Train is on a journey of vision

Updated: 2011-11-10 07:51

By Wu Wencong (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

|

A nurse prepares a cataract patient for an operation on the Lifeline Express in Chuxiong, Yunnan province. Cui Meng / China Daily |

|

Chen Huijin, chief doctor on the Lifeline Express, explains cataract operations to patients and their relatives in the ward. Patients spend the night there after surgery. Photos by Cui Meng / China Daily |

|

Patients on the train are examined so doctors know what to expect before they begin cataract surgery. The train is spending three months at Chuxiong, Yunnan province. |

Eye hospital on tracks gives new hope to patients in remote areas, Wu Wencong reports from Yunnan province.

The train's whistle roused Chen Xi from her sleep as her bed vibrated to the rhythm of the tracks.

It was 2 am and again she had been woken by the shrill, even frightening, sound.

Chen drew the curtains, trying to keep the chill wind from sneaking into her tiny room. She knew it would be another long, cold night, the same as the previous night and the night before.

Chen was in a berth on a four-carriage train, actually a mobile eye hospital. It travels to remote areas in China and provides free cataract operations.

The train, Lifeline Express, stopped in Chuxiong Yi autonomous prefecture, Yunnan province, and Chen is one of the four medical professionals on board. She serves as ward head nurse.

The project started in 1997 from the Lifeline Express Hong Kong Foundation. Over the past 14 years, its four specially built trains have traveled to 90 poor areas in 27 provinces and autonomous regions on the Chinese mainland and helped more than 110,000 people see again.

Each Lifeline Express stays in one place treating patients for three months at a go, and is out in remote areas nine months every year, making three stops.

Chen, 30, was in the rural areas of Kashgar, Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region, with the train from July to September last year. She describes the area as "in extremely poor hygienic condition".

"I was bitten by fleas all over my body, and the bites wouldn't stop itching until I scratched the skin off. Once I even saw a flea on the apparatus I was using. My eyes were so close to it that it scared the hell out of me."

Though life on the train is tough, Chen applied to work again this year, in Southwest China, leaving her 4-year-old daughter at home for the second time. She values the charity of the project, the opportunity to train local nurses so they don't have to travel to Beijing for classes, and the chance to test her own management skills.

"I was a senior nurse back in Beijing, but here I am the head. There are five green hands and a bunch of odd jobs waiting for me to handle," she said.

Three of Chen's colleagues from Peking University Third Hospital are also on board, two doctors and one operating room head nurse. All are women close in age, and two have children who are not yet 2.

Three other, non-medical staff members are the head of the train, who works for the State Health Department and serves as director of the hospital; an attendant who takes care of all the mechanical problems; and a cook.

Each carriage has a separate function - a meeting room and a kitchen, lodging area, surgery, and ward. A large television and WiFi are provided. Facilities also include two bathrooms, two public restrooms and three washing machines, one dedicated to laundry from the ward.

Sleeping rooms are the same size as a typical train compartment for four, with only two beds, one used as a luggage rack. There are also a small desk and two lockers, each about a half-meter high, leaving little space for even one person.

"I'd say this situation is already a good one," said Wan Xiang, head of the train. "When we were in Zhengzhou, Henan province, last month, there were piles of rubbish outside and stray dogs everywhere."

Wan has been working on Lifeline Express since 2004. He spends about nine months on board every year, with support from his wife and 13-year-old son.

The 51-year-old said he is getting thinner year by year, but he seems as fit as a fiddle, with pride and contentment about his work that he doesn't bother to hide.

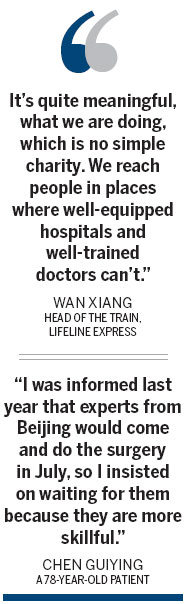

"It's quite meaningful, what we are doing, which is no simple charity," he said. "We reach people in places where well-equipped hospitals and well-trained doctors can't."

The preparation

Three days before the starting date for surgeries, two officials from the local disease control center arrived to collect samples of air and swab the table surfaces in the operating rooms to ensure there is no contamination.

Unlike a hospital in a building, the train hospital has no air-filtering equipment, which helps sterilize the room. Instead, formalin, a caustic formula that is disapproved by many hospitals, is used on the train to meet the same sterility standard.

