The history of everything in 100 things

Updated: 2011-11-07 11:09

By Carol Vogel (The New York Times)

|

|||||||||

|

|

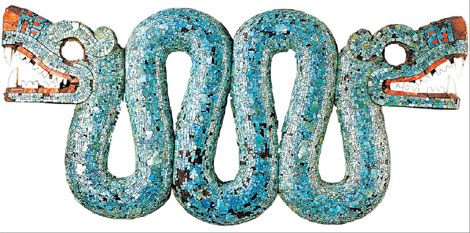

Double-Headed Serpent Aztec Figurine From Mexico (A.D. 1400-1600) Made of about 2,000 small pieces of turquoise set on a wooden frame. |

London

From The British Museum, the stuff that defines us.

It was a project so audacious that it took 100 curators four years to complete it. The goal: to tell the history of the world through 100 objects culled from the British Museum's sprawling collections. After four years, the result was unveiled on a BBC Radio 4 program in early 2010. The program was so popular that the BBC, together with the museum, published a hit book of the series, "A History of the World in 100 Objects," which was published in the United States on October 31.

Other museums might be inspired to invent variations on the "100 Objects" theme, but none can match the breadth of collections at the British Museum. And its holdings don't include paintings, unlike other institutions with comprehensive collections like the Metropolitan Museum of Art or the Louvre.

"In all other museums European pictures overrule the rest of the collection," said Neil MacGregor, the director of the British Museum. "We are the only one of these encyclopedic museums where Europe is not dominant in the narrative. That's a huge advantage if you're trying to make sense of the world today."

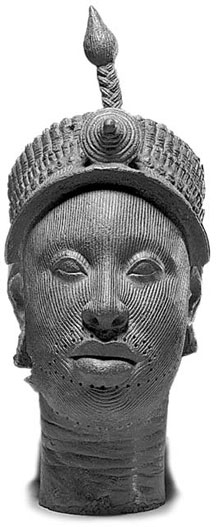

Head of IFE

Brass statue from Nigeria (A.D. 1400-1500) "It is one of a group of 13 heads, superbly cast in brass, all discovered in 1938. ... They embody the history of an African kingdom that was one of the most advanced and urbanized of its day."

|

|

Head of IFE Brass statue from Nigeria (A.D. 1400-1500) "It is one of a group of 13 heads, superbly cast in brass, all discovered in 1938. ... They embody the history of an African kingdom that was one of the most advanced and urbanized of its day." |

Discussing David Hockney's 1966 etching of two men lying in bed side by side, Mr. MacGregor notes, "It raises perplexing questions about what societies find acceptable or unacceptable, about the limits of tolerance and individual freedom, and about shifting moral structures over thousands of years of human history."

The final object chosen was a plastic, solar-powered light the size of a coffee mug that came with a charger and cost $45. It can illuminate a room, enough to change the lives of a family with no electricity.

"It is a transformative object, one that sets people free," Mr. MacGregor said. "Once they have access to solar power, they have access to the Internet, then they have access to the world of knowledge."

The idea for the project was hatched after Mr. MacGregor had narrated some radio programs for the BBC about specific items in the museum's collections, and they had received a surprisingly enthusiastic response.

In the beginning, he said, the underlying mission was to find a way for visitors to make sense of the museum's vast holdings by taking a single object and putting it into a larger context, one that told a story that everybody could relate to. "It became this fascinating balance between the chronological and the geographical and the thematic," he said.

Objects were grouped under intriguing chapters: "Empire Builders," "Inside the Palace: Secrets at Court," "After the Ice Age: Food and Sex."

Often the tiniest things make the loudest statements. Take, for example, an Edwardian penny defaced with the words "vote for women," or a five-centimeter-square ivory label once attached to sandals belonging to one of the earliest Egyptian pharaohs.

Museum officials say there have been 24 million downloads of segments from the BBC's Web site; the book was a best seller.