All change, except the weather

Updated: 2012-03-12 10:57

By D J Clark (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

|

Children play in the school yard at Fuzhou Bay Central Primary School, Liaoning province. Photos by D J Clark / China Daily |

|

|

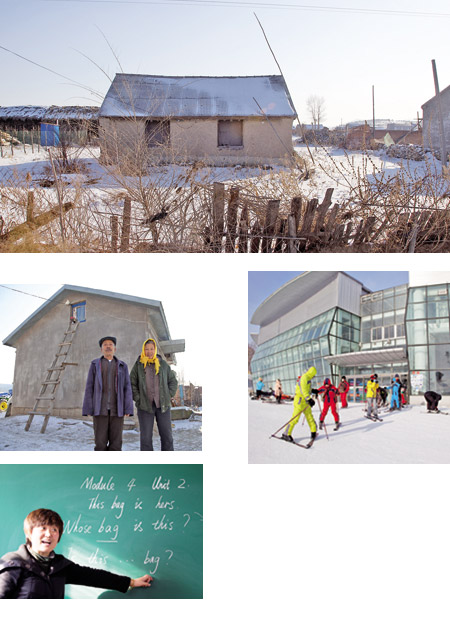

Clockwise from top: An old house made with mud and straw in Xinjia village, Jilin province. Modern farm buildings have replaced most of these old houses. Qingshan village has been transformed from a small farming community into a skiing destination. English teacher Zou Wenwen has witnessed improvements to teacher training and classroom technology. Shan Jixian with his wife Zhao Guangzheng live in a two-room house in the middle of Qingshan village, Heilongjiang province. |

Thirty years of rural development in the frozen Northeast has improved the lives of those living in villages, especially their finances. D J Clark reports in Northeast China.

It's -25 C as I get out of the taxi and start walking up Qingshan village's main street. Built in 1964 as a farming outpost in Heilongjiang province, the first settlers that braved the frozen winters had a very different life to the villagers of today.

Qingshan marks the starting point of a nine-week journey that will take me through China to find out how 30 years of rural development has impacted on the lives of an estimated 800 million Chinese spread out over 1 million villages.

According to recent government statistics, the number of people living below the poverty line in rural areas declined from 250 million in 1978 to 27 million in 2010. I am expecting to find many changes.

As I make my way up the long snow-covered street, retired farmer Shan Jixian sees me struggling to operate my camera with frozen hands and invites me in for tea. Sitting with his wife, Zhao Guangzheng, in a two-room house he reminisces.

"We are an old couple but we eat better now than we used to. In the days of community living, people who worked hard had just about enough food, but those who did little never had enough."

As I leave Shan's home and return to the biting wind, he takes me to the yard to show me a tractor he bought in 2011.

"This makes a big difference to our lives," he tells me as we shake hands and I feel his rough palms carved out by years of toil on the land. His grandchildren, it seems, are going to have it a lot easier.

Before reaching the end of the street I am once again invited into someone's home, the farmer Han Zhicheng, who has turned his family home into a guesthouse for hikers and skiers.

"After skiing came to this village we started to have a good life," he says as he barks instructions at family members who bring me tea and wipe a table.

Qingshan's geography has many disadvantages but the mountain that rises behind, combined with 170 days of snow a year, makes it ideal for skiing.

The provincial government recognized the potential 20 years ago when they chose it as one of 100 locations to build new resorts as part of a drive to develop the countryside through tourism.

The resort has grown over the years and now attracts over 100,000 visitors a year from all over the world. As an agricultural province with 46 million sq km of spectacular natural resources and over 20 ethnic group communities, the Heilongjiang government claims rural tourism has been a central part of its campaign to better the lives of the rural poor.

Taking a train south from Heilongjiang, then a bus and a 20-km car ride out into the far reaches of Jilin province, I arrive at Xinjia village.

It's -17 C as I step out of the car and am greeted by Guan Xishan, a music and PE teacher in the village school.

It's Saturday so the school is empty but Guan shows me a new building and computers and desks donated by the Changsha Shangri-La hotel.

"After reform and opening-up, people are very happy with the policy of enriching the people," Guan enthuses. "Like the rural pension, endowment plan, cooperative medical care, and the removal of the agricultural tax, it all means we have much more money these days."

We walk out of the school and turn down a frozen main street. Half way down the street we meet some passing farmers who laugh as they tell me things are improving for them but people in the city have better lives.

According to the 2010 China census, 51 percent of the population lives in villages in China. This figure has been slowly falling, down from 64 percent in 2000 and over 95 percent in the 1920s. It is likely that by 2015 there will be more people living in cities than there are in the countryside.

I am surprised by the size and structures of the buildings in Xinjia, many with animals and corn stacks in the front yard.

Guan explains how all the mud and straw houses have been knocked down and rebuilt with modern materials, along with new government supplied toilets.

I choose one house at random and ask the owner if I can have a look around. The Sun family shows me a large modern detached bungalow they built recently for 100,000 yuan ($15,800).

"This is much better than the previous house I had," Sun proudly tells me, explaining how his increased farm income, combined with money given to him by his son working in the city, meant he could save for the construction.

The Jilin government recently announced it aims to double the average rural income in the coming five years, in a bid to narrow the gap between rural and city dwellers. Money is an issue for everyone I speak to.

"There are many ways to earn money, now even corn fetches a good price. A large farm can earn as much as 100,000 yuan a year. Farmers can earn money through a variety of means, such as raising cattle, growing crops and building greenhouses for vegetables," Guan says.

"Some people choose to go to the city to work instead and they rent their land out to other farmers, making it more efficient to buy machinery."

Continuing my journey south to Liaoning province, I drive three hours out of Dalian, along the rugged coastline to Fuzhou Bay.

I am late arriving at the central primary school where I had promised to help teach an English class in return for a tour of the village.

As I enter the class Zou Wenwen is in full flow, entertaining the children with energetic movements around the room and an engaging smile. Halfway through she switches from the chalk and greenboard to an interactive whiteboard clicking through an entertaining powerpoint.

"There is a big change in this place. Before we taught with a single book, one tape recorder and by speaking. We did not have even flash cards and students got bored with the classes," she says during a break.

Five years ago, the Ministry of Education prioritized rural education, as the gap in standards between city and village schools appeared to be growing. Funding to rural schools almost doubled with a priority placed on water, electricity, heating, staff training and multimedia facilities, all of which had clearly reached Fuzhou Bay.

The latest official figures claim 99 percent of all children in rural China now attend primary school. But the number of those students reaching top universities continues to fall as competition from their city counterparts intensifies.

Earlier this year the Ministry of Education again increased its rural education spending by 20 percent to 48 billion yuan ($7.6 billion) with the target of continuing to improve the nine years of free compulsory education in the villages.

For Zou, who grew up in the village, teaching is not the only thing that has changed.

"When I was a kid, I walked or biked to school. Now each family has a motorcycle, some have their own cars. Family conditions are more prosperous now."

Today's Top News

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|