Need for a well-managed slowdown

Updated: 2016-04-15 08:53

By Ed Zhang(China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||

While new data show China's capacity to handle a downturn, it's important to note salutary effects that spur future growth

A host of latest data (from trade to investment) show that the Chinese economy is stabilizing, contrary to the gloomy, if not sensational, conclusions of various distant observers at the beginning of the year.

In March, exports grew even with the domestic wage level much higher than just a few years ago.

Domestic electricity use climbed, indicating greater business activity.

Most importantly, perhaps, a moderate rise in inflation would provide the much-needed incentive for consumers to buy more, and for companies to produce more.

There can be no one, in the right state of mind, who could go on talking about the economy's imminent collapse.

Investors can be assured that, this year, the China market will feature less uncertainty and appear less dangerous than in 2015.

Of course, the slowdown continues, and will continue, as it would in any country after its economic takeoff. In the long run, one has every reason to expect China's GDP growth rate to come down further.

But the very fact that a government can somehow manage the speed and severity of a large economy's slowdown should be seen as a good thing by its investors and trade partners. That means China has some ability to at least avoid too steep a decline, or a free-fall-type recession.

Compared with the managed "recovery" immediately after the outbreak of the 2008 global crisis, a recovery boosted entirely by the government's hasty prescription of a super dose of "financial steroids" (4 trillion yuan, or more than $600 billion, worth of easy credit), the managed slowdown is a much more important kind of achievement, reflecting a higher level of leadership skill than simply foolhardy spending of bailout funds.

A managed slowdown can help government economic officials learn a lot of things about the country before they choose the most suitable policies, such as how bad things may be in the most difficult provinces, and how strong business resilience may be in provinces that turn out the best growth records.

Such differences cannot be easily spotted in a time of fast growth or a slump across the board. It was why the urgency in reforming state-owned enterprises was never so acutely felt, despite the central government's repeated call for discarding the economy's unsustainable development model.

It was also why, despite the central government's pledge more than a decade ago to revitalize the country's rust belt in the northeastern provinces, a bastion of old heavy industries, local governments have never made a serious effort to help the growth of local businesses, especially those owned by private proprietors.

It is only in the process of a managed slowdown on the national level that people can learn, from the emerging differentiation among regions and industries, where the best cities are in terms of their business environment, where the most competitive industries are, and where future is being made.

It is only now that more people have come to realize that many companies continuing to survive in the time of easy credit are by nature "zombie" enterprises no longer able to exist when faced with real competition. They don't deserve any more bailout funds. The government has better use for the money, like helping their workers find other jobs.

Having said this, it is clear that China's challenge now is to try to sustain its managed slowdown - for as long as is needed - to perform euthanasia (and there could be different ways of doing so) on its zombie enterprises while building the economic freedom needed by a new generation of competitive enterprises.

To yield the expected results, such a process may take five years or even longer in the most difficult northeastern provinces.

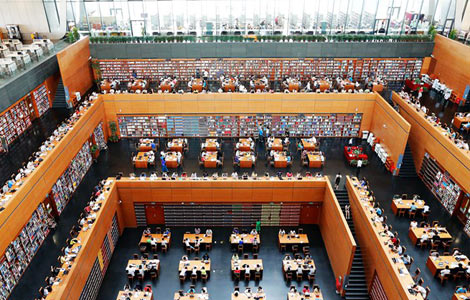

In the more-advanced regions, thousands of new companies have been established as a result of the government's move to curtail its administrative powers in the last couple of years, while SOEs make up only a very small portion of the local economy.

Their economic transition may come along more easily - so long as the local governments in those regions can keep control of their overall debt level and avoid making policy flip-flops too often.

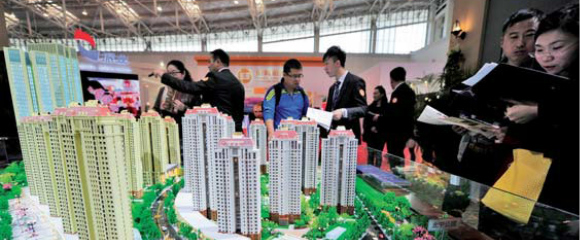

With more economic freedom, a continuing process of government-led investment in public projects, and a relatively stable housing market, most of the country's city clusters can generate enough GDP growth by the end of the year.

The author is editor-at-large of China Daily. Contact the writer at edzhang@chinadaily.com.cn

Today's Top News

Inspectors to cover all of military

Britons embrace 'Super Thursday' elections

Campaign spreads Chinese cooking in the UK

Trump to aim all guns at Hillary Clinton

Labour set to take London after bitter campaign

Labour candidate favourite for London mayor

Fossil footprints bring dinosaurs to life

Buffett optimistic on China's economic transition

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|