Sanmao, the hero with a heart

It was their hairstyles or headgear as much as anything that gave them instant recognition.

First, in 1928, the mouse with erect black ears and a semi-permanent grin made his grand entrance.

Then, the following year, came the youngster with the golden locks with a swished-back clump standing up in the middle of it all.

In 1934, the duck with a sailor's hat and shirt and a red bowtie said hello to the world.

The following year, the lad with three solitary strands of hair on an otherwise bald head shuffled onto the stage, the hair and his two bare feet signaling that for him, unlike the other three characters, life was to be endured rather than enjoyed.

The wonder of all this is that more than 80 years after these characters first appeared - the Americans Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck, the Belgian Tintin and the Chinese Sanmao - they are still with us, aging yet ageless, and the great amusement they gave us has left its mark on billions of people worldwide.

But beyond that fun, delivered through comic books, on the big screen and on television, these characters have at times had a serious underside. In fact, in the book How to Read Donald Duck, first published in Spanish in 1971, and which became a best-seller in Latin America, Ariel Dorfman and Armand Mattelart depicted Disney comics as tools for spreading Western capitalism. As for the brave and adventurous Tintin, his first outing in the world was in a work titled Tintin in the Land of the Soviets, which could not have been more political.

In Sanmao, a world away from the assertive, well-to-do, swaggering and happy-go lucky often present in Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck, the seriousness lay in other directions.

His story is that of an orphan who moves to Shanghai to earn a living. He takes on numerous jobs, such as selling newspapers, polishing shoes and performing kung fu. Despite his efforts, he cannot make ends meet, sleeping on the streets, and many treat him with disdain.

Nevertheless, he is always keen to extend a helping hand to the less fortunate, to the point of giving whatever little food he has to beggars. He is also highly ethical, evidenced in one case by his refusal to join a gang of thieves who pledge that if he does join, he will be well fed and looked after forevermore.

Sanmao, which means three hairs, was created by the late Zhang Leping, one of China's most acclaimed comic artists, and this year marks the 70th anniversary of the most successful Sanmao comic book, The Winter of Three Hairs, which had a print-run of more than 10 million copies. It is also listed as one of the 100 must-read books by China's Ministry of Education.

Zhang was born in Haiyan, Zhejiang province, in 1910, and his early life was marked by the kind of hardships Sanmao would go through. The earnings of his father, who worked as a primary school teacher, were barely enough to support a family of six, and life became even harder for the family on the death of Zhang's mother when he was 9.

After completing primary school, he was forced to work to support the family. He first worked as an apprentice in a wood factory before finding a job in a printing plant in the suburbs of Shanghai in 1923, and about this time he took on several short-term jobs. He said that many of the bosses he worked for were demanding and cruel, often beating up employees. These men are depicted in The Winter of Three Hairs.

In those days, beating up apprentices was regarded as essential in producing the best artisans, and Zhang would later tell of how he despised it. Over several years he taught himself to draw and paint, and after having several drawings published in newspapers, he began to gain a reputation as an accomplished comic artist.

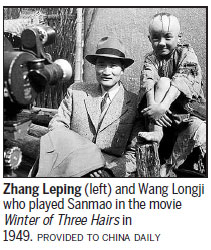

When he created his first cartoon of Sanmao in 1935, it depicted a boy living in a typical lane house in Shanghai. During the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression (1931-45), the story of Sanmao was based on Zhang's experience as a member of the resistance. After the People's Republic of China was founded in 1949, Sanmao's life would take a turn for the better as he went to school and studied science.

The newspaper Ta Kung Pao in Shanghai published its first comic strip from The Winter of Three Hairs on June 15, 1947. It comprised six pictures depicting Sanmao's sadness about not having parents. Over the course of the next two years, the comic strip became well known throughout the country, and how much the public warmed to Sanmao was evident in the response that his plight drew.

"Sanmao is living on the street," one furious reader wrote to the publisher. "Why can't you treat him better? I'm willing to put him up in my home."

