|

|

|

| ||||||

|

|

| ||||||

|

|

| ||||||

|

|

|

|

Golden memories of a great man |

View:Grandeur and Centrality | ||

|

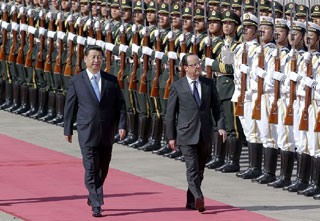

Momentous diplomatic breakthrough and what came next

With a long and narrow face, a high nose and imposing stature, Bernard de Gaulle is as easily recognizable as his last name. At the age of 91 he bears a strong resemblance to his uncle Charles de Gaulle, the late French president, whose decision to recognize Beijing's new government 50 years ago turned a new page in China-France relations and made De Gaulle a household name in China. One of the most memorable events of his career was his trip to Beijing in 1964 making him a pioneer of Sino-French commercial relations. "I never follow ideological confrontation," he says softly but firmly. "And I've always felt that China is important." In fact, the idea for the exhibition was first raised in 1953 when Bernard met Chinese officials of the China Council for the Promotion of International Trade in East Berlin. The decision was finalized in 1963, one year before the official normalization of diplomatic relations between Beijing and Paris, he says. Because of the exhibition, he managed to visit China in the 1960s and made the trip that his uncle had always wished to make but that never materialized. Bernard clearly recalls the difficulties of putting on the exhibition in China, a country that was completely unknown to him, but the exhibition was a success, and he was later invited to a lunch banquet and says he had a three-hour conversation with Chairman Mao Zedong in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province. "A lot of French people do not understand what China really is," he says. "It is the same for the Chinese as many heads of business corporations don't have much idea about France." Bernard's advice to current political leaders of China and France, in addition to improving mutual understanding, is patience. More than half a century later, Bernard still recalls the words his uncle wrote to him in a letter in 1954. "He wrote: 'Bernard, I follow your career in industry. You are in China. Despite the war, please continue and do not compromise yourself.'" Looking at the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Sino-French diplomatic relations, Bernard expresses optimism. "I am confident that our two countries will arrive at more successful relations in the coming years." [Full story] |

France and China, which are celebrating 50 years of diplomatic relations, have long had a clear view of their identities A statement is repeatedly attributed to Napoleon Bonaparte that he probably never uttered and that has become an inept cliche: "When China awakes, the world will shake." At a news conference on Sept 9, 1965, the French president Charles de Gaulle presented a more nuanced view: "A fact of considerable significance is at work and is reshaping the world: China's very deep transformation puts it in a position to have a leading global role." De Gaulle believed that a multipolar order would be more conducive to sustainable equilibrium than either unipolarity or the dangerous bipolar structure. In some circles, de Gaulle's politics of grandeur caused uneasiness or consternation. In entirely reducing de Gaulle's decision to politics one is missing a fundamental component of Gaullism. When he acknowledged China as a civilization, de Gaulle transcended the usual geopolitical calculations and took into account a more essential reality. For him the French administration had to work with another foreign government but, more fundamentally, he wanted the old French nation to connect with the immemorial Chinese civilization. De Gaulle thought and acted under the light of "la grandeur", a notion that is at the heart of France's national character. The imperatives of "liberte, egalite and fraternite", French propositions to the world, have been both a product and a generator of this passion for grandeur. Only the exalted aspiration of a nation in movement could proclaim such revolutionary principles, but they were at the same time the source of a powerful collective energy. In the Chinese context, centrality, zhong, mirrors French grandeur. If a sense of grandeur inspired the French monarchs, emperors and presidents, the Middle Kingdom envisioned for itself centrality under heaven. Versailles and the Forbidden City, Place de La Concorde and Tian'anmen Square are obvious architectural illustrations of the correspondence between the la Grande Nation and the Middle Kingdom. Animated by a conscious effort of rayonnement, or radiation, France aims to federate around what it conceives and enunciates as an enlightening project. By contrast, China's impact is by gravitation; the Middle Kingdom coheres around its demographic mass and the continuity of its civilization. Ironically, the gap between France's representation of itself and the weight of its power is widening and, contrasts with the Chinese centrality that is increasingly effective. Nevertheless, global evolution will not erase France's rich contribution to the making of Europe. More generally, it is precisely in the midst of the most challenging circumstances that the idea of grandeur itself can re-energize the country. The synergies between grandeur and centrality are more than the affirmation of two separate political identities; they are impulsions for the new humanism of a global renaissance, connections between East and West as much as North and South, and they are concrete universalism. [Full story] |

|

Related stories: |

|

Officials call for stronger partnership for Chinese, French firms |

||