Litmus test of food safety

Updated: 2011-10-13 07:50

By Cheng Anqi (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

|

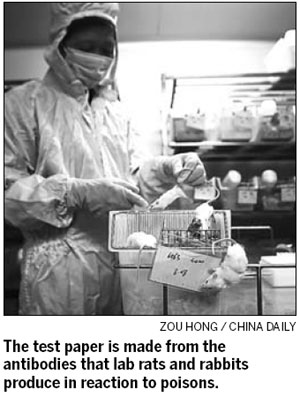

He Fangyang's food testing kits are widely used, including at the Beijing Olympics in 2008. [Zou Hong / China Daily] |

Given the nation's food scandals in recent years, a quick, relatively cheap and effective testing kit is timely and reassuring. Cheng Anqi reports.

When He Fangyang tried in 2002 to tell food companies that his food testing invention was reliable, none of them was convinced. "They put their faith in overseas testing machines and were doubtful of the efficacy of a 5-cm-long test paper," He recalls.

Although cold-shouldered by the food companies, the 42-year-old He persisted and eventually won over clients.

Over the past decade, He and his Beijing-based biophysics company, Kwinbon, have developed more than 100 kinds of rapid food safety detection solutions.

When his test paper is dipped in tainted milk, melamine can be detected in just three minutes, as two bars on the paper turn red.

Clenbuterol, better known as lean meat powder, can be detected when the test paper is dipped in pig's urine. The substance was officially banned from livestock farming in 2002 but continues to crop up.

Now, He is working on using his test paper to detect reconstituted oil at his five-story laboratory, where 5,000 lab rats and 100 rabbits are kept in cages.

The animals are administered poisons and the test paper is made from the antibodies they produce in reaction to this.

It was the tainted milk scandal of 2008 that was the impetus for He's interest in developing the melamine detection paper.

He's test paper soon hit the market.

|

"The raw milk we buy from dairy farmers is unsterilized, so large quantities of milk had to be tested for melamine and drug contamination before being refrigerated," says Xu Bingyou, laboratory director of Sanyuan Group, a collection of State-owned agriculture and animal husbandry companies.

"The test paper can greatly speed up the testing process to 10 minutes, from three to four hours," Xu says.

Just 10 years ago the food testing market was 85 percent controlled by foreign companies, says Yan Weixing, deputy director of the National Institute of Nutrition and Food Safety under the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

"Most food processing enterprises harbored doubts about the efficiency of domestic food detection kits," Yan says.

He formerly worked as a doctor at a coalmine in Guizhou province after graduating from Guiyang Medical University in Guizhou.

To pay his postgraduate tuition fees, he sold bean sprouts and bread on the street. In 1997, the biophysicist went to China Agricultural University (CAU).

While doing fieldwork at laboratories such as the State Laboratory for Tumor Cell Engineering at Xiamen University, He realized that traditional testing was costly and time-consuming.

"Normally, it takes two days or more for complicated food tests and it costs more than 3,000 yuan ($464) each time, " he says. "If companies turn to imported test kits, the price soars up to at least 3,600 yuan ($557) per kit."

This made He realize there was a gap in the market for cheap and effective testing devices.

Along with some college friends he rented a three-bedroom house in Beijing's suburbs and delved into the study of test kits for agricultural products and livestock shipments.

To gain more experience and accumulate funds they went to various science academies, where projects were outsourced.

His first client, in 2002, was a pork-processing unit in Hebei province, which bought five boxes of test paper used for lean meat powder detection. It earned him 7,500 yuan ($1,160).

When China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001 the requirement to meet quality standards and food safety laws became stricter. Seafood, in particular, was an issue.

"It might take days for the seafood to be tested at Customs, and in this time the consignment would go bad," he says.

The need for quick, cost-effective and accurate testing was crucial and this provided He with his opportunity.

His testing kits became widely used and were also adopted to ensure food safety at the Beijing Olympics in 2008.

He is now working on testing kits that ordinary people can use to "enable housewives to detect the potential health hazards of food".

Zhu Yi, associate professor at Institute of Food Science and Nutrition Engineering of CAU, says Kwinbon impressed her when she visited the company's laboratory.

"The test kits are competitive and affordable for many small food companies. If a food company has them it will provide reassurance for consumers," she says.