Reaching for the summit

Updated: 2013-07-26 11:03

By Andrew Moody (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

What China has to do to break out of the middle-income trap and reach developed-economy status

Can China break out of the middle-income trap? Many countries find the move from low to middle-income status straightforward but find the next step up a climb too far.

In his book, Breakout Nations: In Pursuit of the Next Economic Miracles, which has just been published in Chinese as well as paperback, Ruchir Sharma, head of emerging market equities at Morgan Stanley and leading economic commentator, makes the case that China alone among the BRICS nations will make it to the next stage.

He believes it will be able to move on from its 2012 per capita income level of $6,091, according to the World Bank, to around $20,000 within 15 years, making it comfortably high income.

He makes the point, however, that it will be easier for China to move up the ladder if it sets its growth targets lower at a more sustainable 5 to 6 percent.

Chasing higher rates of growth through excessive investment in infrastructure, he argues, carries the risk of a bust that could see it yo-yoing along in the middle-income trap like many other countries before it.

He paints a gloomier picture for China's fellow BRICS members. He sees Brazil, despite the opportunity to showcase itself by staging next year's FIFA World Cup and the 2016 Olympics, as indebted without a manufacturing base and likely to remain in the middle-income mire it has been stuck in for 40 years. Its per capita income was actually down nearly 10 percent on its 2011 level of $12,576 at $11,340 last year.

Russia, he argues, is entirely vulnerable to commodity prices, which are now in decline after soaring over the last decade.

India, he points out, has, unlike China, been slow to urbanize and struggles because the IT revolution has only benefited an elite section of the population. Its per capita income of $1,489, according to the World Bank in 2012, means that it currently just makes it as a low middle-income country.

South Africa, which became a BRICS member only in 2010, has a per capita income higher than China's at $7,508, but according to Sharma, is on a downward trajectory and may soon be eclipsed by African rival Nigeria as the dominant economy in Africa.

The big question about whether China itself will eventually break through continues to divide economic commentators.

George Magnus, senior independent economic adviser to UBS, believes that China has the necessary firepower to make it into the top league.

"I think the necessary conditions are being able to build a world-beating, very competitive manufacturing capacity and, second, to be geographically close to or part of global supply chains. For the moment China ticks both boxes and a lot of other emerging markets don't. I don't think that there is much risk that China won't press on up the middle-income league over the next decade," he says.

The author of Uprising: Will Emerging Markets Shape or Shake the World Economy? also says it will still be hard for China to step up to the premier division of high-income nations.

"There are a lot of things that China has achieved spectacularly that you can only do once. You can't join the World Trade Organization twice, you can't keep piggy backing on a buoyant global economy as China has done and you can't continually transfer labor from low productivity agriculture to high productivity agriculture," he says.

"There are only three things that sustain reasonably high rates of growth, which are labor, capital and what we economists nerdily call total factor productivity, which is about technical progress.

"What China has to do is to improve the quality of its labor, which is essentially about education and making people equipped to make a more effective contribution to offset the physical drag that goes with an ageing and declining working population."

There remain many different definitions of country income status. According to the World Bank, a country moves from low income to low middle income when it achieves a per capita income of $1,035. It moves into upper middle income at $4,086 and high income at $12,616.

By this definition Russia has already achieved this at $14,037, according to the World Bank in 2012, but this is a low figure compared with what is generally accepted as being in the high-income league.

To some extent, South Korea shows the way for China on $22,590 as well as the mainland's neighboring economies: Taiwan on $20,200 and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region on $36,796.

