Sit the month

Updated: 2013-12-13 09:36

By Zhu Weijing (China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||||

The traditional postpartum custom observed in the middle Kingdom

When the Duchess of Cambridge Kate Middleton gave birth to a royal baby, she stepped out to greet the world's media the next day. Many Chinese looked on aghast: How can they treat her so cruelly? Do they not let her "sit the month"?

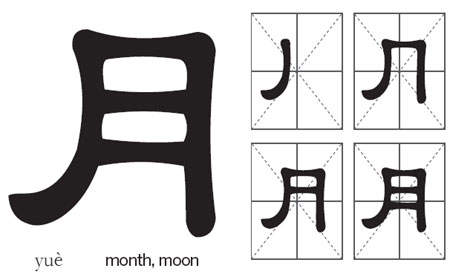

Sitting the month 坐月子 (zuòyuèzi), is a traditional postpartum custom observed in China and several other East Asian countries. It is a significant and strictly-observed month for a newly expanded family.

Just as many Chinese were bemused by Middleton's behavior, many in the West would find post-childbirth confinement in China absurd. Till recent times, most Chinese took this confinement quite literally and added a few dozen extra steps for good measure.

Some of the no-nos on the traditional list, even though most new mothers are unable, or unwilling, to observe them all strictly nowadays, include: no direct contact with the wind, no going out, no fruits, no vegetables, no salt, no wearing sandals, no exposing of the heels, no leaving empty space between the waist and back of a chair (cushion required), no hair washing, no baths, no brushing teeth, no brushing hair, no TV watching, no crying, no boiled water, and more. Everything from the food that goes into the mouth, to the air flow in the room - right through to the precise posture and exact amount of standing, sitting and walking - is closely monitored with military precision by various members of the family.

An old Chinese saying addresses the significance of postnatal care: "Eat well, sleep well, nothing is better than sitting the month well." (吃的好,睡的好,不如月子坐的好。Chī dē hǎo, shuìdē hǎo, bù rù yuèzi zuò dě hǎo.) The health aspects of zuoyuezi find support in traditional Chinese medicine. According to TCM, there are three crucial periods that have life-long effects on a woman's health: the first period, post-childbirth and menopause. It's believed taking the 月子 lightheartedly may result in 月子病 (yuèzibìng), a loose traditioanl Chinese medicine term referring to all illnesses contracted during the month after childbirth that never completely heal. While Western medicine explains the need for postnatal care in scientific terms, TCM attributes it to imbalanced yin and yang. From the perspective of the Yao medicine, yuezibing results from the invasion of the Six Evils (六邪 liùxié): wind (风 fēng), cold

(寒 hán), dampness (湿 shī), dryness (燥 zào), fire (火 huǒ) and heat (暑 shǔ). Hence, a new mother must receive 24-hour care lest any natural element leaves her in ill-health.

Although giving birth is a natural ability for a woman, the zuoyuezi period of intensive care used to be enjoyed by the husband of the mother. In his imaginatively titled Travels of Marco Polo, Marco Polo reports on a Dai (傣) ethnic custom: "As soon as a woman has been delivered of a child… her husband immediately takes the place she has left, has the child laid beside him, and nurses it for forty days." The husband would then be attended to by the wife, who also attended to household chores and breastfeeding. The Chinese call these men 产翁 (chǎnwēng, birth giving men), as opposed to 产妇 (chǎnfù, birth giving women), as not only did they go through zuoyuezi on behalf of the mother, sometimes they would even lie next to their wife while she delivered the baby, mimicking the process of childbirth.

More and more, Chinese are starting to question the old taboos of traditional zuoyuezi. With certain myths, they are right too. Some of the behaviors sound positively medieval; mothers cannot drink water or milk for two weeks after giving birth, substituting it for rice wine. Not bathing or washing their hair for a month is forbidden, as is salt - all the while consuming as much sugar and protein as possible.

Contrary to common belief, the concept of zuoyuezi derives not from traditional Chinese medicine but from ceremonial rites. The earliest documented practice of zuoyuezi is found in the Book of Rites (《礼记》Lǐjì). In the 12th chapter, the custom is described as a postnatal ceremonial family ritual that the new mother goes through, symbolizing the transformation of her role from wife to mother, from outsider to family member.

Consequently, some younger mothers are now denouncing the holy month of zuoyuezi as an outdated feudal practice that should never have made it to the modern era. But some mothers and mother-in-laws, however, still insist on enforcing old traditions. When new mothers pull out the "no one in Europe or America eats 30 eggs a day for postnatal recovery" argument, older relatives often argue it is because of racial differences. Some go so far to claim that not being scrupulous about sitting the month is precisely why Chinese age better than foreigners, or even that foreigners simply don't know any better.

But Western obstetrics and qualified physicians are becoming more common. Any many of the taboos are being logically explained away, including the ban on baths.

The restriction on taking baths was due to the bad sanitary conditions of the past, which could easily cause dangerous post-natal infections for new mothers; essentially, taking a bath was just not worth the risk.

Although medical science has proved many of these archaic practices unnecessary and even unhealthy, its influence decreases once patients leave the hospital and return to their mothers or in-laws who begin to peddle the old wives tales.

An extremely protein-heavy diet remains one of the most significant parts of the zuoyuezi care, and postnatal caregivers are hotly sought after, especially ones that are qualified, have experience, and possess both the knowledge and the cooking skills to produce a month-long yuezi food menu.

A spot at a quality postnatal care facility is more difficult to obtain than a reservation in heaven itself. Guo Jingjing, the retired Olympic diving champion, is offering HK$80,000 ($10,320; 7,600 euros) for a top-notch postnatal caregiver. Chinese actress Jia Jingwen's care giving center costs upward of 4,500 yuan ($740; 540 euros) per day, with the minimum stay being no less than 15 days.

The invasion of Western medicine firmly grounded in science may have shifted the views of many Chinese toward hospitalization and treatment, but it still has a some way to go before it fully soothes Chinese nerves or overtakes TCM and arcane folk beliefs.

Courtesy of The World of Chinese,

www.theworldofchinese.com

The World of Chinese

(China Daily European Weekly 12/13/2013 page27)

Today's Top News

Complacency hinders US energy-saving strategies

Beijing to reform pricing system for subway tickets

Vaccines suspended after deaths

China reports new H7N9 case

Chang'e-3 mission 'complete success'

Mandela laid to rest

Abe's checkbook diplomacy may fail

Finding people with right talent

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|