Justice, Tibet style

Updated: 2013-06-27 06:48

By Tang Yue and Wang Huazhong (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

Dawagyizom, right, a Lhasa native and lawyer who has worked at the Legal Assistance Center of the Tibet autonomous region for five years, talks with her client Lhadron. Photos by Daqiong / China Daily |

|

Zhou Yun, left, meets Chen Bo, deputy director of the center. Chen helped Zhou win compensation of 230,000 yuan after he lost a kidney in a work-related accident. |

Autonomous region develops unique ways to administer the law, Tang Yue and Wang Huazhong report in Lhasa.

When someone is killed in a traffic accident in China the guilty party usually has to compensate the victim's family, and might even serve a prison term.

But that's not always the case if the accident happens in the Tibet autonomous region.

"Because of their Buddhist beliefs, people in Tibet think there's no need to increase a family's pain when someone's life has already gone. They believe that doing good to others will help their lost loved one to reincarnate," said Dawagyizom, a Lhasa native and lawyer who has worked at the Legal Assistance Center of the Tibet autonomous region for five years.

"That's why you see a lot of fatal traffic accidents resolved more easily here than in other parts of the country."

Compared with people in the more affluent areas of China, many residents of Tibet lack legal awareness, despite the huge progress made in recent decades, said Dawagyizom.

"In Lhasa, it's fine but in a lot of other regions, especially the rural areas, people may resort to other means, rather than seeking a legal solution."

To better help people defend their rights through the process of law, especially those from poverty-stricken areas, the legal assistance center was established in Lhasa in 2001. It now employs more than 120 employees and covers every one of Tibet's 73 counties.

The center not only helps people defend their rights, but has also helped to change traditional views.

One of Dawagyizom's clients is Lhadron, a 34-year-old Lhasa housewife. Her father Palden Tsering fought with Lhadron's stepmother last year, inflicting a slight injury to her leg in the process.

Although the wound was minor, Lhadron's stepmother went to the hospital to have it checked. While at the hospital, the woman became enraged, grabbed a knife and accidentally severed an artery in her leg. She later died of the injury.

"I don't know much about the law. At first, I thought my father would be tried and given a death sentence because my stepmother died. I cried everyday," said Lhadron.

Relatives advised her to seek help from the assistance center. She was seen by Dawagyizom, who collected evidence from witnesses at the hospital that proved the fatal injury was inflicted accidentally and was not a result of the fight between husband and wife.

In addition to consulting a lawyer, Lhadron also spent a long time praying in the hall the family uses for worshipping Buddha.

"I believe Buddha must have helped my father through this troubled time," said Lhadron, after offering incense to a statue of the Buddha.

"But what's different now is that I don't only believe in the blessings of Buddha, but also in the power of the law. In the past, we thought it shameful to go to court."

Labor disputes

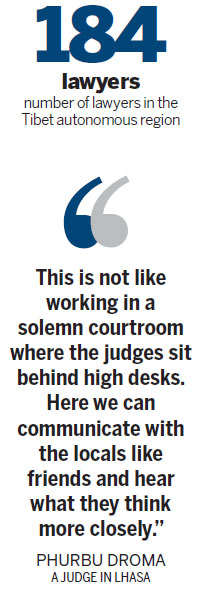

According to Chen Bo, deputy director of the center, 70 percent of the cases it deals with are labor disputes.

"There are similar cases all over China - mainly construction workers who haven't been paid for work they've done. Some are from outside Tibet, while others are local farmers or herdsman," said Chen, 45.

As a Han Chinese, Chen believes the Tibetan he acquired during childhood has helped him win the trust of the local people.

"But I don't really care if the people who ask our advice are Han or Tibetan. All people are equal before the law. As a lawyer, my responsibility is simply to defend the rights of every individual."

Zhou Yun has benefited from the center's work. The 37-year-old moved to Lhasa from neighboring Sichuan province on March 19, earning 210 yuan ($34) a day installing equipment in a cement plant.

He lost a kidney in a work-related accident on April 5. Although his boss agreed to pay the surgical fee of 35,000 yuan, he was reluctant to discuss compensation.

Zhou's wife, Gong Yongying, said at the center on May 9: "When I saw all the tubes in my husband's body, I was really terrified and didn't dare think of the future."

Zhou said, "I have no savings to hire a lawyer, but thanks to lawyer Chen's help, I can hold on and fight for what I deserve." He eventually received compensation of 230,000 yuan.

Mobile courts

Sometimes, it's not just the cost that prevents people from consulting a lawyer, often they are daunted by distance.

Fewer than 3 million people live in Tibet's 1.2 million square kilometers of area. Settlements are few and far between, meaning that for many people the nearest judicial center may be hundreds of kilometers away.

The problem was resolved by the use of "mobile courts" that traveled across the vast plateau dispensing justice.

In the early years, the court officials traveled on horseback, but in 2009, cars were introduced for 73 lower-level courts to speed up and simplify the process.

"We help them to access the most convenient judicial services in the shortest period of time and at the lowest cost," said Phurbu Droma, who has worked as a judge at the mobile court of Doilungdeqen county in Lhasa for four years.

On a sunny day in April, the 29-year-old drove for two hours to Nanba village to erect a tent at the foot of the snowcapped mountains.

She and her colleagues were there to try a case in which an employer was accused of delaying payment of a worker's salary for half a year.

Tondub Tsering, the plaintiff, said that when village government officials tried, but failed, to persuade his employer to pay up, he decided to call the mobile court.

"The judges came and opened the trial. The verdict of the court is highly prestigious and must be adhered to."

According to a work report compiled by the autonomous region's high people's court, the mobile courts have traveled 3.62 million km and tried 17,800 cases in the four years since they were introduced.

"This is not like working in a solemn courtroom where the judges sit behind high desks. Here we can communicate with the locals like friends and hear what they think more closely," said Phurbu Droma.

The mobile courts have also helped to raise locals' awareness of the law, even when a trial is not required. Locals can call on 46 liaison officers in 34 villages in Doilungdeqen county when they need to consult them or file a lawsuit.

Gesang Drolkar, 48, a local official, said people used to turn to seniors and the Living Buddha to resolve conflicts in the past.

But the seniors' judgments were sometimes biased and favored one side, especially if the cases involved their relatives or friends. "The practice was not conducted according to the law and was often unfair."

As a result, local traditions have changed. For example, it has long been the practice that if a couple divorced the father would be awarded custody of the male children, while the mother got the girls. That practice has now been phased out.

However, Phurbu Droma said the region faces a shortage of qualified judges, but the number of cases is rising. Moreover, because the mobile courts reduce and remit most of the costs of litigation, the courts face economic difficulties.

"Traveling on the plateau is not easy. We came here so that the villagers would not have to take the trouble of traveling repeatedly to the county seat where the court is based," she said.

Contact the writers at tangyue@chinadaily.com.cn and wanghuazhong@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily 06/27/2013 page6)

Today's Top News

US Senate approves landmark immigration bill

Park's visit aids 'trust-building process'

Industry enjoys profitable month

EU budget deal sealed

IPOs likely to resume in H2

'No more illegal tax cuts for investors'

Shenzhen, Belgium to boost ties

Hiring index signals further job weakness

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|