'Act before reaching tipping point'

Updated: 2014-03-21 08:16

By Andrew Moody (China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||||

|

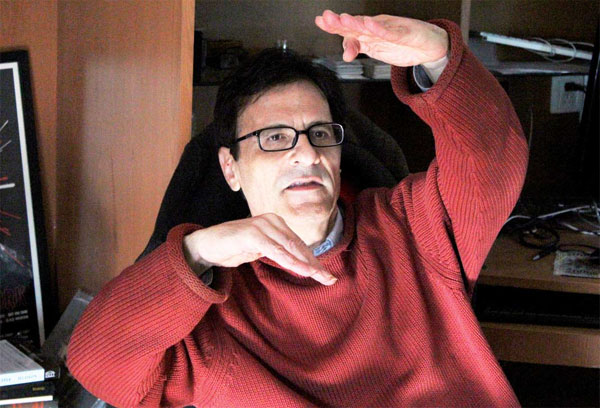

Michael Pettis says the Chinese economy could hit a wall within three years unless significant reforms are implemented. Wang Zhuangfei / For China Daily |

Finance professor stresses investment-led growth model is a danger to the Chinese economy

Michael Pettis believes China's investment-fueled economic model is running out of time.

The professor of finance at Peking University's Guanghua School of Management argues that unless significant reforms are implemented the Chinese economy could hit a wall within three years.

This could see GDP growth collapse from its current 7.6 percent and head toward zero.

"We have at most two or three more years of the (investment-led) growth without running into debt capacity constraints. We have to adjust before then," he says.

Pettis makes his arguments in his new book Avoiding the Fall: China's Economic Restructuring, which was selected as one of the top 10 economics books of 2013 by the Financial Times.

"The (current) model is over. Once you begin misallocating investment on a systematic basis it is time to switch to another growth model. History is not on China's side. No country has ever managed to switch in time. They have always waited too long to when debt levels move up to a very dangerous level."

Pettis was speaking in his office above XP, a Chinese independent music venue near Hohai Lake in Beijing, which he also owns and operates as a sideline to his day job.

The 55-year-old American, who grew up in Spain, says the worry for Chinese policymakers, who set out a comprehensive economic reform agenda at the Party's Third Plenum at the end of last year and at the National People's Congress and the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference earlier this month, is that it is impossible to gauge when an economy has reached the critical point.

"Once you reach that point things degenerate so quickly there is not much you can do about it. So you never want to reach a point when you know you have too much debt because usually by then it is too late."

The Chinese economic model, according to Pettis, has to change to one where consumption plays a bigger role in the economy and investment a much smaller one. In China at present, consumption makes up only around 35 percent of the economy, compared to 70 percent in the United States and around 65 percent in Europe. China's investment ratio of 50 percent is one of the highest in economic history.

Pettis says stress points are being reached because investment in infrastructure and other projects no longer produces a sufficient return to cover the cost of the borrowing.

As such, investment only serves to increase the country's debt levels. The problem has been made more acute by the 4 trillion yuan ($646 billion, 464 billion euros) stimulus package the government enacted in the wake of the financial crisis in 2009.

This has led to local government debt alone soaring 70 percent over the past three years to $17.9 trillion yuan, according to China's National Audit Office.

China's official debt to GDP ratio is 58 percent of GDP, according to the official figures, although some other estimates put it at 200 percent or even at 240 percent.

Pettis argues, however, that it is not the actual debt ratio statistic that might be crucial.

"We don't really know what the true ratio is but it is certainly very high. The actual figure is not the only thing that matters but also the structure and underlying volatility of the economy.

"If you take the case of Argentina in 2000, its debt to GDP ratio was only 50 percent yet at the end of 2000, they devalued the currency and in 2001 they defaulted on their debt."

Pettis is an acknowledged expert on the Chinese economy, and his latest book follows on the heels of The Great Rebalancing: Trade, Conflict and the Perilous Road Ahead for the World Economy, which also generated much interest.

