UK scholar tuned into China's WWII resistance

Updated: 2015-04-08 07:02

By Cui Shoufeng(China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

This is the second in a series of special reports about the experiences of foreigners who either lived or served in China between 1937 and 1945. Here, a photo exhibition is shedding light on an economist, radio expert who aided guerrilla forces, Cui Shoufeng reports.

Michael Lindsay arrived in China in 1938 intending merely to teach Keynesian economics. Instead, he was inspired to play a crucial role in the country's resistance against the invading Japanese forces.

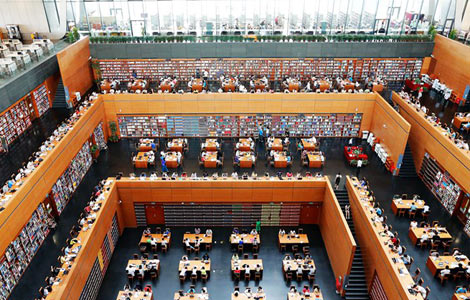

The Englishman, now the subject of a photographic exhibition that has visited several Chinese universities, helped to smuggle vital supplies to guerrilla fighters during World War II and spent years behind enemy lines, where he even started a family.

|

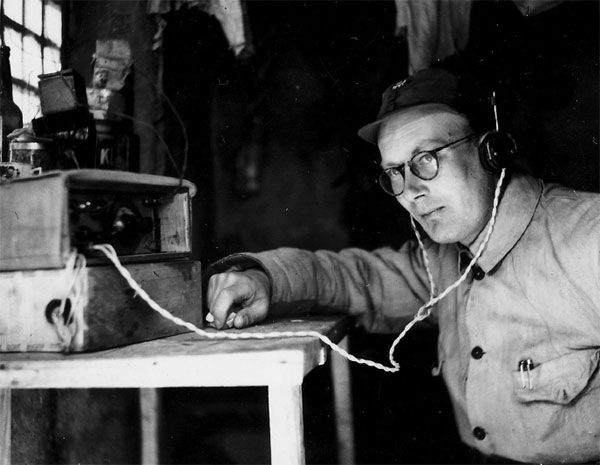

Michael Lindsay tunes a radio receiver at the Jinchaji base in Hebei province sometime between 1941 and 1944. Provided to China Daily |

|

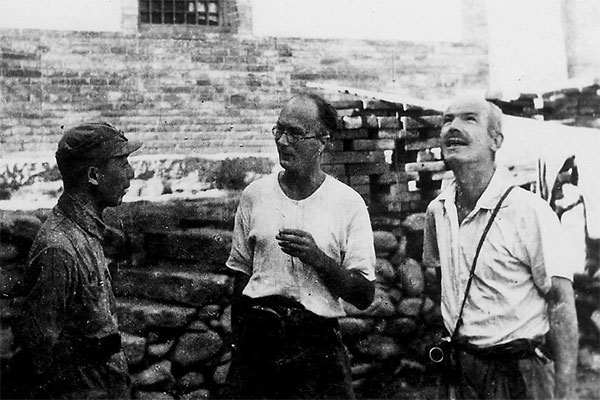

Marshal Nie Rongzhen (left) talks to Lindsay (center) and Norman Bethune on Aug 6, 1939. |

|

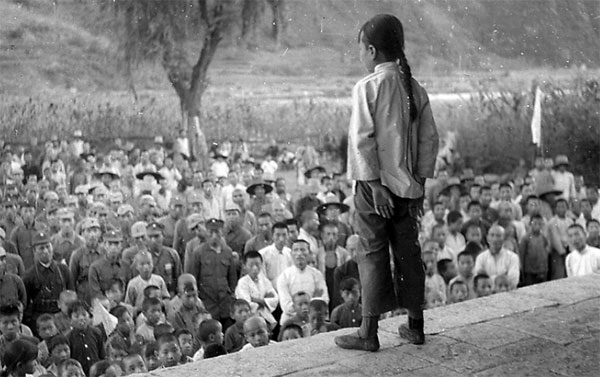

The head of the Children Resistance Regiment attends a public gathering in Pingxi, 1939. |

|

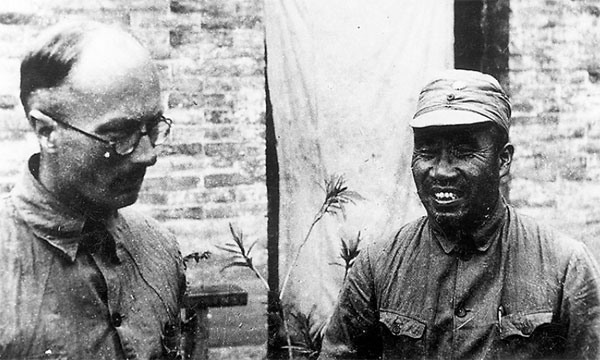

Marshal Zhu De (right) talks to Lindsay in Zhu's headquarters in late September 1939. |

War had already broken out by the time Lindsay, an Oxford College graduate and former student of groundbreaking economist John Maynard Keynes, arrived in Beijing to take up a lecturing post at Yenching University, later renamed Peking University.

The Japanese imperial army's invasion of northern China began in July 1937, and three months later the first village massacre was reported in nearby Hebei province, then known as Hopei.

In the occupied Beijing, Lindsay had become "distressed by his students' stories of the way they were treated by the Japanese police at the city gate", his granddaughter, Washington-based scholar Susan Lawrence, said in December when the exhibition opened at Shanghai Library before moving to Beijing's Peking University and now Renmin University of China, which hosts the show until April 17.

Her grandfather also witnessed firsthand appalling actions by the occupying forces, she said.

The economist was just 28 at the time, yet he was forced to make a life-or-death decision: flee the country or join the fight.

