Medicine for the mind

Updated: 2013-10-16 07:07

By Wang Jiaquan, Lan Xi and Tan Haoxuan (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

A program teaching mental-health patients painting, dance, music and crafts is having remarkable results. Xinhua writers Wang Jiaquan, Lan Xi and Tan Haoxuan report.

Wang Yu seems to be proud of her peony paintings, but there's no hint of pride on her face when she asks her visitors for comments.

She remains expressionless as the visitors wow at a scroll of the large, showy pink blossoms she has painted.

The blossoms were painted more than a year ago, and her new subject of choice is chrysanthemums, which she calls mums, for short.

However, Wang continues with the query "Are my peonies beautiful?" but she is staring at a piece of paper covered in sketches of yellow chrysanthemums.

"Yes, they are beautiful, but we have to finish our mums' petals and leaves today. All right?" her teacher Jia Lixian says, hoping to divert her student's attention toward the flowers they are painting.

Wang begins to copy Jia as the teacher shows her how to control the brush strokes.

The 30-something woman is among a group of unusual students of traditional Chinese painting, who are learning the skill as part of a rehabilitation therapy at a Beijing hospital for mental disorder sufferers.

The program established at Beijing's Ping'an Hospital in 2011 is maintained by a local group of senior citizens who offer training in painting, dance, music and handicraft.

Jia, 63, teaches painting, a skill she learned at a community college for senior citizens, while her husband Tian Guohua serves as head of the volunteer group.

Jia and Tian decided to create the program after their mentally ill son died three years ago. After experiencing the difficulty of raising a son with a mental disorder, they decided to create the program to help other patients and their families.

Their idea was welcomed by the hospital, which has more than 140 patients with mental disorders.

Hospital manger Li Shuo says social participation is necessary to ensure the success of the patients' recovery, especially for the restoration of their social skills, such as interpersonal communication.

However, not everybody is fit to work with such patients, Li says. The hospital's management decided to permit Tian's group to volunteer because they believed the group's diverse skill set would aid in the recovery process.

Tian's volunteer group is composed of more than 30 members, most of whom are over the age of 60.

When the program began, some of the doctors and nurses refused to believe that their patients would one day become capable of painting anything, let alone peonies, a subject that requires delicate use of brush and change of color.

Jia managed to teach her students the skill, although it was not an easy process.

"You need a lot of patience when you teach them how to paint. They are prone to forget things and sometimes their hands are not agile enough to command complicated curves as a side effect of drug therapy," Jia says.

"But you cannot get frustrated or angry with them. Your only choice is to help them start from the very beginning if they forget what they have previously learned."

You Guifang, who teaches dance, has had similar problems. Dance requires nimble movements, but some patients cannot respond to the rhythms accurately. The 67-year-old You sometimes has to bend down to help move their feet with her hands.

However, Jia and You are aware that they are not making artists or dancers.

"We are interacting with them to make them feel happy and help them learn to communicate with others," Jia says.

For Bao Fulan, participating in the voluntary program requires not only a good heart and patience, but also courage.

When Tian invited the 72-year-old woman to teach handicrafts at the hospital, her family members and friends warned her that the patients might be unpredictable or dangerous.

She admits that she was initially scared about the prospect of spending time with the patients, but agreed to give it a shot, finding the experience was nothing like what her relatives warned her about.

"Before I came here, I thought the patients were madmen, as I was told when I was a child. But I have found that they are very polite and gentle, much like children, and need care from others," Bao says.

The hospital uses strict measures and the volunteers receive training when they start working with the program to ensure the safety of everyone involved.

Bao and her volunteers keep a close eye on the scissors and tweezers that are frequently used in the handicraft that she teaches. Three doctors and nurses are also on hand when the courses are taught.

Bao's initial worries were not unfounded. Violent attacks carried out by people with mental disorders happen every year. Last month, a mentally ill man attacked bystanders with a knife at a Beijing supermarket, killing one person and injuring three others.

These incidents have exposed loopholes in the medical care system, with many mentally ill people slipping through the cracks. Reports on the incidents have also served to widen the gap between the general public and the mentally ill, who are often the target of discrimination in the country.

According to statistics from the National Health and Family Planning Commission, China has more than 16 million people with serious mental disorders.

The country's first Mental Health Law, which took effect on May 1, is intended to boost public participation in caring for the mentally ill by calling for local governments to support and encourage individuals and organizations that wish to provide services for such patients.

The law has been good news for mental hospitals and patients, but it will take time for society to rid itself of discrimination, hospital manager Li says.

"Drug therapy is a basic but very small part of the recovery process. Receiving care from relatives and community members can reshape patients' perceptions of society, and thus is helpful for them to return to normal life," Li says.

In this sense, Li says, the volunteers have helped change the hospital's environment and are playing an important role that drugs cannot fill. "When the patients see people among them in the hospital who aren't in white gowns, they feel differently."

Doctors and nurses have found that patients who have participated in the volunteer therapy program have shown less hostility to the people around them, including hospital staff and relatives, Li says.

Some of the more movement-oriented therapy sessions have also helped improve patients' use of their limbs, which are often affected by the long-term use of drugs.

Li says the volunteers are setting a good example for the public in terms of the attitudes they have displayed toward the patients.

"The patients have self-awareness, self-esteem and emotions just like you and me. They need the embrace of their families and society," Li says.

Wang Yu, the traditional Chinese painting student, may serve as an illustration to Li's comments.

When asked why she likes painting, the woman says that Jia is a good teacher. "She would come to teach us even when she has a fever."

|

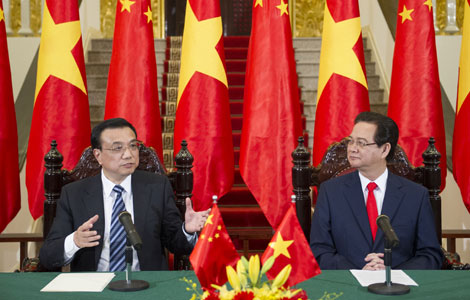

Jia Lixian teaches a patient traditional Chinese painting as part of a rehabilitation therapy at a Beijing hospital for mental disorder sufferers. Wang Jiaquan / for China Daily |

(China Daily 10/16/2013 page20)

Today's Top News

London to develop further as yuan trading hub

Death toll of Philippine earthquake rises to 99

Overseas M&A deals reach record high in 1st half

ODI set to become more diverse

Renewed move to streamline bloated sectors

Most EU urbanites breathe in pollution

Cooking fumes debated as cause of pollution

Agreements with UK to boost wider use of yuan

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|