A former Wall Street investment banker, he headed Latin American capital markets for Bear Stearns before he came to China in 2002.

"I was teaching at Columbia (University in New York) and I used that to get a teaching job in China and I figured that in two years I could learn enough about the country to return to Wall Street. I just like living here, apart from the air, and I have stayed 12 years," he says.

Despite speaking five other languages, including Urdu, Spanish and Portuguese, he has failed to master Chinese.

"I figure it is an opportunity cost. I am bad at learning languages so I can either spend two hours a day reading Chinese history or studying putonghua. I think I will learn much more from the former than the latter."

Pettis, a slightly bohemian figure, says that it is not a matter of choice about whether to rebalance the China economy since it will happen either through policy direction or by an inbuilt self-correction mechanism that all economies possess.

"You reach a point where investment collapses and tends toward zero. Consumption cannot fall by as much because people have to consume to survive. So the result is that consumption takes a bigger share of the economy than it previously did even though consumption falls in the process," he says.

In his book, he presents six rebalancing scenarios for the China economy, of which one is for the government to do nothing at all and continue with high investment rates until it hits its debt capacity limits.

Other measures include raising real interest rates to force up the value of the currency by 20 percent and push up spending by lowering income taxes; imposing the same measures but less drastically; embarking on a privatization program of state assets; letting the state absorb private sector debt; and finally, just cutting investment sharply.

"You can mix and match and I think they (the Chinese government) will. We have already seen debts being transferred off government balance sheets which has given them room to make other adjustments."

Pettis says the danger is falling into the trap of thinking that China has managed more than 30 years of continuous high level growth and so possesses some unique model that is incapable of failing.

"The problem with the 'this time is different' line or argument is that it never is. The point of this book is that this is the most dangerous phrase in economics."

He says it was a line rolled out before the financial crisis by those who thought the financial "masters of the universe" had solved the problem of economic cycles by using sophisticated financial instruments and more eerily perhaps for China by those commentating on Japan in the late-1980s.

"One of the things I tell my students is to read old magazines. If you take The Economist in 1988 and 1989 you get an article almost every issue saying how incredibly smart and efficient the (Japanese) government was and how it was changing economics. The result was 20 years of 0.5 percent growth."

Pettis says that if China did have a bust, growth might stagnate to zero for some time but would eventually return to a trend GDP growth of 6 to 7 percent at some point.

He actually predicts growth will average between 3 and 4 percent up to 2023, much lower than almost all other estimates.

"What I am hoping is that this year we break below 7 percent and next 6 percent and then we grow gradually down. I think that is sustainable. What would be worse is that if we had 7, 7, 7 and then 2. Something like that would be very painful," he says.

Some argue that Pettis does not take into account the huge potential that China has to grow through urbanization with only half of its population living in cities.

"The problem with that argument is that it has causality backwards. It says that urbanization causes growth.

"The reality is, however, that if you bring a worker from the countryside to Beijing and build him an apartment and other infrastructure but don't find him a productive enough job then that move is all cost and has no benefit to the economy. There are huge constraints to this process."

He says building skyscrapers, airports or roads is not a process that makes you rich.

"Development is not a function of capital stock. England is not richer than Bangladesh because it has more capital stock. England simply has more capital stock because it is developed," he says.

Pettis, who originally trained as a physicist and has a mathematics background, says the problem with economics is that it has been taken over by mathematicians who fail to take into account economic history, where the real lessons for China lie.

"We still don't have any great books on Chinese monetary history but I am encouraging my students and perhaps one of them will write the classic book."

andrewmoody@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily European Weekly 03/21/2014 page18)

Today's Top News

China, the Netherlands seek closer co-op

Crimea is part of Russia

Images may help solve jet mystery

Obamas wowed by China

Xi leaves Beijing for first trip to Europe

Beijing beefs up hunt for missing jet

Putin signs law on Crimea accession

Australia to resume ocean search for missing jet

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|