The real aspiration, however, has to be to achieve the income levels of the firmly wealthy countries such as the United States ($49,965), Germany ($41,514), Japan ($46,720) and Singapore, with one of the world's highest per capita incomes at $51,709.

|

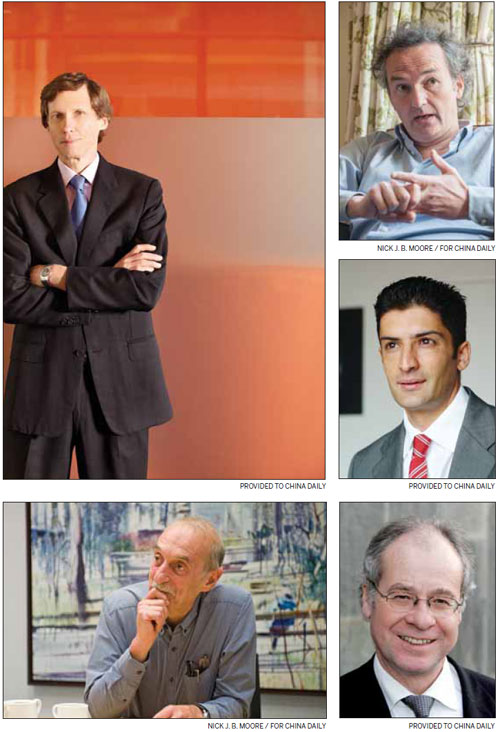

Clockwise from top left: Tim Condon, managing director and head of research for Asia with ING Financial Markets; Joe Studwell, founding editor of the China Economic Quarterly; Goolam Ballim, group chief economist at Standard Bank; Charles Gore, former head of research on Africa and least developed countries for the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development; and George Magnus, senior economic adviser to UBS. |

Tim Condon, managing director and head of research for Asia with ING Financial Markets in Singapore, says it is still not clear whether such a vast country as China can ever make it to these heights.

"If you are talking about making it the same sort of level as the United States, European countries such as the UK and Germany, that is much more of a difficult leap," he says.

"If it was just a matter of reading (former Singapore prime minister) Lee Kuan Yew's book (From Third World to First: The Singapore Story) and using it as a manual every country in the world would be as rich as Singapore. It is a very complex process of putting all the institutions together to support the economy and some countries make it and others don't."

Condon says the one thing going for China is that it has been there before, albeit nearly two centuries ago.

"China was historically in this position and had an empire for several millennia and so history would suggest it has the capacity to be a world leader again," he adds.

Joe Studwell, founding editor of the China Economic Quarterly, argued in his recent book How Asia Works: Success and Failure in the World's Most Dynamic Region that China had provided a solid basis for its economy to step up by making the necessary agricultural reforms 30 years ago unlike other BRICS countries.

"If you ignore that part of the economy - as most developing economies do because they are run by people who live in cities - you have already shot yourself in the foot."

He says whether China does make it to the next level and becomes a developed nation could depend on many of the current economic reforms being discussed now.

"China is going through an adjustment process right now and we will know over the next 24 months what sort of policy changes have been adopted."

Many see the reforms the Chinese government aims to make as crucial to the future development of the economy.

These include reforms to the banking sector, interest rate liberalization, reform of state-owed enterprises and also reorganization of healthcare and education.

Zhiwei Zhang, chief economist, China for Nomura, based in Hong Kong, says it is vital these are carried through.

"I think China's manufacturing sector is already very competitive and it is hard to increase productivity there. But many areas of the economy such as railways, telecoms and the provision of services such as healthcare and education are monopolized and inefficient," he says.

"There has been a slowness in the way structural reforms have been implemented. We hear a lot about policy guidelines but in terms of concrete action we haven't seen that much."

Zhang says there is a risk of China being stuck in some form of middle-income trap if it doesn't make progress on these issues.

"I wouldn't say yet that it is on a set path to achieve high-income developed status. There is still quite a lot of uncertainty there," he says.

Charles Gore, former head of research on Africa and least developed countries for the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), and honorary professor of economics at the University of Glasgow, says it is vital time for policymakers in China.

"I would argue there is a certain commonality to this catch-up process whether you get through it or not depends on whether policymakers understand the nature of the problem," he says.

Gore says countries tend to come up to the middle-income trap when their gross national income reaches 30 percent of that of high-income countries.

He cites a World Bank report where that ratio for China is set to rise from 19 percent in 2005 to 42 percent in 2030.