The officials went into the operating rooms with gas masks on. When they came out, they complained about the sharp smell that made their eyes ache.

"How do your doctors do operations in the room, especially without a mask?" one of the officials asked Wan. The answer was a bitter smile.

"There is nothing we can do about this. Surely the formula will damage our health. I'll wait at least half a year before considering having a baby when I go back home," said Wang Xin, 27, the operating room head nurse, who got married this year.

Her workload was relatively light before the operations started, if the toxic fumes she inhales don't count. But Chen Xi worked more than 12 hours every day training local nurses, examining patients and getting all the information ready for the coming surgeries.

Chuxiong Yi autonomous prefecture has one city and nine counties. As all the patients are farmers, few of them speak Mandarin, which slows the progress of pre-operation checkups.

When Chen tried to imitate the local accent to tell her patient to close her eyes, everyone in the exam room burst into laughter.

They come with age

Cataracts are a common senile condition, like white hair, said Chen Huijin, 33, the chief doctor on the train. She said the cost of the surgery for one eye in Beijing is 5,000 to 6,000 yuan ($788 to $945).

Patients lose sight gradually as the lens in the eye becomes increasingly clouded, and those who are almost completely blind have priority for the free surgery. But Chen never expected the patients' conditions would be so severe.

Cataracts are divided into five stages. In Beijing, she said, a Stage 4 patient appears twice a year. But on the train, many patients are at Stage 5.

She said cataracts usually start to develop at age 60. Most people will undergo the surgery at about 70. But the day is longer and the sunshine stronger in Southwest China's Yunnan province, so most people develop cataracts early and their conditions worsen within a much shorter period.

"The later you do the surgery, the more difficult the operation will be and the more time required to recover," Chen Huijin said.

The youngest patient on the list is only 46.

In the operation, a doctor makes a 6-mm cut in the eye, removes the opaque lens and inserts an artificial replacement, an intraocular lens. Because resources are limited, each patient can have the surgery on only one eye when the train is in town.

During a pre-operation check, one patient insisted that her right eye be repaired, even though she had cataracts in both eyes, because she felt her right-eye vision was weaker. But it turned out she had a detached right retina, which could not be solved by cataract surgery.

"Such a case is common in many rural areas in China," said Hong Ying, 33, another doctor on board. "Due to their lack of medical knowledge, patients tend to blame loss of their vision on cataracts and will wait years for an operation.

"But it sometimes turns out to be another much more severe condition, like in this case. And the best chance for surgery has been missed."

Operations begin

The first day of surgery was a mess.

Some pre-op checks the local hospital was to have handled were not done. Apparatus sterilization didn't finish on time. The layout of equipment in the surgery room was unfamiliar, especially to the two doctors new to the train. Each room lacks one nurse to help, because the local hospital is running out of nurses to send over and the room is too small.

In Beijing, cataract surgery takes 15 minutes. But from 8 to 11 am on the train, only three surgeries were finished, in two rooms.

By 3:30 pm, the last patient had left the operating room. And Hong, who performed the last surgery and had missed lunch, decided to wait for dinner because she was needed in the ward at 5 pm. Before that, there was a meeting to attend.

Workload for the first week was planned at 15 patients each day. Head nurse Wang Xin said the pace would pick up after the first week. "But by then the workload will also be raised," to around 30. Her busiest day last year had 44 patients.

Chief doctor Chen Huijin underestimated the challenges of the surgery, even though such physical intensity is within her capacity.

"I had been warned about the obstacles such as the language and the fleas, but I never expected the situation of their eyes to be so severe that every step of the surgery has become an obstacle," she said.

Compared with the doctors' exhaustion, the patients were in fairly good moods as they rested in the ward after surgery.

Chen Guiying, 78, was the first patient that day, with surgery on her left eye. She couldn't help talking to others even though the nurses asked her to rest.

"I was informed last year that experts from Beijing would come and do the surgery in July, so I insisted on waiting for them because they are more skillful. And I'll wait until they come to Chuxiong again to do my other eye," she said.

Poverty is not the single reason that hinders the patients' undergoing cataract surgery.

Some said the waiting list is too long in the county hospital; others said they don't want to spend that much money, for off-train expenses, to cure their eyes if they cannot work in the fields again. Many of them are too old now for such hard labor.