Op-Ed Contributors

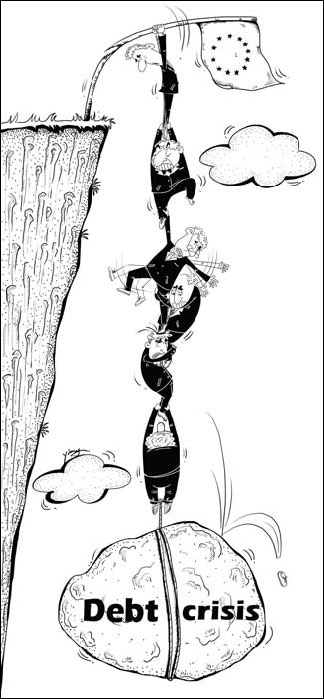

Debate: Eurobonds

Updated: 2011-09-19 08:04

(China Daily)

|

Wang Xiaoying / China Daily |

Are eurobonds the panacea for all the European Union's ills? 'No', says a professor of economics in Berlin, while a Harvard professor says it could.

Klaus F. Zimmermann

Better not depend on false promise

It seems like 1997 all over again. The big difference is that, this time, it's Europe, along with the United States, but definitely not Asia, that is teetering.

At a time when the entire financial world looks at developments in Europe with baited breath, it is pivotal that we Europeans resist the temptation to put the cart before the horse yet again - and jump headlong into new economic realities largely based on either wishful or overly optimistic thinking.

That, after all, is precisely what we did in the run-up to the euro, when all of official Europe put its collective hopes into the promising-sounding "Growth and Stability Pact". At the time, the switch to a common European currency was sold, in part, with the argument to put an end to American dominance of foreign exchange markets in general - and to the dollar's status as the reserve currency in particular.

This time, the case for launching eurobonds is made along similarly tantalizing lines in the global power game. The creation of eurobonds is intended to have European debt capital markets compete head on with the US Treasury market. By making European markets equally deep and liquid, the hope is for lower interest rates on that debt.

Such grand designs aside, in a debt-infested world, all that ultimately matters is fiscal stability. That is why, in my view, before we get too excited and see eurobonds as some kind of panacea, we would do well to acknowledge that we have already failed in the mission of obtaining fiscal stability once. We cannot afford to do so again.

That certainly is the unequivocal view of the financial markets. There are two other, equally powerful reasons speaking in favor for consolidating our finances: first, fiscal stability is needed to have any hope of bringing about sustainable economic growth, and second, it is needed to stop burdening future generations with ever more debt.

Eurobonds can be a useful instrument over the longer term, as the end point of a process of fiscal consolidation, once the hard labor required in that regard has been done. In other words, their introduction should be a reward for past performance, not an illusory incentive for better fiscal behavior in the future. The latter approach is precisely what we embraced at the launch of the euro, with known results (that is, near failure).

Europe's credit hinges on the fiscal performance of countries such as Germany, the Netherlands, Denmark, Finland and Poland. Making these countries, in effect, fiscally liable for the debt of other nations, as the premature introduction of eurobonds would do, is a recipe for the euro's demise.

Moreover, notions such as a "fiscal union" are not to be taken lightly. Even those who argue that it is in the logic of the European integration project to move in that direction - and who say that the process of the formation of the United States of America historically shows the way forward for Europe - forget one crucial thing. Most US states have a balanced budget requirement to meet each and every year. In addition, in the US there is no federal bailout clause for the debts incurred by individual states.

What is needed then is not some heady optimism, but sober thinking and a disciplined sequencing of events and conditions before we can introduce eurobonds. Key among them is the so-called debt brake, a constitutional requirement in Germany as of 2016 that will severely limit further increases in public debt in narrowly defined emergency situations. In a positive sign of rising budgetary seriousness throughout Europe, this self-disciplining instrument is now being introduced, or contemplated, in Spain and Italy, too. In many ways, this tool is akin to the balanced budget requirements at the US state level.

This also points the way to what is needed in case eurobonds are being introduced. Profound changes in the institutional setup will be required. In addition to the introduction of a European finance minister, there is, most notably, a requirement for a eurozone body with unassailable veto rights over national budgets (in cases of continued fiscal malfeasance) - with all that entails for rethinking the traditional prerogatives of national parliaments in terms of their historic power of the purse.

But for Europe, the lesson of the past 15 years is clear. National governments cannot, on one hand, merrily issue debt - and then, on the other hand, expect other European nations to stand in for that debt in the end. National sovereignty cuts two ways. It is there when you manage your affairs competently and with discipline - and it must be restricted when you are incapable, or unwilling, to raise sufficient revenues domestically. Obliging others with no restraint is a recipe for disaster.

Finally, it is important to realize for all those constantly chanting the "spend, baby, spend" refrain that the stability-oriented German position is, surprisingly perhaps, very Keynesian in nature. The eminent British economist was far from the one-armed economic policy operative he is made out to be today.

Yes, Keynes explicitly advocated high government spending in times of economic (near-)collapse, but only under the simultaneous and unbending condition that, in sunnier times, savings would be piled up to pay back past debts - and, ideally, to build up a rainy day fund.

In that sense, the German constitutional provision requiring strict limits on further debt increases is, in effect, giving the tough side of Keynes's policy prescriptions the rank of constitutional law. In a debt-addicted world, that is an important policy innovation.

The author is director of the Institute for the Study of Labor, and professor of economics at the University of Bonn, Germany.