In 1949, Soong Ching-ling, the wife of Sun Yat-sen, wrote: "Mr Zhang has done a great deed for homeless children, and we appreciate that. All Sanmaos in the country will never forget this."

The artist Dai Dunbang said the comic strips seemed to come alive because of the way Zhang drew the characters and how he introduced fine differences in various backgrounds.

A movie based on the comic book premiered in October 1949, the first public movie in the newly founded People's Republic of China, and it gained wide acclaim.

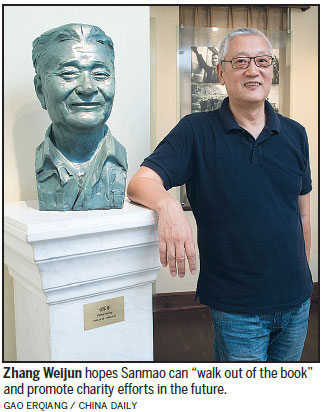

Zhang Weijun, 63, the youngest child of Zhang, who died 25 years ago, says most of the comic series reflected his father's life.

Zhang Weijun promotes the comic, and countries in which he has helped organize exhibitions of Sanmao in recent years include Australia, Belgium, Mauritius and South Korea.

Zhang says his father came across three homeless children on a snowy night in Shanghai in 1947. The children, dressed in worn-out clothing, wrapped themselves in sacks to stay warm and gathered around a small iron can that held a fire, he said.

The next morning, he saw the frozen corpses of two of the children being loaded onto a vehicle.

"That incident shocked my father and led him to create The Winter of Three Hairs."

From 1927 to 1949, China was in chaos because of civil conflict, the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression and natural disasters, and this resulted in millions of refugees pouring into bigger cities such as Shanghai.

To find out more about how homeless people lived, Zhang Leping went to Chen Jia Mu Qiao in Shanghai, where such individuals gathered, but nobody would talk to him, Zhang Weijun says.

"One of these people treated my father with contempt, and that upset him. My father later realized the problem was his suit. For the poor, anyone who wore nice clothes was rich - the very people who often bullied and humiliated them."

The artist then began wearing threadbare clothes and giving out pies to the homeless, and gradually, the children started warming to him.

The episode about a beggar urging Sanmao to become a thief was, like other episodes, based on a story these homeless children told him. In those days, homeless children would often resort to helping gangsters steal in exchange for food.

While Sanmao was someone many loved, the artist himself had one or two detractors.

"My father once received a letter accompanied by a bullet," Zhang says. "He thought it might have been a threat from local ruffians, because the way he depicted gangsters in the comic strip, as nasty and greedy, showed how much Sanmao despised them."

Because they loved children so much, Zhang Leping and his wife, Feng Chuyin, who had seven children, helped raise several children of friends and relatives who could not afford to.

Zhang Weijun says his mother always used the family's biggest pot to prepare rice every day for friends and relatives. The family would often house homeless orphans as well.

The late artist was also passionate about drawing for children. In his last years, when he had Parkinson's disease, he wrote: "My only pain is that my shaking hands can't paint for young readers anymore."

He also expressed his regret at the imperfect drawings he had done for a series titled Sanmao Eats Watermelon, made public before Children's Day in 1989. Nevertheless, the artist received many letters from his young readers praising him for his dedication and expressing hope that he would recover soon.

When he died in Shanghai in 1992, he was 82.

With the help of the Xuhui district government last year, the Zhang family vacated their residence and turned it into a memorial gallery. In the days after its opening, thousands of Sanmao fans lined up in the streets, waiting to view the original scripts, drawings and videos related to the comic series it features.

The artist's study, kept in its original condition, can also be viewed.

"I am a little surprised to see that Sanmao can still win the hearts of readers of various ages today," Zhang Weijun says. "Young parents are still buying Sanmao books for their children as their parents used to do for them.

"Poor children like Sanmao hardly exist in Shanghai now, but people can still identify with his optimism and his willingness to help others.

"Once when I was visiting my father's grave, an official told me a man from northern China had spent a long time there. He said that once, in his most difficult time, my father had helped him."

xuxiaomin@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily European Weekly 10/13/2017 page1)