Between a hangover and going cold turkey

Updated: 2014-03-21 08:16

By Giles Chance (China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||||

Doom-laden prediction of economic slump overlooks some important facts

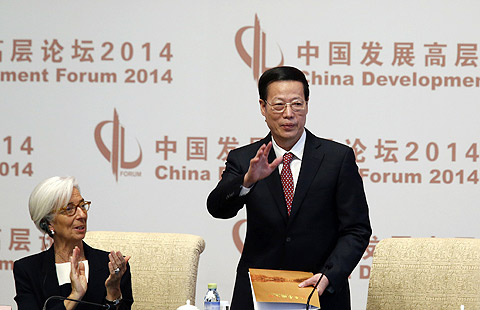

In his new book Avoiding the Fall: China's Economic Restructuring, my colleague Guanghua professor Michael Pettis forecasts a collapse in annual Chinese economic growth rates over the next decade to low single digits (2-4 percent). This projection is based on the idea that China will need a period of well-below-par growth in order to allow its economic imbalances to correct themselves.

Pettis, who correctly judged several years ago that China's growth would become a matter of central global importance, started to broadcast his contrarian growth message in the face of the widespread and overwhelming China bullishness following the Western financial crash and the Beijing Olympics in 2008. More recently, as the China euphoria has started fading, and the message of gloom has gained strength. As the Chinese economy shows signs of further slowing, is he right?

Pettis' case of doom has been built on excess - excessive saving and excessive investment spending, driven by excessive growth in debt. To a degree he is right. In mid-2008 the Chinese government, fearing the worst, injected the largest economic stimulus yet recorded, more than 12 percent of GDP, entirely via increased government spending. Up and down China, local governments rejoiced at what they called "the last supper", which they saw as the last chance they might get to start their favorite projects and repay local favors.

By mid-2009, anxious economists worldwide sat back in relief as they saw China's growth pick up in response to the flood of new orders for steel, cement, electrical cabling and other building products. The surge in government spending and, just as importantly, the surge in confidence that followed, kept the Chinese and global economies afloat, at a time when the whole world might have fallen into a deep depression.

Clearly, China's "last supper" had to end sometime. But what Pettis argues is that the hangover will be worse than recovering from a night on the town. His central argument is that China's high savings rate supports an unsustainable spending splurge at home, and an unsustainable current account surplus abroad. Both these bulging imbalances must deflate, he argues, and the quicker they deflate, the lower China's growth rate has to go.

Where I disagree with Pettis is on his diagnosis. I don't believe that all of China's infrastructure spending has been wasteful, as he claims. China, as we all know, is an enormous and developing country. A huge building program that provides basic essentials is what much of China desperately needs. In that sense, important benefits have flowed from "the last supper". We can expect much of the new road, energy, housing and communications infrastructure to support higher long-term levels of economic activity. In my opinion, Pettis ignores the considerable economic benefits that will flow from the stimulus plan.

Neither do I agree with him that China's current account surplus, now running at between 2 percent and 3 percent of GDP, must inevitably rebalance to zero. China's savings rate will decline as its population ages, but this will only happen slowly. Meanwhile, until this happens, the world can easily support a modest Chinese external surplus, and the capital outflows that accompany it.

What about the waves of non-performing loans that will follow from the boom in wasteful infrastructure spending? I don't believe that much of the infrastructure spending will turn out to be a write-off. However, a vital part of maintaining economic growth will consist of recognizing bad loans if they appear, writing them off, and raising fresh capital if necessary. We have already seen a new round of Chinese bank fund-raising through equity issues. More new capital may be necessary. But given the close attention that the Chinese bank regulator has paid in recent years, I do not expect that the country's banks will run into major solvency problems.

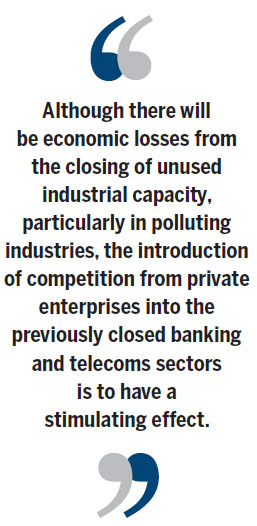

An important unknown, which Pettis glosses over, is the speed with which China's market-based reforms will start to add to economic growth, via increases in employment and consumer-based spending. Although there will certainly be economic losses in China from the closing of unused industrial capacity, particularly in polluting industries such as steel and aluminum, the introduction of real competition from private enterprises into the previously closed banking and telecoms sectors is bound to have a stimulating effect, as it did 30 years ago in the United States and Europe when deregulation was introduced.

Pettis has performed a valuable public service by emphasizing the weaknesses in China's growth model, which are real. But, in his anxiety to show his case to be overwhelming, he ignores some important factors. Over the one or two-year period of transition before the new reforms begin to bite and bring fresh growth, I expect China's growth will be supported by strong productivity growth in its efficient export sector and the increasing benefits that will accrue from its huge investments in transport and telecommunications.

The author is a visiting professor at Guanghua School of Management, Peking University.

(China Daily European Weekly 03/21/2014 page19)

Today's Top News

China, the Netherlands seek closer co-op

Crimea is part of Russia

Images may help solve jet mystery

Obamas wowed by China

Xi leaves Beijing for first trip to Europe

Beijing beefs up hunt for missing jet

Putin signs law on Crimea accession

Australia to resume ocean search for missing jet

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|