In the hall of the great frescoes

Updated: 2016-04-15 08:52

By Zhao Xu(China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||

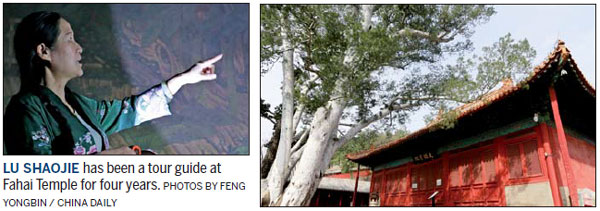

Commissioned by eunuch

Few, according to Lu, have dug deep into the history of the frescoes, and by extension that of the temple. Built between 1439 and 1443, Fahai Temple was commissioned and funded by Li Tong, a powerful eunuch of the Ming who is believed to have served five successive emperors. History shows Li built the temple to express his gratitude for royal favor. Artists were recruited from all over China and worked under the supervision of the most celebrated court painters of the day, among whom 15 had their names inscribed in a stele placed inside the temple.

The result of the five-year endeavor is a grand temple built on three terraces and scaling Cuiwei Mountain. The original design featured a main hall and four ancillary halls, as well as a bell and drum tower and several side rooms. Today, the main hall is the only building that has survived, the others being reproductions. And the frescoes inside are the sole reminder of the length all those involved went to in order to create this ultimate tribute to Buddha, and to the Ming emperors who were among the Buddha's most powerful worldly followers.

Covering 237 square meters in total, the frescoes include 77 figures - not including animals - in nine scenes that amount to either individual or group portraits. The tallest one is 2 meters high and the shortest 50 centimeters.

A detail Lu never fails to point out to visitors is the white gauze draped across the body of Avalokitesvara, or Bodhisattva, the Goddess of Infinite Compassion, painted on the back wall of the altar. The flimsy piece of clothing is made up of little hexagonal flowers, each petal measuring less than 1 square centimeter, composed of eight veins.

"The brush used for this purpose must have no more than three hairs," says Lu, referring to the fluidity and cloudiness of the fabric that would be lost if viewed up close. "Such meticulousness can only be fully appreciated when the viewer is looking at the subject from a distance."

However, the status that the murals enjoy today in Chinese art history has not protected them from vicissitudes, especially in modern times. By the late 19th century the temple compound had been reduced to an ad hoc refugee camp, colonized by paupers. The temple, once a popular pilgrimage site, gradually fell into disrepair, a state in which it remained during the tumult of the first half of the 20th century, until spring 1950, the year following the founding of the People's Republic of China.

"In the spring of 1950, some artists who had heard about Fahai went there to paint," says Tao Jun, deputy director of the Fahai Cultural Relics Bureau. "There they discovered, to their great horror, iron nails driven into the walls of frescoes. It turned out that soldiers stationed there had used the nails as clothes hangers."

The alarming message was soon passed to a respected art professor at the Central Academy of Art in Beijing. It did not take long before it reached other important cultural figures and, ultimately, the Beijing municipal government, which alerted the army.

"Any further damage by unmindful soldiers was stopped," Tao says. "Fearing that pulling out the nails might cause more destruction to the wall, they were allowed to stay."

Today's Top News

Embryos growing in space a 'giant leap'

Russia to defend regional security jointly with China

Passage to piraeus

In the hall of the great frescoes

World Bank joins AIIB on financing for joint projects

GM seeds to get oversight

Russia-China ties benefit both countries, peoples

China, UK showcase best books in London

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|