Etchings of the future

Updated: 2014-09-30 07:19

By Lin Qi(China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

A major exhibition of Chinese engravings, set to open in Shenzhen, promises to show how today's artists were influenced by the art form that flourished last century. Lin Qi reports.

Many contemporary Chinese artists, including Xu Bing, Fang Lijun and Zhou Chunya, majored in engraving at college. The art form, which served as a revolutionary propaganda tool in the early 20th century, is still a source of inspiration for them, no matter what the artists now specialize in.

The first national engraving exhibition, to be opened at the Guanlan Engraving Art Museum in the country's southern city of Shenzhen in October, promises to show how the art has evolved and shaped the vision of today's artists.

|

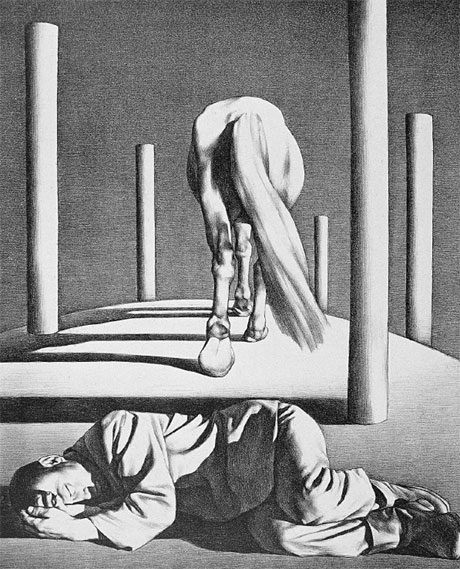

Lying Man and Receding White Horse, 1989, lithograph, by Su Xinping. |

|

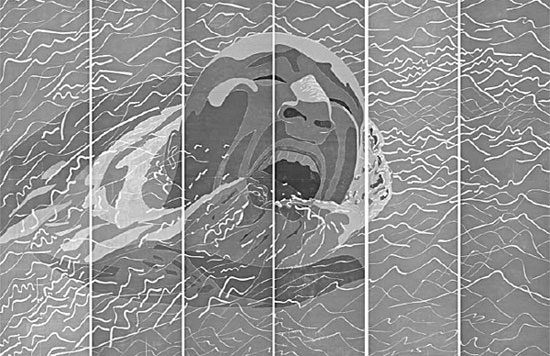

A set of six woodblock prints, 1999, by Fang Lijun. |

The exhibition will present the dynamism of engraving with four curated sections. It's expected to change people's perception of the genre as a propaganda tool and extend its reach.

"Engraving has developed fairly well worldwide. I've been to many engraving biennials and festivals abroad that are even larger in scale than contemporary art events," says Wang Chunchen, curator for the art museum at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing.

"Even though it hasn't been thriving in China, the languages and the presentation of engraving have evolved over the past three decades."

It happened alongside the rise of contemporary artists who were schooled in engraving disciplines at university, Wang adds.

In the early 20th century, engravings in China were mainly used as a medium for publicizing revolutionary events. Present-day Chinese artists, who work on plates or blocks, stress self-expression and diversity, he says.

Wang is the curator for the Philosophy of Languages section at the upcoming exhibition. It seeks to explain an artist's thinking process when he or she creates a piece.

"Xu Bing, for instance, applied a lot of carving techniques in many of his late works. But he has never restricted himself to the form of engraving. Instead, he demonstrates flexibility in incorporating multiple media that attests to the value of handicrafts and what it means to be human in his works."

The Liberated Instrument section will examine how academic training in engraving influences an artist's thoughts.

"Engraving is not used for political propaganda anymore, nor has it stayed just at the academic level. Instead it has become a liberated form that allows artists to explore all possibilities," says Kang Jianfei, secretary-general of the engraving committee under the China Artists Association. Kang is curating the section.

It will display, for example, Sun Xun's animation works.

A year after he graduated from the engraving department of the China Academy of Art in 2005, Sun, 34, established his own animation studio in Beijing. His works, usually in black and white, discuss the construction and narration of history. The animation works that will be on show were produced through a series of engravings instead of drawings.

Many artists seek inspiration from engravings or related topics. The connection can be seen in physical forms, too, and, more importantly, in the process of conceiving artwork.

The Logic Behind section displays more experimental, mixed media efforts to discuss how engravings are reflective of social transformation.

Sheng Wei, deputy editor in chief of Beijing-based Fine Arts magazine and curator of the section, believes engraving was "new media" in the era of classical arts.

"It became a public medium because a great number of messages could be reproduced and circulated. It symbolized the efficiency of communication and indicated social changes," he says.

The section exhibits pieces that embrace these features. The paper-cuttings, for example, served as message carriers during the agricultural times.

The fourth section will be a solo show of Tan Ping, deputy-director of the Beijing-based Chinese National Academy of Arts. The exhibition will reflect upon the 54-year-old's signature creations in the past 30 years. Curator He Guiyan from the Sichuan Fine Art Institute says the show is a case study on an engraving artist's interactions with time.

The exhibition will run until March 2015.

Contact the writer at linqi@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily 09/30/2014 page20)

Today's Top News

China to start direct yuan-euro trade

Protest disrupts life in Hong Kong

Slim waist fad causing problems

Americans split over role of gov't in their lives: Gallup

Spanish diplomat killed in Sudan

Independence of MH17 probe 'crucial'

Illegal assembly in Hong Kong leads to clashes

Aggrieved firms 'should go to court'

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|