Chinese scientists create functional sperm from stem cells in lab

Updated: 2016-02-26 10:13

(Xinhua)

|

|||||||||

|

|

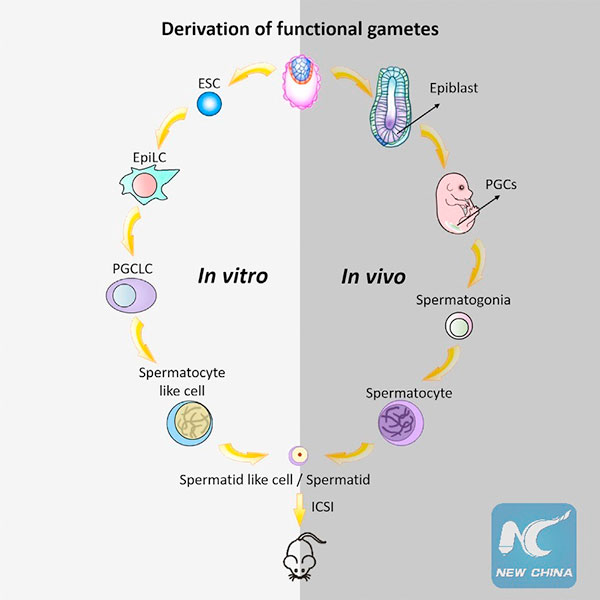

This graphical abstract shows how Zhou et al. generated haploid male gametes from mouse embryonic stem cells that can produce viable and fertile offspring, demonstrating functional reproduction of meiosis in vitro.[Photo/Xinhua] |

WASHINGTON - Scientists from China said Thursday they have finally succeeded in creating functioning sperm from mouse embryonic stem cells in the laboratory, a major scientific development that could some day lead to a treatment for male infertility in humans.

The researchers, who described their groundbreaking technique in the U.S. journal Cell Stem Cell, then successfully used the functional sperm cells to produce healthy mouse offspring, which went on to give birth to the next generation.

"We established a robust, stepwise approach that recapitulates the formation of functional sperm-like cells in a dish," co-senior study author Jiahao Sha of Nanjing Medical University said in a statement. "So we think that it holds tremendous promise for treating male infertility."

Co-senior study auhtor XiaoYang Zhao of the Institute of Zoology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, however, noted that before this technique is translated to the clinic, possible risks and species differences between mice and humans must be fully studied.

"Therefore, it's too early to discuss the technique's clinical use now," Zhao said in an email to Xinhua.

Infertility affects up to 15 percent of couples, and about one-third of cases can be traced to the man.

One major cause of male infertility is the failure of precursor germ cells in the testes to undergo a type of cell division called meiosis to form functional sperm cells, the researchers said.

Several studies have reported the successful generation of precursor germ cells from stem cells, but the precursors then had to be injected the tests of sterile mice in order to create mature sperm.

In the new study, Sha teamed up with co-senior study authors XiaoYang Zhao and Qi Zhou of the Institute of Zoology to develop a stem cell-based method that fully recapitulates meiosis and produces functional sperm-like cells.

The first step was to expose mouse embryonic stem cells (ESCs) to a chemical cocktail, which coaxed the ESCs to turn into primordial germ cells.

Next, the researchers mimicked the natural tissue environment of these precursor germ cells by exposing them to testicular cells as well as sex hormones such as testosterone.

Under these biologically relevant conditions, the ESC-derived primordial germ cells underwent complete meiosis, resulting in sperm-like cells with key features of meiosis, including correct nuclear DNA and chromosomal content.

Finally, the researchers injected these sperm-like cells into mouse egg cells and transferred the embryos into female mice and found these embryos developed normally and gave rise to healthy, fertile offspring.

In future studies, the researchers planned to test their approach in other animals such as primates in anticipation of human studies.

"If proven to be safe and effective in humans, our platform could potentially generate fully functional sperm for artificial insemination or in vitro fertilization techniques," Sha said. "Because currently available treatments do not work for many couples, we hope that our approach could substantially improve success rates for male infertility."

Several U.S. experts, including Professor Kyle Orwig of the University of Pittsburgh, Assistant Professor Vittorio Sebastiano of the Stanford School of Medicine and Professor Peter Donovan of the University of California, Irvine, who were not involved in the study, called the results "landmark," "a milestone in the (stem cell) field" or "a significant advance" in understanding sperm development and production.

These experts also said they thought that the technique could be adapted in the future using induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), which act much like embryonic stem cells but are created from skin cells, in order to circumvent most of the ethical concerns related to the requirement to use embryos.

"Someday and under some circumstances, germline gene therapy might gain acceptance," Orwig said in a statement. "If that occurs, iPSCs (not ESCs) could be an outstanding vehicle for correcting infertility-causing genetic defects before differentiation to germ-like cells."

Today's Top News

Beijing edges NYC as home to most billionaires

110,000 refugees, migrants reach EU by sea in 2016

Tech giants reveal 5G innovations in Barcelona

Mechanism to be built to monitor ceasefire in Syria

London mayor says to support Brexit in EU referendum

What ends Jeb Bush's White House hopes

UK to hold EU referendum on June 23

US saber-rattling could spark arms buildup: experts

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|