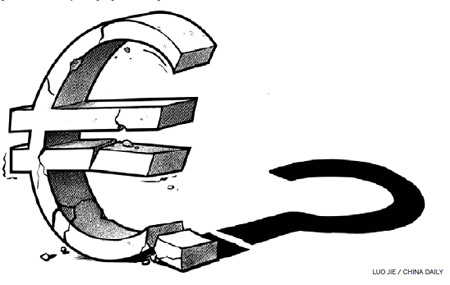

Debate: Euro

Updated: 2011-12-12 08:00

(China Daily)

|

|||||||||

What ails the euro and the European Union? Two professors, one from Harvard, the other from Princeton, share their views on the crisis.

Martin Feldstein

Europe is not the United States

Europe is now struggling with the inevitable consequences of imposing a single currency on a very heterogeneous collection of countries. The budget crisis in Greece and the risk of insolvency in Italy and Spain are just part of the problem caused by the single currency. The fragility of the major European banks, high unemployment rates and the large intra-European trade imbalance (Germany's $200 billion current-account surplus versus the combined $300 billion current-account deficit in the rest of the eurozone) also reflect the use of the euro.

European politicians who insisted on introducing the euro in 1999 ignored the warnings of economists who predicted that a single currency for all of Europe would create serious problems. The euro's advocates were focused on the goal of European political integration, and saw the single currency as part of the process of creating a sense of political community in Europe. They rallied popular support with the slogan "One Market, One Money", arguing that the free-trade area created by the European Union would succeed only with a single currency.

Neither history nor economic logic supported that view. Indeed, EU trade functions well, despite the fact that only 17 of the EU's 27 members use the euro.

But the key argument made by European officials and other defenders of the euro has been that, because a single currency works well in the United States, it should also work well in Europe. After all, both are large, continental, and diverse economies. But the argument overlooks three important differences between the US and Europe.

First, the US is effectively a single labor market, with workers moving from areas of high and rising unemployment to places where jobs are more plentiful. In Europe, national labor markets are effectively separated by barriers of language, culture, religion, union membership and social-insurance systems.

To be sure, some workers in Europe do migrate. In the absence of the high degree of mobility seen in the US, however, overall unemployment can be lowered only if high-unemployment countries can ease monetary policy, an option precluded by the single currency.

A second important difference is that the US has a centralized fiscal system. Individuals and businesses pay the majority of their taxes to the federal government in Washington, rather than to their state (or local) authorities.

When a US state's economic activity slows relative to the rest of the country, the taxes that its individuals and businesses pay to the federal government decline, and the funds that it receives from the federal government (for unemployment benefits and other transfer programs) increase. Roughly speaking, each dollar of GDP decline in a state like Massachusetts or Ohio triggers changes in taxes and transfers that offset about 40 cents of that drop, providing a substantial fiscal stimulus.

There is no comparable offset in Europe, where taxes are almost exclusively paid to, and transfers received from, national governments. The EU's Maastricht Treaty specifically reserves this tax-and-transfer authority to the member states, a reflection of Europeans' unwillingness to transfer funds to other countries' people in the way that Americans are willing to do among people in different states.

The third important difference is that all US states are required by their constitutions to balance their annual operating budgets. While "rainy day" funds that accumulate in boom years are used to deal with temporary revenue shortfalls, the states' "general obligation" borrowing is limited to capital projects like roads and schools. Even a state like California, seen by many as a poster child for fiscal profligacy, now has an annual budget deficit of just 1 percent of its GDP and a general obligation debt of just 4 percent of GDP.

These limits on state-level budget deficits are a logical implication of the fact that US states cannot create money to fill fiscal gaps. These constitutional rules prevent the kind of deficit and debt problems that have beset the eurozone, where capital markets ignored individual countries' lack of monetary independence.

None of these features of the US economy would develop in Europe even if the eurozone evolved into a more explicitly political union. Although the form of political union advocated by Germany and others remains vague, it would not involve centralized revenue collection, as in the US, because that would place a greater burden on German taxpayers to finance government programs in other countries. Nor would political union enhance labor mobility within the eurozone, overcome the problems caused by imposing a common monetary policy on countries with different cyclical conditions, or improve the trade performance of countries that cannot devalue their exchange rates to regain competitiveness.

The most likely effect of strengthening political union in the eurozone would be to give Germany the power to control the other members' budgets and prescribe changes in their taxes and spending. This formal transfer of sovereignty would only increase the tensions and conflicts that already exist between Germany and other EU countries.

The author is a professor of Economics at Harvard University, US.

