young people.

"Money is a fictional story we're told, as well as empire, religion and more," Harari explains. "We believe money, a piece of paper, can be exchanged for a banana, but a chimpanzee won't. In this sense, bankers are better storytellers than Nobel literature winners."

Critics have said the historian's book is especially enlightening on internet startups.

Harari, a history professor with Hebrew University of Jerusalem, is himself a wonderful storyteller.

"It is important for me to communicate well with audiences in different countries," he says. "Examples are to make it easier for the readers to understand, and they need to be familiar to the reader."

He explains that he will change examples in his books to ensure understanding.

"I use Queen Elizabeth I as an example of powerful women to the English audience, and I use the Empress Dowager at the end of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) for the Chinese. Football in the British market, and basketball or baseball for the US," he adds.

Gao Yi, a history professor at Peking University, says she is absorbed by Harari's listing of historical events, but what impresses her most is his crossover on many subjects and realms of knowledge.

The book, which was initially turned down by five publishers in Israel, looks at human history over a period of 2 million years, covering three key revolutions - cognitive, agricultural and scientific - and one phase of human unification.

It was first published in Hebrew in 2011, and then in English three years later, when it received the China National Library's Wenjin Book Award.

To cover 2 million years in no more than 500 pages, Harari engages and connects ideas from biology, archaeology, politics, economy, genetics and artificial intelligence.

"History is complicated. To really understand it, you need to look at it from many angles at the same time and use multiple measurements," he says.

He also devotes a chapter to the subject of happiness, arguing that humans today are less happy than our ancestors, as we are filled with more desires.

Harari says historians seldom look at people's inner desire for happiness. However, his ideas have resonated with the Chinese readers' need for soul-searching.

"People don't make the most of the opportunities that their jobs offer them," he adds.

Harari specializes in medieval history and military history. But with experience and a secure professional position, he decided to be bolder and look at the bigger questions.

"The more you understand reality and your place, you can be much more calm and peaceful," he says, adding that he often walks in the woods and meditates two hours a day.

His next book, History of Tomorrow, will be available in English soon and later in Chinese.

Born in 1976 to an engineer father and secretary mother, Harari received his PhD from the University of Oxford in 2002.

"I was curious about big questions on why the world is the way it is and the deep forces that shape reality and our life, but didn't get satisfied with answers when young from parents and teachers. They seemed to be not interested in these questions," he recalls.

"Most people ask those big questions while young, but by 20-something, they put these questions aside, and think about practical issues. In my case, I just did not do that and they continued to be very central for me, from 14 to now."

meijia@chinadaily.com.cn

Q&A

'I see the world has many good things'

Are you pessimistic about our future?

I'm not a pessimist, and I'm trying to be realistic about the condition of the world and what we're to face. Pessimists try to find something wrong with every human invention and development. I'm not.

I see the world has many good things. This is the first time in history that humankind has managed to overcome famine. We also see a substantial reduction in violence. Previously, 10 percent of mortality was caused by human violence; today it is less than 1 percent.

But there are also problematic developments, like climate change and new technology that may get out of control, like artificial intelligence. In 30 to 40 years, most humans will have no job, their being taken over by AI. The biggest question in politics and economics in the 21st century is what to do with all those masses of "useless" people.

I'm afraid there is not enough attention given to these issues by government and the public. Governments are very busy with traditional problems. And it's the duty of historians and philosophers to understand present-day technologies, think about them in broader terms, and warn people of their risks.

What do you see in the future for China?

The future of China is also the future of the world. The future of the world is also the future of China. Today, there are no independent countries. China has no separate future from the other countries - it's all combined.

The major problems of humankind in the 21st century will all be global in nature.

Another positive development in China is that it's thinking in global terms instead of local terms.

You're living with your same-sex partner?

Oh, he's staying next door (in a Beijing hotel). He is my agent and accompanied me here.

Looking back, if something exists, it means it's part of nature. Not all things existing are good. If we're to judge, the question is not whether something is natural, but its impact on happiness and misery of living beings. It's not homosexuality that caused miseries. It's prosecution of it that caused it.

Today's Top News

Rescue vessel eyed for the Nansha Islands

Steeled for change

EU has to cope with outcome of British referendum

Four Chinese banks among world's 10 largest

Kiev swaps Russian detainees for Ukraine's Savchenko

Refugees relocated during major police operation

China calls for concerted anti-terror efforts

London's financial centre warns of dangers of Brexit

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|