In the spring on 1938, Lindsay learned of a resistance movement forming outside Beijing and, at the first opportunity, traveled with some colleagues to the communist-led Jinchaji base, named after the area straddling Hebei and Shanxi provinces.

Inspired by what he saw, he returned to the capital and began to help the guerrilla forces in his spare time by sending supplies through secret channels, the most important of which were medicine and radio parts.

Due to his foreign appearance, "although the occupation troops might have had their eyes on this young Englishman, they couldn't search him at the city gates like they did to all the locals", according to professor Tonglin Lu at Shanghai Jiao Tong University's School of the Humanities, an authority on foreigners involved in the Chinese resistance during World War II.

He enlisted the help of one of his students to relabel in Chinese the items he bought, to avoid the stores where he purchased them facing any backlash if Japanese soldiers ever intercepted a shipment. That student was Li Hsiao Li, who later became his wife.

Li was the daughter of a retired army colonel and had intended to study in Nanjing, capital of Jiangsu province, before the Japanese invasion forced her to change her plans and gain admission to Yenching University.

Radio expert

The surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, which led to the United States declaring war on Japan, meant Lindsay's face no longer protected him from the occupying army. His "part-time career" as a smuggler at an end, the economist and his new bride (they wed in the summer of that year) left Beijing for the Jinchaji base.

There he became a full-time radio technician for the armed farmers fighting an arduous war for their freedom and their homeland.

"As an amateur radio technician, my grandfather was always able to use limited resources to rebuild wireless setups without complaining about the supply shortage," Lawrence said.

To improve communication with other resistance forces in northern China, Lindsay tinkered with the radio sets at Jinchaji to make them significantly more powerful and reliable, and made them easier to carry around over rough terrain.

Good communications were crucial for sharing intelligence about the enemy's movements and dodging incoming attacks.

Annoyed by the fact that the world - even southern China - knew hardly anything about the active resistance in the north, Lindsay offered his expertise to Yan'an, the Communist Party's central base in Shaanxi province, to boost its communication with the outside.

Thanks to a larger transmitter and a directional aerial that Lindsay built, professor Lu said, the Yan'an-based Xinhua News Agency was able to send reports to decision-makers in Washington.

"Xinhua's radio broadcasts were of interest to Washington," she explained. "It wanted to know more about the Japanese deployment and operations in northern China."

In the meantime, Lindsay also put his scholarly skills to use. He wrote personal notes and took photographs, shared his opinions with overseas contacts, and passed advice and criticism to leaders of the resistance, including Marshal Nie Rongzhen, the top commander at Jinchaji, and Qin Bangxian, the director of Xinhua News Agency.

In his reports to the US and British embassies and outside newspapers, he wrote about what he saw in Jinchaji and Yan'an. He said he believed the rampant atrocities by the Japanese invaders could only motivate more people in northern China to join the communist-led resistance.

Securing success lay not only in the guerrilla's military capabilities, he said, but more important in the ability to mobilize the masses. He predicted that the organized Chinese peasants could claim victory, and called for support from the West.

Many foreign anti-fascist fighters gave their lives to China during the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression (1937-45), the longest conflict of World War II. Among them was Canadian doctor Norman Bethune, a now legendary name in China, whom Lindsay took a picture of while he performed surgery on a wounded resistance soldier.

Going home

Two of Lindsay's three children with Li were born during their time in Yan'an - first Erica in 1942, then James in 1945, just months before the Japanese surrender.

After the war, the family moved to England, where upon his father's death the economics professor became the second Baron Lindsay of Birker, making Li a baroness and the country's first Chinese-born peeress.

After a stint teaching in Australia, Lindsay and his family settled in the US, where he died in 1994. He made only a few low-profile visits to China after the war, mostly in the role of an economist and scholar of international relations.

It is only recently that Lindsay - or Lin Maike, his Chinese name - has begun to gain attention on the Internet in China as an unsung hero, largely thanks to the touring photo exhibition now at Renmin University.

Today, more people are hailing him as a rare internationalist who helped the Chinese people through their most difficult time, and recorded their hardships and bravery.

Lindsay was a special figure in the Communist Party of China's history, for his "selfless and outstanding contribution" to the resistance, Zhang Baijia, former deputy director of the CPC Central Committee's Party History Research Center, said at a recent symposium on the sidelines of the exhibition.

"He was also wise to stay out of the complicated politics in this country (in the post-War years)," he added.

The photos on show in the exhibition, which Lindsay took mainly during his years at Jinchaji and Yan'an, offer "a fairly objective perspective" about World War II in China, according to Luo Cunkang, vice-curator of the Museum of the War of the People's Resistance against Japanese Aggression, in Beijing.

It was a national war led by the Kuomintang government of the time, but the CPC played an active and creative part, said An Ran, secretary-general of the China Foundation for Protection of Historical Relics.

Huang Xingtao, a history professor at Renmin University, agreed and added that the CPC succeeded in sustaining the resistance in occupied regions in north and northwestern China.

Commenting on the photos, professor Lu said they hold "precious value" because they carry the wartime memories that no Chinese can afford to forget.

Contact the writer at cuishoufeng@chinadaily.com.cn

Luo Wangshu contributed to this story.

(China Daily 04/08/2015 page6)

Today's Top News

Cause of China chemical plant blast identified

Fleeing war-torn Yemen, Chinese, foreign nationals share the same boat

Liu Xiang expected to announce retirement on Tuesday

Toilet revolution for tourism evolution: Opinion

Joint statement finalized at Iran nuclear talks

British PM joins in seven-party pre-election TV debate

China's ex-security chief Zhou Yongkang faces raft of charges

Death toll rises to 147 in Kenya university attack

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|