Project Syndicate

Harold James

Stable money foundation of order

The purpose of creating a common currency has been largely and surprisingly forgotten in crisis-torn Europe. Instead, there seem to be more pressing concerns: gloomy speculation about the eurozone's impending collapse and desperate attempts to find institutional fixes to its extensive governance problems.

But the euro was not just the outcome of an idiosyncratic quest to reduce the wear on pockets stuffed with odd national coins, or to facilitate intra-European trade. The bold European experiment reflected a new attitude about what money should do, as well as how it should be managed. In opting for a "pure" form of money, created by a central bank independent of national authority, Europeans self-consciously flew in the face of what had become the dominant monetary tradition.

In the 20th century, the creation of money - paper money - was usually thought to be the domain of the state. Money could be issued because governments had the power to define the unit of account in which taxes should be paid. This tradition went back well before paper, or fiat, currencies. For many centuries, even while metallic money circulated, the task of defining units of account - livres tournois, marks, gulden, florins or dollars - remained a task of the state (or of those with political power).

Abuse of this role, with governments addressing excessive debt by inflating it away, was deeply destructive of political order in the first half of the 20th century. After World War II, the liberal politicians most committed to European federalism saw this point clearly. The economist, central-bank governor, finance minister and president of the Italian Republic, Luigi Einaudi, pleaded the case in the immediate aftermath of the war: "If the European federation takes away from the individual states the power of running public works through the printing press, and limits them to expenses that are financed solely by taxes and voluntary loans, it will by that act alone have accomplished a great work."

But monetary abuse is no less dangerous in political systems with multi-layered authority, and in the past often led to the breakup of federal states. That is because inflation is not a benign cure for economic ills, in which beneficent and stimulatory effects are spread equally over the entire region under the inflationary monetary authority. Making inflation depends on the central bank's decision to monetize specific debt instruments.

After all, the monetary authority never decides simply to convert every obligation into money. Instead, it decides that some industries, banks or political authorities need to be sustained for the general good. Those industries, banks, and political authorities that are not so privileged are inevitably resentful, and view the central bank's actions as an abuse of power. In federal systems, in particular, the businesses and political authorities far removed from the center are most likely to be excluded from the monetary stimulus and hence are inclined to be resentful.

Hyperinflation in Germany in the 1920s fanned separatism in Bavaria, the Rhineland, and Saxony, because these remote areas thought that Germany's central bank and central government in Berlin were discriminating against them. The separatists were politically radical - on the left in Saxony, and on the far right in Bavaria and the Rhineland.

There are also more recent cases of the same effect. In late-1980s Yugoslavia, the monetary authorities in Belgrade were inevitably closest to Serbian politicians such as Slobodan Milosevic and to Serbian business interests. As a result, the Croats and Slovenes wanted to be out of the federation. In the erstwhile Soviet Union, inflation appeared as an instrument of Moscow bureaucrats, and there, too, more remote areas sought to break away.

The makers of modern Europe saw that unstable and politically abused money would be a European nightmare, and lead to destructive national animosities and antagonisms. They were supported by the 20th century's two most influential economists, Friedrich von Hayek and John Maynard Keynes.

Hayek was the most consistent critic of state-produced money. His proposal, competitive currencies produced by "free banking" in which numerous private authorities would issue their own money, was more radical than the solution adopted by Europeans in the 1990's. But the Hayekian element of a money-issuing authority that was extensively protected against political pressures, and consequently against political opprobrium, was a key part of the European Union's Maastricht Treaty. Keynes, too, in planning for the post-World War II order, proposed a synthetic global currency that would guarantee stability and prevent deflation.

The vision of central-bank independence as a necessary part of the constitution of a sound and stable political order was not simply a European construct in the 1990s. It was also reflected in legislative changes affecting other central banks, and in central bankers' growing prestige.

That view is now seriously challenged. In the aftermath of the worst financial crisis since WWII, central banks are once again being called on to monetize securities issued by some debtors, but not others. That task of selecting between debtors is highly political, and poisons the idea of monetary stability.

Jean-Claude Trichet, until recently the president of the European Central Bank, liked to claim that money was like poetry, before adding that both give a sense of stability. That unusual but accurate formulation is reminiscent of General August Neidhardt von Gneisenau's famous reply to the Prussian king, who dismissed as "nothing more than poetry" von Gneisenau's patriotic concerns in the early 19th century. "Religion, prayer, love of one's ruler, love of the fatherland, what are these but poetry?" von Gneisenau asked. "Upon poetry is founded the security of the throne."

Stable money, too, is the foundation of political order. We should not allow ourselves to be so overwhelmed by today's crisis that we forget that.

The author is professor of history and international affairs at Princeton University and professor of history at the European University Institute, Florence.

Project Syndicate

(China Daily 12/12/2011 page9)