Adventures in words

Updated: 2011-11-18 10:44

By Mei Jia (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

|

|

Huang Nubo has scaled the highest summits of all seven continents, and reached the north and south poles. Provided to China Daily |

Scaling the world's highest mountains propels the prose of Huang Nubo to soaring heights. Mei Jia reports.

Huang Nubo has multiple identities - as a businessman, adventurer and a writer. But the 55-year-old Beijing-based Zhongkun Investment Group Co Ltd chairman says he's first and foremost a poet. It's that prose-fueled drive that has propelled him to ride over the hardships of running his company and surmount the world's highest mountains. His writing career reached its greatest heights this May, when he stood at the apex of the world's highest peak, Qomolangma (known as Mount Everest in the West), and read aloud his new creation, Qomolangma, In Tears I Say Farewell to You.

Huang has scaled the highest summits of all seven continents, and reached the north and south poles, during a total of 20 months of expeditions from 2008 to 2011. The undertaking is known as the "7+2" project.

Huang is the 15th adventurer to conquer the challenge since Russian adventurer Fedor Konyukhov devised and completed the route.

|

He always brings pens and notebooks on his sojourns and jots down poems as he sits on the plane or atop a towering alp.

"I always end up with ink-stained hands, because pens leak in the low pressure of high mountains," he says.

Peking University Press published about 300 of his poems under his penname Luo Ying in the collection 7+2 Mountain-Climbing Diary in early November.

Huang hopes the book becomes a trendsetter, and relishes life and the Chinese language, which he believes contemporary prose fails to do.

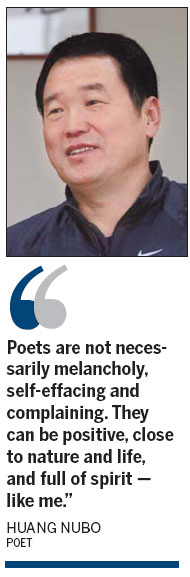

"Poets are not necessarily melancholy, self-effacing and complaining," Huang says.

"They can be positive, close to nature and life, and full of spirit - like me."

Beijing poet Bei Ta compares Huang to American writer Ernest Hemingway because of his tough-guy image and approach to literature.

Huang puts it this way: "I climb to write poetry."

It was curiosity that led him to take on his first ascent in 2005, and every expedition since has been to provide inspiration for his writings.

He is moved by mountaineering's views and challenges, which he finds to be in stark contrast to the "restricted" and "vulgar" city life.

"Everything looks like a painting when you're 8,300 meters above sea level," he says.

Huang recalls one night spent convulsing alone halfway down a snowy mountain, unable to seek help. He eventually gave up resisting and decided to see what his illness would do with him. It eventually released him, and he continued his expedition.

Critic Lei Shuyan explains Huang's poems even cover topics like excrement.

"Huang writes with extreme freedom and passion, and sees the grandeur of the trivial," Lei says.

Some critics say the collection is an easy and fun read at the beginning that gets heavier and more serious - a metaphor for the weight of life and human willpower.

"We seldom see poems about the themes Huang covers in the collection," critic Hu Xudong says.

"It's educational and explores poetic extremes with romanticism."

Another of Huang's ambitions is to revive writing in authentic Chinese, rather than the tones of modern poems, which have been inspired by the Western literature craze that started in the 1920s and was revived in the '70s and '80s.

"Chinese poems have a unique system of imagery, vocabulary, colors, rhythm and rhetorical skills that stems from a longstanding tradition," he says.

"Those are iconic things that won't be lost even after translation into other languages."

|

Huang has been creating poems for more than four decades, starting when he was orphaned at age 13.

He writes about love, youth and competition, and about rural and urban life. His many collections have been published and translated into several languages.

Huang wrote about his childhood miseries; the sparkling years he spent studying at Peking University; working as a young government official after graduation; and the setbacks and successes after he quit his "steady" job.

He recalls being laughed at when he told a gathering of leading entrepreneurs, "I'm a poet."

Huang believes people today myopically focus on materialism and entertainment.

"It's not an era for great writers," he says.

"But it's worth it to try to bring that era about."

Huang still believes contemporary poetry has an audience. He has spent vast sums of money to sponsor universities and international poets exchanges.

"Nowadays, people don't talk about ideals," he says.

"But I believe poetry is the solution. Rich or poor, a poet should have ideals. That's what has gotten me through every hardship."