The Dead Sea Scrolls, and what came before

Updated: 2011-11-13 07:00

(The New York Times)

|

|||||||||

|

A New York exhibit featuring fragments of the Dead Sea Scrolls offers a new historical arc for the parchments. [Tina Fineberg for The New York Times] |

Few artifacts at the provocative new exhibition at Discovery Times Square in New York - "The Dead Sea Scrolls: Life and Faith in Biblical Times" - will inspire aesthetic wonder. Pottery, silver coins, iron arrowheads, limestone pitchers, scraps of parchment - such are the seemingly mundane yields of many archaeological excavations, and they are prevalent here as well.

And while there is some attempt at spectacle - when an actor welcomes you into a gallery showing stunning scenes of the Dead Sea, or when you descend a staircase and see 10 fragments of the scrolls dramatically arranged in a rotunda - this exhibition's real enticements lie elsewhere. They come not from objects, but from connections among them; not from stunning displays, but from intellectual vistas.

|

|

The artifacts are drawn from archaeological explorations by the Israel Antiquities Authority. Some have been recently found; some are being shown for the first time. This is, we are told, one of the largest such exhibitions ever organized. But the main interest of the show is in the historical arc.

The narrative treats the scrolls not as the beginning of a history, but as its culmination. This is almost the reverse of their usual treatment. Since the first scrolls were found by Bedouins in 1947 in caves near the Dead Sea, they have inspired extraordinary drama and debate.

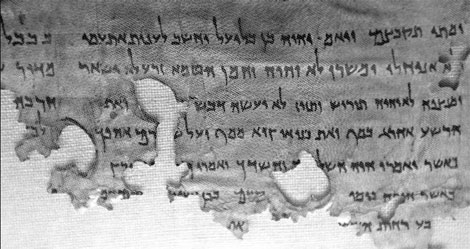

Before their discovery, the earliest known texts of the Hebrew Bible were from about 1,000 years after these scrolls were written. In the caves were over 800 scrolls and fragments, including Hebrew biblical texts before they were canonized, all written during a 200-year period of ferment in which the Israelite religion was about to be shattered by exile in A.D. 70, as Christianity was emerging.

Excavations of a site near the caves - Qumran - have suggested that a religious community lived there during the period when the scrolls were written, perhaps in the first century B.C. One hypothesis about Qumran was that its inhabitants were Essenes or proto-Christians, and that the scrolls describe the first stirrings of that new religion, evident in their messianism and references to the "Son of God." This view became orthodoxy as a small group of scholars retained control over many scrolls for almost 40 years.

During the last two decades, though, the debate has become more diverse, as the scrolls have been made available. Hypotheses proliferate. What was Qumran? A fortress? Pottery factory? Repository for the Jerusalem temple's library? Were the scrolls written by Qumran scribes?

The exhibition avoids conclusions. Instead it ends with a kind of ecumenism, referring to how modern Judaism and Christianity evolved out of the texts of ancient Israel and how Islam, too, grew out of these narratives.

But the show as a whole is more interested in the scrolls' past. We see the scrolls only after we have walked through a chronicle of the region's milestones, illustrated by archaeological finds in the collection of Israel National Treasures. And they position the scrolls not just as a part of religious history but also as a part of national history.

This is a reason that the exhibition, which is on view through April 15, establishes a parallel between the devotional fervor of the Qumran community (destroyed by the Romans in A.D. 68) and the zealotry of rebel holdouts at Masada, a cliff settlement overlooking the Dead Sea (destroyed by the Romans in A.D. 73).

Displays about both communities include potsherds, seeds and dried fruit. There are ropes from Qumran and wool textiles from Masada.

The flaw is that we never really comprehend how such a religious culture and its scrolls evolved out of this history. But we do see a history exceptional in its traumas and influences.

In this sliver of land, the curators explain, "the beliefs and material culture of locals, nomads and invaders have intermingled for millennia."

The New York Times