Society

Crafting a revival

Updated: 2011-02-09 08:16

By Huang Zhiling and Hu Haiyan (China Daily)

At dawn one sees this place now red and wet; Flowers are numerous in the brocade city, is He Bin's favorite line from a verse by Du Fu (AD 712-770), one of the greatest Chinese poets, who lived during the Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907).

|

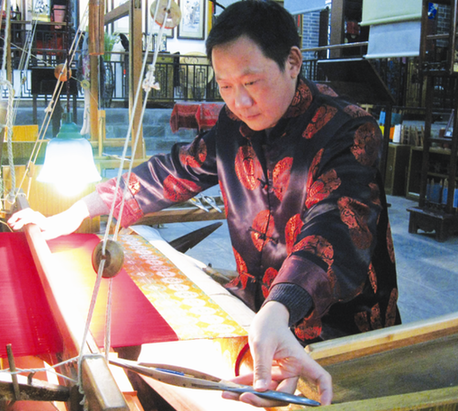

He Bin, 46, is among the few master Shu brocade weavers in Sichuan province, hometown of the 2,000-year-old craft. Photos by Hu Haiyan / China Daily |

The 46-year-old Shu brocade master weaver says the verse reminds him of his 2,000-year-old craft, but he's worried about its future.

"When I read this verse, I sense the beauty and delicacy of Shu brocade. It also reminds me of my past 29 years doing it," He says.

"In the late Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), Chengdu had more than 2,000 private workshops and more than 10,000 looms producing brocade. But today, the number of master weavers can be counted on two hands," He says.

In 2006, Shu brocade weaving techniques were included on the list of China's Intangible Cultural Heritage by the State Council.

It often takes an entire day to weave between 5 cm and 6 cm of Shu brocade.

"I once spent one week finishing a brocade piece the size of a small handkerchief," He says.

"Because of the dull routine and low pay, few young people want to be brocade weavers now and the passing on of the craft faces great difficulties."

He currently works as a technician at the Shujiang Brocade Academy in the city's western suburbs. Opened in 2003, the one-story building also serves as a makeshift museum where visitors can get a basic idea of Shu brocade history and buy silks.

"Brocade weaving techniques require learners to know about silkworms and silk, which is another difficulty when it comes to selecting students of the craft," says Cai Jing, manager of the marketing department of Shujiang Brocade Academy.

Shu is the oldest school of brocade making, from which the others developed. These include the Song brocade of Suzhou in Jiangsu province, the Yun brocade of Nanjing in Jiangsu province and Zhuang brocade from Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region.

The history of sericulture, or silk farming, in China, can be traced back to Sichuan more than 4,000 years ago. Known as Shu in ancient times, Sichuan is one of the cradles of China's silk industry.

In the Warring States Period (403-221 BC), Shu brocade became a major export and Chengdu's silk products were exported across Asia.

Today, Chengdu is still called "Brocade City" and the moat where finished brocade used to be soaked to set their colors is still known as Brocade River.

Even so, the development of Shu brocade faces many challenges.

|

Artisans work on looms to weave Shu brocade at the Shujiang Brocade Academy in Chengdu, Sichuan province. |

Apart from the difficulty of passing on brocade weaving techniques, shanzai, or counterfeit Shu brocade, also hinders real Shu brocade development.

"Most customers lack the necessary knowledge about Shu brocade, and it is hard for them to tell the real from the fake," Cai says.

"The average piece of brocade with a traditional design takes seven to eight months to do and when finished is truly a work of art. More complex weaves can take even longer," Cai says. "Shanzai Shu brocade, on the other hand, is produced large scale and at a much faster speed."

"Although the shanzai Shu brocade is similar to the real brocade in appearance, it is inferior in terms of material, design and craftwork," Cai adds.

"The lack of standards in the brocade industry is an important reason for shanzai Shu brocade flourishing," Cai says. "The Shujiang Brocade Academy is now collecting and compiling information to set up industry standards. When finished, it will be sent to the responsible government agencies for approval."

The high price of Shu brocade is another obstacle for its market expansion. "Because it takes time to weave, in ancient times, a fine piece of Shu brocade was as expensive as gold. Even today, the price of a Shu brocade is much higher than other common handicraft works," He Bin says.

A typical Shu brocade wall hanging, 1 meter in length and 80 cm in height, costs about 10,000 yuan ($1,470), He says.

To gain more market share, Shujiang Brocade Academy has launched new types of brocade that can be used for interior dcor and as a trimming on luxury goods, in addition to handkerchiefs, purses and scarves.

"To enable Shu brocade to develop further, more government support is required," Cai says. "Compared with Yun brocade in Jiangsu province, Shu brocade gets less government support."

"Despite these challenges, the development of Shu brocade weaving is still full of hope," Cai says.

Shujiang Brocade Academy has raised 30 million yuan ($4.4 million) to set up the Chengdu Shu Brocade and Embroidery Museum.

The museum will inform visitors about the history of the South Silk Road 2,000 years ago and displays carvings depicting the 12 processes for silk production. It also has jacquard looms and representative Shu brocade works from various dynasties, as well as modern brocades of giant pandas, silk dragon robes, silk purses, bags, quilts, ties and name-card holders.

"After opening the museum, Shu brocade will be more accessible," Cai says.

"We also plan to explore the overseas market, especially the US."

E-paper

Ear We Go

China and the world set to embrace the merciful, peaceful year of rabbit

Carrefour finds the going tough in China

Maid to Order

Striking the right balance

Specials

Mysteries written in blood

Historical records and Caucasian features of locals suggest link with Roman Empire.

Winning Charm

Coastal Yantai banks on little things that matter to grow

New rules to hit property market

The State Council launched a new round of measures to rein in property prices.