"China is at the critical point where the easier phase of structural transformation comes to an end and they just can't make the jump to the next stage," he adds.

Bala Ramasamy, professor of economics at the China Europe International Business School in Shanghai, believes that Chinese policymakers do have the ability to think on their feet, which in the end is likely to mean they come up with the right innovative policies to escape the middle-income trap.

"China has been able to demonstrate every decade or so that it can find a new path for growth. For me the recent announcement of making Shanghai a free trade zone was pretty typical of that. I think this is actually interesting and important," he says.

|

Zhiwei Zhang, chief economist for China at Nomura, says there is still uncertainty for China to achieve high-income developed status. Edmond Tang / China Daily |

|

Miranda Carr (left), head of China research at NSBO in London; and Bala Ramasamy, professor of economics at the China Europe International Business School in Shanghai. |

Most commentators - as well as Sharma - agree that China's prospects are not aligned to those of the other BRICS countries although theirs might be with China.

Certainly, China's slowing growth has affected commodity exporting countries Brazil, Russia and South Africa.

Goolam Ballim, group chief economist at Standard Bank, based in Johannesburg, says the last decade was very much the era of the BRICS.

"The noughties were the BRICS decade but the subsequent decades are going to be much more difficult for them.

"Their growth came from the fact they were infant, underdeveloped markets that were previously closed. They were primary sector dominated so they had huge capacity to grow by giving life to secondary and tertiary sectors."

Ballim says the biggest impact of BRICS has been in Africa itself.

"Twenty years ago, only 1 percent of Africa's global trade was with BRICS countries. This has risen to 20 percent with China about two-thirds of that. China's trade with Africa has increased 16 times over the past 15 years which is actually quite breathtaking," he says.

Magnus at UBS also believes the BRICS story is also now probably over.

"If you are basically looking for the next 8 to 10 percent growth story then my advice would be to look elsewhere. These guys have just had 10 years plus of extraordinary high growth rates. I think Sharma is absolutely correct in his judgment," he says.

With the development of the BRICS nations in the last decade, the idea took hold that the world was moving to a position where every country in the world would one day be developed and high income with perhaps Africa being the last frontier.

Miranda Carr, head of China research at strategic investment research company NSBO in London, says this was never likely.

"It is the same as saying that everyone in a particular country can be middle class. In most societies or structures, the wealth resides with the top 10 percent and the remaining 90 percent are exploited. You could look at this on an individual country basis or as the global economy," she says.

"You can't have everyone being a developed middle class person."

Ballim at Standard Bank, however, does believe that it is possible to have increasing global prosperity.

"In Africa there is certainly evidence that the number of people living in relative poverty has declined as growth has become more widespread because of the positive effects of globalization," he says.

"Why is it not possible for everyone to enjoy prosperity in 100 years time? For cyclical reasons because of the financial crisis the next two decades might be difficult and the pace of global development might slow. After that, however, further progress can be made."

Whether Chinese citizens continue to prosper over the coming decades and benefit from the high-income levels of a developed country is a little more nuanced, according to some.

Ramasamy from CEIBS says the reality is that some provinces and municipalities of China are already high income.

"I think if you are talking about Beijing, Shanghai, the eastern provinces of Zhejiang and Jiangsu, and the southern manufacturing centers of Guangdong, these have already broken out of the middle-income trap and are already high income," he says.

He adds, however, for the country as a whole to become high income is far more of a challenge.

"Some of the provinces, municipalities and autonomous regions are in themselves country sized. For them all to average out at high income is not going to happen any time soon.

"The per capita income of Gansu (one of China's poorest provinces in the northwest) is about $1,000, which is more like sub-Saharan Africa."

andrewmoody@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily European Weekly 07/26/2013 page1)

Today's Top News

Xi's speech underlines commitment to reform

Audit targets local government debt

Brain drain may be world's worst

Russian military to make inspection flights over US

Financial guru looks to nation's future

China-EU solar trade dispute diffused

30 killed in Italy coach accident

No time limit for Snowden's stay

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|