Too many tastes?

Updated: 2012-11-18 07:58

(The New York Times)

|

|||||||||||

|

From Atera's menu, top from left: Rose in wildflower sherbet; scallop, sake lees and frozen sour apple; roast duck with dried flowers and rose hips; beet ember with smoked trout roe. Middle row: dried tomato with raw-milk ice cream; noodles in roasted chicken bouillon; vanilla birch cotton candy and sweet fern; aerated pumpkin bread with brown butter sediment and whipped cream. Bottom row: beef with matsutake and sunchoke; lamb tartare; bourbon cask ice cream sandwich; pastrami of duck hearts, market vegetables and herbs. Photographs by Karsten Moran for The New York Times |

Multi-course menus might be too much of a good thing

In the hands of a chef who grasps the challenges and possibilities, a tasting menu can yield a succession of delights that a shorter meal could never contain.

At other times, though, the consumer of such a meal may feel as much like a victim as a guest. The reservation is hard won, the night is exhausting, the food is cold, the interruptions are frequent. The courses blur, the palate flags and the check can shock.

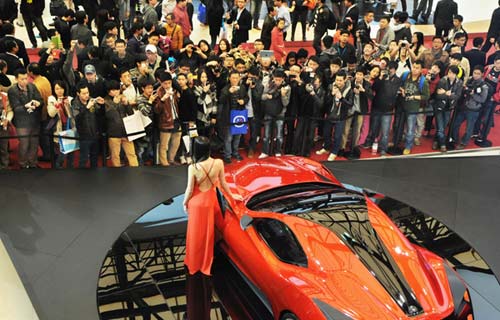

Across the United States, expensive tasting-menu-only restaurants are spreading like an epidemic.

This year in New York, two such places were born, Atera and Blanca, while two other restaurants, Eleven Madison Park and WD-50, dropped their o la carte menus in favor of all-or-nothing tastings.

Many of these restaurants are hits, with long waiting lists for their limited number of seatings. They have been hailed by critics.

A high-end anomaly a few years ago, three- or four-hour menus now look like the future of fine dining. It's worth asking if this is the future we want.

The kind of tasting menu that I refer to is a free-form invention, first made popular at destination restaurants like the French Laundry, Per Se, Noma and Alinea. Being so new, the genre has no rules and few limits.

This is a challenge no chef should saunter into casually. A restaurant whose sole product is an expensive, lengthy, take-it-or-leave-it meal sets a high standard for itself. And a few of them meet or exceed it with grace and agility.

At Benu in San Francisco, Corey Lee's menus are breathtaking explorations of the potential for treating Asian flavors with a modern American sensibility, and the look and flavor of each fresh course are surprising.

In New York, Cesar Ramirez of the Chef's Table at Brooklyn Fare has an almost supernatural gift for seafood cookery and noncookery, assembling meals that build from a salvo of sashimi-like bites to more complex hot dishes. Technical mastery and a sensitivity to nature's forms distinguish Matthew Lightner's tastings at Atera in Manhattan.

The tasting menu reaches what may be its most sophisticated American form at Alinea in Chicago, where Grant Achatz composes meals that are almost like symphonies.

In other cases, though, the patron struggles. When I face a marathon of dishes chosen by the restaurant, I often feel the same trapped, helpless sensation.

During an epic evening at Saison in San Francisco, I was often amazed by the way Joshua Skenes coaxed extra flavor from his ingredients through ancient means like dry-aging, curing, fermenting, smoking and grilling over fire. But some of the courses, more than 20 in all, were repetitive in ingredients or preparation, and others felt like padding.

The shapelessness of certain tasting menus might be blamed in part on a broken feedback loop. A restaurant that sells appetizers, main courses and entrees quickly learns which ones customers like. But one-bite dishes rarely come back to the kitchen untouched, so the chef has little chance to learn what customers think.

These restaurants can deviate from old-fashioned notions of hospitality in other ways. The ideal of serving a hot meal has been increasingly a lost cause, given how quickly a morsel the size of a cat's tongue will cool.

Tasting menus have made some of the country's greatest restaurants into luxury goods. A meal at the Chef's Table at Brooklyn Fare is now $225; it was $135 at the beginning of 2011.

Everybody knows how much a plate of chicken should cost in a fancy New York restaurant, but what is the value of 30 courses you haven't seen yet? You're not buying 30 courses, of course. You're buying a ticket to a show that is probably going to sell out, which leaves the restaurant free to charge scalper's prices.

And the elite who now fill these dining rooms are a particular kind of diner, the big-game hunters out to bag as many trophy restaurants as they can. As a result, a monoculture of earnest foodies has replaced the old biodiversity in which senior partners taking out the sales team from Atlanta would sit next to couples on blind dates. You can't eat a meal like this with a passing acquaintance since you'll be together for hours, but you can't go with somebody you really want to talk to, either, since there's little time between courses.

Once in a while, I've had tasting menus so extraordinary that none of these things mattered. But the format presents hurdles for customers and restaurants, enough to cause us to wonder how many more meals like this we need.

Not every novel should be "War and Peace." Sometimes, enough really is enough.

The New York Times

(China Daily 11/18/2012 page9)

Today's Top News

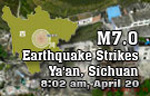

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|