Threads of tradition

Updated: 2011-12-20 08:05

By Zhou Wa (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

|

An artisan hands in her hand-made scarves to Aqi Duzhima (right) in Walabie village, in Lijiang city's Ninglang county, Yunnan province. Photos by Zhang Yi / For China Daily |

The mechanization of Mosuo scarves by outsiders threatens the group's heritage and livelihoods. But villagers remain hopeful. Zhou Wa reports.

Aqi Duzhima often visits the unused land behind her house - a place the 47-year-old Mosuo woman calls the "land of my dreams". She won't plant any crops on this swath of earth in the remote village of Walabie, in Lijiang city's Ninglang county, Yunnan province. Instead, she plans to build a factory manufacturing the Mosuo scarves local villagers have created for generations.

Duzhima will sell them in the big cities and bring back the money to the inhabitants of her secluded mountain village - exactly as she has done for years, before outsiders built factories to mass produce the scarves, essentially pushing Walabie's people out of the market.

Duzhima's plan is still just a dream.

She faces a lack of business savvy, investment, resources and experience. Still, she and her son Aqi Nimacier, the first villager to study business in college, are pushing ahead.

Duzhima began weaving scarves with traditional Mosuo looms in 1993.

After years of hard work, she helped villagers improve their incomes through selling the scarves. They gave Duzhima the scarves, and she sold them to vendors in Lijiang and gave the profits back to the families.

But some modern factories caught on to the marketability of Mosuo scarves and started mass-producing them. The manufactured scarves were cheaper and easier to make, so vendors started buying from the factories rather than the villagers.

Consequently, Duzhima's storehouse is crammed with surplus handmade scarves.

Nimacier puts it this way: "The best weavers can produce about 20 scarves a day, while one machine can make 200."

"So our handmade scarves will never be able to compete."

|

The mother and son find it difficult to sell to the outside world from their isolated village. It takes eight hours to reach Lijiang, the nearest city.

"People in our village have been isolated in the mountains around Lugu Lake for generations," Nimacier says.

"Most of us have never left Walabie. How can we know what's in fashion in big cities? That's not to speak of consumers' needs."

But that's just one of their problems, he says.

"If we had more money, we would buy better raw materials. Now we can only afford those left over by modern textile factories."

And using inferior materials has increased defects in their handmade scarves.

Some of Walabie's households have abandoned scarf weaving to search for other ways to earn a living.

Bajin Duma's family, for instance, sells herbs.

"We used to sell herbs," Duma's grandfather says. "We got back into the business when it became difficult to sell scarves."

While Duzhima and Nimacier both hope to revive the sector by opening the factory, they disagree on parts of the plan.

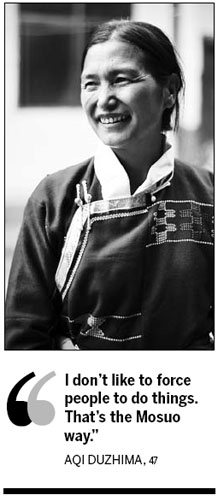

Duzhima doesn't set quotas or deadlines for weavers.

"I don't like to force people to do things," she says. "That's the Mosuo way."

But Nimacier disagrees.

Still, the mother and son remain committed to opening the factory despite different views on its operation.

"What's the good of doing nothing but crying?" Duzhima says. "Do something practical to change your situation."

Duzhima remains optimistic.

"I believe what we are doing is meaningful," she says. "We can make it, eventually."

Nimacier registered Walabie's scarves' trademark in his mother's name in 2009.

"My mother is one of the inheritors of Mosuo weaving, which is listed as a national intangible cultural heritage. So her name will surely add value to our scarves," he says.

And Nimacier, too, has continued studying weaving techniques.

"We must add some unique elements to our scarves and create our own competency," he says.

The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and its partners have offered to help Duzhima and her son with an initiative to alleviate poverty in regions inhabited by poor and vulnerable ethnic groups. It will mainly provide technical and institutional support and guidance to start and maintain successful business models.

The UNDP and partners will not only offer the Mosuo people financial support, but also address challenges. Such challenges include discovering how to meet consumer demand for authenticity while also producing on a commercially viable scale, and how to adapt traditional designs to modern tastes without losing cultural uniqueness.

"By providing soft skills training, we would like to encourage and teach the people how to fish, instead of giving them fish through our initiative," UNDP project manager Pei Hongye says.

"So, it is important that the local people themselves have the will and determination to develop. We know Duzhima and her son have both, and we encourage them to carry on their efforts. We believe they will set a good example for the local people."

Some experts believe that, even with the UNDP's assistance, the undertaking remains problematic.

"The UNDP's and its partners' guidance is undoubtedly good," Yunnan Academy of Social Sciences scholar Sun Dajiang says.

"But the question is how the Mosuo people undertake the venture practically. And it takes time to go from the development of skills to the production of results."

But the UNDP and mother and son believe obstacles can be overcome.

"Although it will take time to show results, we have gathered a lot of experience on transforming skills training into real development results through our past programs," Silvia Morimoto, UNDP's deputy country director in China, says.

Nimacier also knows challenges persist despite UNDP help.

"But I believe what we are doing is meaningful, so we can make it, eventually," Nimacier says, gazing at the prospective factory site.

"If my mother and I cannot make our dream come true, my children will."

|

A Mosuo woman in Walabie village weaves according to tradition. |