In the hall of the great frescoes

Updated: 2016-04-15 08:52

By Zhao Xu(China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||

The nails are still there today, on a lower section of the northern wall in the main hall, together with a couple of holes that used to hold them. Yet in retrospect, the nail accident was far from being a real crisis.

Disaster averted

The last time Ding Chuantao, 82, visited Fahai Temple was in 2010. But between 1966 and 1981 the Chinese language teacher at Beijing No 9 Middle School lived on the temple grounds.

"The temple served as a dormitory for the school's male students from 1952," Ding says. "Then during the 'cultural revolution' (1966-1976), a political movement that had among its stated goals the crushing of everything considered feudal, began. Classes were soon ended as all students were gone. The temple became extremely peaceful, and it was a peacefulness that suited me well. I soon moved from my original housing down the mountain into one of the temple's side rooms."

That was the genesis of the friendship between Ding and Wu Xiaolu, the doorman of the middle school, whom many today consider the protector of Fahai Temple.

"On one occasion, a handful of teenage boys, aroused by the movement, rushed into the temple wanting to smash everything up," Ding says. "Realizing that the frescoes were more important artistically than the wooden Buddha sculptures that lined the frescoes' lower part, Wu made a painful yet quick decision. He said to the boys, 'Smash the sculptures if you want, but don't even try to put your hands on the frescoes before you smash me up.'"

The boys balked and the murals were saved. And according to Lu, the darkness inside the main hall also helped, since the vandals did not realize how sumptuous the frescoes were. She points out a horizontal line that goes through the 11-meter-long frescoes on both the eastern and western walls. It is about 60 centimeters from the bottom of the painting.

"The part above that line has been exposed for 600 years, while the part below it has been for 50 years, since the Buddha sculptures right in front of the walls were destroyed on that fateful day," she says.

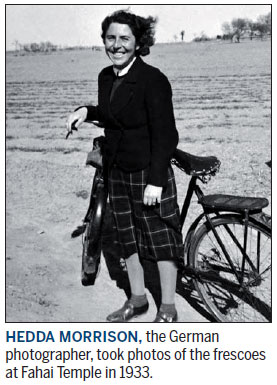

Today, those sculptures can be viewed only in the black-and-white pictures taken by British reporter Angela Latham, Morrison's contemporary, who photographed the temple in 1937 and had the pictures published in the Illustrated London News that same year.

Wu, in the final years of his life, suffered from Alzheimer's disease and handed the keys to Fahai's main hall to Ding. He died in the mid-1970s at age 74. "He never left the temple," Ding says.

Before his death, Wu, who had been an antiques dealer for years before a series of misfortunes brought him to Fahai, left a will in which he requested to be buried near the temple. The family obliged.

Lu saw the murals for the first time in 2011, before deciding that she "wanted to do something for them". Today, her faith is tightly bound to these murals.

Two big earthquakes

"There were two big earthquakes in Beijing, in 1679 and 1730. Fahai Temple was shaken, but the murals remained intact. It's true that time has done its worst. And at times in Fahai's history, the lack of maintenance has resulted in roof leaks and cracks in the murals. Yet if you examine the paintings inch by inch, as I have, you will see that never, not even once, has a major crack or rain mark passed across the face of a Buddha."

Lu, 55, believes that the frescoes' ultimate greatness resides in their power to move. "Step back and look into the eyes of the Bodhisattva, then walk slowly from her left side to right," she says, gesturing to me. So I do. And the goddess, looking down with her willow leaf-shaped eyes, never takes her silent gaze off me. Put another way, where I go, her eyes follow.

"See what happens?" Lu muses. "She's with anyone who's with her."

zhaoxu@chinadaily.com.cn

Today's Top News

Embryos growing in space a 'giant leap'

Russia to defend regional security jointly with China

Passage to piraeus

In the hall of the great frescoes

World Bank joins AIIB on financing for joint projects

GM seeds to get oversight

Russia-China ties benefit both countries, peoples

China, UK showcase best books in London

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|