Dani Rodrik

It's a crisis of fiscal imagination

Greedy banks, bad economic ideas, incompetent politicians: there is no shortage of culprits for the economic crisis in which rich countries are engulfed. But there is also something more fundamental at play, a flaw that lies deeper than the responsibility of individual decision-makers. Democracies are notoriously bad at producing credible bargains that require political commitments over the medium term. In the United States and Europe both, the costs of this constraint on policy has amplified the crisis - and obscured the way out.

Consider the US, where politicians are debating how to prevent a double-dip recession, reactivate the economy and bring down an unemployment rate that seems stuck above 9 percent. Everyone agrees that the country's public debt is too high and needs to be reduced over the longer term.

While there is no quick fix to these problems, the fiscal-policy imperative is clear. The US economy needs a second round of fiscal stimulus in the short term to make up for low private demand, together with a credible long-term fiscal-consolidation program.

As sensible as this two-pronged approach - spend now, cut later - may be, it is made virtually impossible by the absence of any mechanism whereby US President Barack Obama can credibly commit himself or future administrations to fiscal tightening. So any mention of a new stimulus package becomes an open invitation to those on the right to pounce on a Democratic administration for its apparent fiscal irresponsibility. The result would be a fiscal policy that would aggravate rather than ameliorate America's economic malaise.

The problem is even more extreme in Europe. In a futile attempt to gain financial markets' confidence, country after country has been forced to follow counter-productive austerity policies as the price of support from the International Monetary Fund and the European Central Bank. Yet requiring deep fiscal cuts, privatization and other structural reforms of the type that Greece has had to undertake risks greater unemployment and deeper recessions. One reason that interest-rate spreads in financial markets remain high is that distressed eurozone countries' growth prospects look weak.

Here, too, it is not difficult to discern the broad outlines of a solution. Stronger countries in the eurozone must allow these spreads to narrow by guaranteeing the new debts of countries from Greece to Italy, through the issuance of eurobonds, for example. In return, the highly indebted countries must commit to multi-year programs to restructure fiscal institutions and enhance competitiveness - reforms that can be implemented and will bear fruit only over the medium term.

But, once again, this requires a credible commitment to an exchange that requires a promise of action later in return for something now. German politicians and their electorates can be excused for doubting whether future Greek, Irish or Portuguese governments can be counted upon to deliver on current leaders' commitments. Hence, the impasse with the eurozone is becoming mired in a vicious circle of high debt and economic austerity.

Democracies often deal with the problem of extracting commitments from future politicians by delegating decision-making to quasi-independent bodies managed by officials who are insulated from day-to-day politics. Independent central banks are the archetypal example. By placing monetary policy in the hands of central bankers who cannot be told what to do, politicians effectively tie their own hands (and get lower inflation as a result).

Unfortunately, American and European politicians have failed to show such imagination when it comes to fiscal policy. By implementing new mechanisms to render the future path of fiscal balances and public debt more predictable, they could have averted the worst of the crisis.

Compared to monetary policy, fiscal policy is infinitely more complex, involving many more trade-offs among competing interests. So an independent fiscal authority modeled along the lines of an independent central bank is neither feasible nor desirable. But certain fiscal decisions, and most critically the level of the fiscal deficit, can be delegated to an independent board.

Such a board would fix the maximum difference between public spending and revenue in light of the economic cycle and debt levels, while leaving the overall size of the public sector, its composition and tax rates to be resolved through political debate. Establishing such a board in the US would do much to restore sanity to the country's fiscal-policymaking.

Europe, for its part, requires a determined step toward fiscal unification if the eurozone is to survive. Removing national governments' ability to run large deficits and borrow at will is the necessary counterpart to a joint guarantee of sovereign debts and easy borrowing terms today.

Yet this cannot mean that fiscal policy for, say, Greece or Italy would be run from Germany. A common fiscal policy implies that the elected leaders of Greece and Italy would have some say over German fiscal policies, too. While the need for fiscal unification is increasingly recognized, it is not clear whether European leaders are willing to confront its ultimate political logic head-on. If Germans are unable to stomach the idea of sharing a political community with Greeks, they might as well accept that economic union is as good as dead.

Politics, it is said, is the art of the possible. But possibilities are shaped by our decisions as much as they are by our circumstances. As matters currently stand, when future generations place our leaders in historical perspective, they are most likely to reproach them, above all, for their lack of institutional imagination.

The author is a professor of international political economy at Harvard University and author of The Globalization Paradox: Democracy and the Future of the World Economy. Project Syndicate

(China Daily 09/19/2011 page9)

E-paper

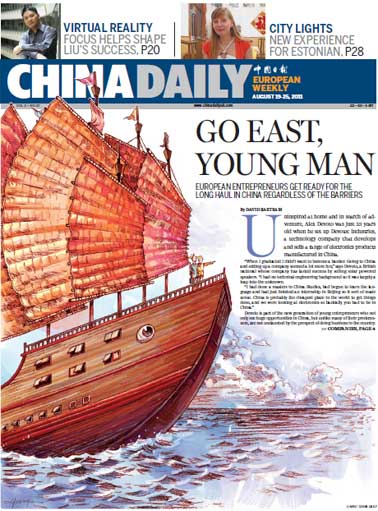

The snuff of dreams

Chinese collectors have discovered the value of beautiful bottles

Perils in relying on building boom

Fast forward to digital age

Bonds that tie China. UK

Specials

Let them eat cake

Cambridge University graduate develops thriving business selling cupcakes

A case is laid to rest

In 1937, a young woman'S body was found in beijing. paul french went searching for her killer

Banking on change

Leading economist says china must transform its growth model soon