Society

Spineless creatures with minds of their own

Updated: 2011-06-19 07:45

By Natalie Angier (New York Times)

|

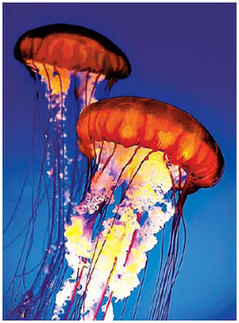

Jellyfish are not passive floaters. Researchers now say that they have complex nervous systems. Spotted lagoon jelly; below, Pacific sea nettle. Photographs by George Grall / National Aquarium |

An invertebrate with 24 eyes and a killer sting

Baltimore

Among multicellular creatures, jellyfish seem like the ultimate other. Where is the head, the matched sets of organs, the bilateral symmetry?

Yet jellyfish, a diverse group of thousands of species of invertebrates found worldwide, are among the first animals, dating back 600 million to 700 million years or longer. That's roughly twice as old as the earliest bony fish and insects.

"Jellyfish are the most ancient multiorgan animal on earth," said David J. Albert, a jellyfish expert at the Roscoe Bay Marine Biological Laboratory in Vancouver, British Columbia.

Jellyfish have long been ignored by science, dismissed as mindless protoplasm. Now, researchers are finding they have far more complexity. In the May 10 issue of Current Biology, Anders Garm, who studies jellyfish at the University of Copenhagen, and his colleagues describe the astonishing visual system of the box jellyfish, with an interactive matrix of 24 eyes of four distinct types - two very similar to our own - allowing the jellies to navigate through water.

And in the journal Experimental Biology, Richard A. Satterlie, a marine biologist at the University of North Carolina Wilmington, disputes the conventional wisdom that jellyfish lack a central nervous system. Studies reveal evidence of "neuronal condensation," places where the neurons coalesce to form structures that act as integrating centers - taking in sensory information and translating it into the appropriate response.

"Jellyfish do a lot more than people think," said Dr. Satterlie, adding that the claim they have no centralized nervous system is "flat-out wrong."

Dr. Albert insists that a jellyfish has a brain. In studying moon jellies in Roscoe Bay, he discovered that they are not passive floaters. When the tide flows out, they ride the wave until they hit a gravel bar, and then dive down to reach still waters. They remain there until the tide starts flowing back in, when they rise and get swept back into the bay. He also learned that the jellies have salinity meters to avoid the fresh water deposited by mountain snowmelt. And they like to form schools.

"If a moon jelly gets touched by a predatory jellyfish, it turns and swims up," Dr. Albert said.

"These are not simple reflexes. They're organized behaviors," he said.

"That's what a brain does," he added. "It controls behaviors."

At the National Aquarium here, the jellyfish exhibit includes specimens that look like beating hearts, others that resemble spotted toadstools, and still others like parasols with ruffled streamers.

They're mesmerizing to visitors - a good thing, because the infrastructure needed to keep them can cost millions of dollars. "Keeping jellyfish," said Vicky Poole, the exhibit manager, is "a little like maintaining phlegm."

In the wild, jellies are found in open oceans, along coasts and in lagoons, and a few can handle fresh water. With their modest oxygen requirements, jellies can grow in post-algal "dead zones" and other polluted waters where most marine life can't - not surprising for a group that has weathered five past mass extinctions.

Jellies range in size from the fingernail-size Australian Irukandji to the lion's mane jelly, with a bell 2.5 to 3 meters wide and tentacles trailing 30 or more meters.

A hallmark of jellies, their radial symmetry, allows them to swim or drift in straight lines.

All jellies are carnivorous, and they use their tentacles as drift nets. Should a fish brush against them, stinging cells release tiny harpoons packed with neurotoxins. In the most venomous jellyfish, the toxins work quickly.

"If a jellyfish were to swallow a prawn that wasn't completely dead," said Dr. Garm, "the prawn would puncture its stomach." Some of the poisons, like that of the sea wasp, an Australian box jelly, can kill humans in seconds. But because the harpoons are so shallow, swimmers can protect themselves by covering their skin with pantyhose.

In their new report, Dr. Garm's team studied box jellies' complex battery of eyes. Not only do they have a cornea, lens and retina, but they are suspended on stalks anchored by heavy crystals.

"The crystal works as a weight," Dr. Garm said. "No matter how the jellyfish reorients itself, the stalk bends and the eyes face up."

The researchers determined that the jellyfish, which feed in murky mangrove swamps, look upward for navigational guidance. Every night, they are swept away from the trees and sink to the bottom. Every morning they must return or risk starvation. As they rise, their upturned eyes scan the sky, until they spy the mangrove canopy, and they start swimming home.

The New York Times

E-paper

Pret-a-design

China is taking bigger strides to become a force in fashion.

Lasting Spirit

Running with the Beijingers

A twist in the tale

Specials

Mom’s the word

Italian expat struggles with learning English and experiences the joys of motherhood again.

Lenovo's challenge

Computer maker takes on iconic brand apple with range of stylish, popular products

Big win

After winning her first major title, Chinese tennis star could be marketing ace for foreign brands