A handmade digital effect

Updated: 2011-12-27 11:10

By Wen Chihua (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

|

|

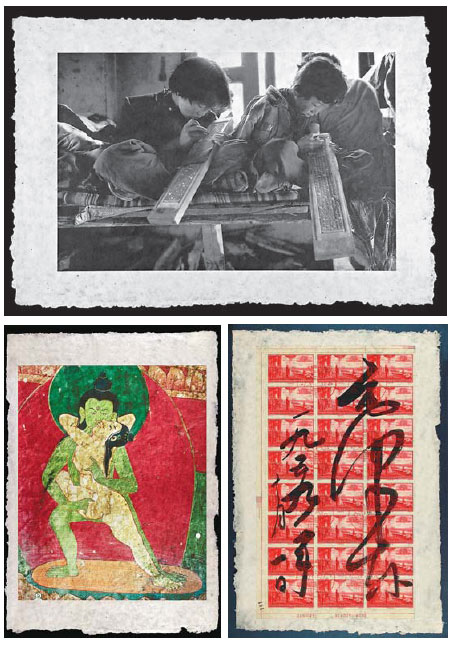

Combining modern inkjet technology and a kind of Tibetan paper, Jin Ping recreates two Tibetan thangka. Photos Provided to China Daily |

|

|

Clockwise from top: Youngsters study traditional papermaking at the Dege Sutra Printing House. One of Jin's representative works is the recreation of commemorative stamps, from 1959. Jin's recreation of a painting from Tibetan Buddhist sutras. |

The 1,300-year-old Tibetan paper makes an image look like it is mysteriously illuminated and is, therefore, the ideal medium for photographer Jin Ping. Wen Chihua reports.

Photographer Jin Ping is not obsessed with technology - but he has long been charmed by the exploration of new methods of image presentation.

The Chengdu, Sichuan province-based photographer, who is in his 50s, has succeeded in developing a distinctive method of combining modern inkjet technology and a kind of Tibetan paper that has a 1,300-year history.

The hybrid process makes the image appear like "a musical charm and a mix of originality and modernity", Jin says.

One of the most intriguing pieces Jin has created with this new method is a recreation of a plate of 24 commemorative stamps issued in 1959 to mark the 10th anniversary of the founding of New China.

The original monochrome woodcut stamp features Chairman Mao Zedong in a dark green uniform, standing on the Tian'anmen Square rostrum as he proclaims the founding of New China.

In Jin's representation, the powerful Mao looks warm and graceful. The fiber of the Tibetan paper creates a surface texture with complex characteristics that subdues the sharpness of Mao. The paper's rough grain makes the simple colors look rich but not exaggerated.

This work deeply impressed the British stamp collecting community, and they invited Jin to create two pieces. One is a reproduction of a plate of 12 Penny Black stamps, the world's first adhesive postage stamp used in a public system. The other is a recreation of the Penny Black's sister stamp, a plate of the 18 Penny Red stamps.

Printed on Tibetan paper, the work lends an Eastern flavor to Queen Victoria's profile image.

Jin's exploration of Tibetan paper started in 2006 when he went to Dege Sutra Printing House in Garze Tibetan autonomous prefecture, Sichuan province.

At the printing house, one of the things that Jin discovered was that the techniques of writing, carving and block printing have remained largely the same as they were in the 13th century. And the tradition of Tibetan papermaking has been passed down for centuries.

"It is a priceless living example of folk craftsmanship," Jin says.

Jin, who had worked in the printing industry for more than 10 years, says, "Tibetan paper makes an image look like it is mysteriously illuminated. I realized this age-old medium would be able to create an unexpected visual effect for digital images."

Tibetan paper is noted for being clean, mothproof and moisture-proof, and possessing a long shelf life. Tibetan Buddhists use it to print classic sutras, which can stay in perfect condition for hundreds of years.

The paper is made of the root hair of the Stellera chamaejasme plant, a medicinal herb referred to as Agyiaorugyiao. The plant, which grows about 3,000 to 4,000 meters above sea level on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, is toxic, germicidal and antiviral.

"Because the paper is fully handmade, every sheet is unique, making it an ideal medium for contemporary art creations," Jin says.

For the past few years, Jin has traveled deep into Southwest China, exploring the disappearing craftsmanship of traditional papermaking in remote ethnic areas.

He has tested various kinds of techniques and adopted giclee printing (printing fine art digital prints on inkjet printers) to print his photos on the handmade papers of six ethnic groups, including Tibetans, and the Dai, Miao and Bai ethnic groups.

"These papers all have a wonderful ability to enhance the expression of the artist," Jin says. "However, I favor Tibetan paper. It gives the image an extremely profound, touching and warm expression."

Filled with inspiration acquired from Dege Sutra Printing House, Jin reconfigures a traditional medium with 21st century eyes. He launched a quiet revolution in his studio in Chengdu to connect the sutra paper with modern micro-dispenser technology. It took him more than half a year just to get the inkjet machine to print the way he required.

Unlike standard industrial paper, Jin says, every page of handmade Tibetan paper has an uneven character. "Without the fixed memory, the machine doesn't know where to start printing an image."

Jin's endeavors paid off. His Dege: Impressions, a series of pictures documenting Tibetan papermaking, sutra woodblock engraving and the classic Buddhist printing process, produces images that appear unsophisticated yet clear.

In his private life, Jin smokes Cuban cigars, enjoys fine tea and keeps vintage wines in his cellar. In his work, he is compassionate and highly respected.

In 2007, he took part in a national project to rescue traditional cultural practices. He led a team to Palpung Monastery in Garze to photograph thangka - Tibetan silk paintings that usually depict a Buddha, a famous scene, or a mandala, and are often embroidered.

When Jin and his team arrived in Garze, they stayed in the village at the foot of the mountain for a week without getting approval to photograph in the monastery. While he was waiting, Jin noticed the children in the village were poorly dressed. He donated 60,000 yuan ($9,469) to buy clothes for the youngsters.

His actions moved the parents and the lamas of the monastery, who believed Jin was a photographer with a benevolent heart. They granted him permission to shoot inside the monastery.

The thangka in the monastery are historically significant. They were created during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). The thangka framed in Jin's photos have only been seen by the public three times.

The first time was for local Buddhists when the paintings were completed. The second was during the "cultural revolution" (1966-1976). In order to prevent the thangka from being destroyed, the monastery had them numbered, registered and stored in the homes of local Buddhists. The third time was for Jin.

Jin had the thangka photographs digitized, and printed on Tibetan paper. The visual effect of the process shows the luster of the thangka and the delicate nature of their original creation.

Jin keeps an abundance of Tibetan paper in storage. He is concerned the paper may disappear from the market in the future. He is also helping Dege Sutra Printing House preserve the tradition of papermaking.

In Dege today, there are just six artisans who have mastered the craft. They make just 600 sheets annually.