Nowhere to turn

Updated: 2012-04-13 13:42

By Mei Jia (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

|

Liu Zhenyun has established a reputation for his sharp observations of city life. JIANG DONG / CHINA DAILY |

Veteran writer of 30 years says his new novel's characters speak to him. And yet, its central theme is one of man's constant search for someone to talk to. Mei Jia reports

Writer Liu Zhenyun believes the opening sections of the Analects and the Bible capture powerfully the difference between Chinese and Western societies: One is focused on man-man relations, the other on man-God connections.

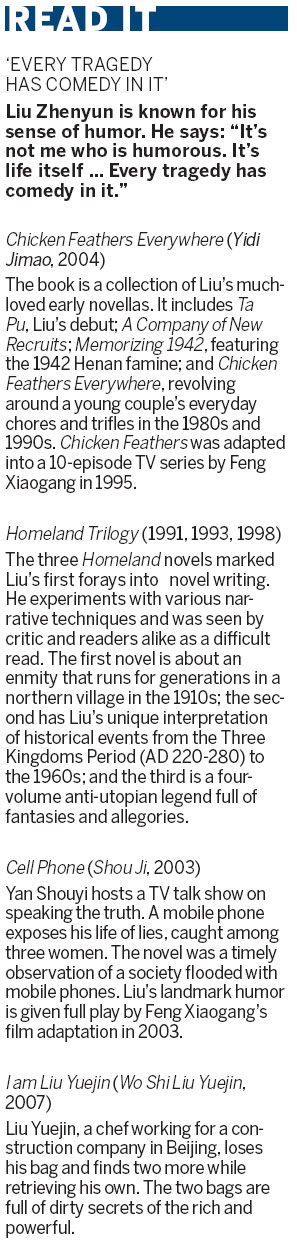

His latest novel A Sentence is Worth Thousands (一句顶一万句, Changjiang Literature & Art Press, 2009) explores man's constant search for someone to talk to.

The loneliness of a society sans religion, Liu says, is its main theme.

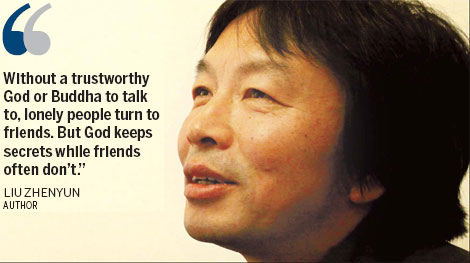

"Without a trustworthy God or Buddha to talk to, lonely people turn to friends. But God keeps secrets while friends often don't," Liu says, adding that complex interpersonal relationships in Chinese society make it harder for people to confide.

The fruit of more than three years of labor, the book has sold some 600,000 copies, Liu says. It has been hailed by critics as marking the author's return "as a key literary figure".

"Liu is a neo-realist writer who debuted with Ta Pu in the 1980s, but he went too far with the Homeland Trilogy in the 1990s," says literary critic Lei Da.

"In the new century, his works Cell Phone and Lost and Found are too in line with TV and cinema, making him unrecognizable as a novelist.

"I see him returning with this marvelous new book," Lei says.

Liu, 52, though prefers the word "transition" rather than "return" to describe the significance of the novel.

He started writing in 1982, after serving five years in the People's Liberation Army in Gansu province and studying four years of literature at Peking University.

By the early 1990s, he had established a reputation for his sharp observations of city life and the everyday concerns of ordinary folk.

His cold humor shone in Cell Phone, which was adapted to the big screen by director Feng Xiaogang in 2003, starring comedian Ge You as a TV talk show host caught among three women. The novel's drama adaptation, which focuses more on women characters, recently appeared on the Beijing stage; a TV adaptation is scheduled for May.

His cold humor shone in Cell Phone, which was adapted to the big screen by director Feng Xiaogang in 2003, starring comedian Ge You as a TV talk show host caught among three women. The novel's drama adaptation, which focuses more on women characters, recently appeared on the Beijing stage; a TV adaptation is scheduled for May.

Liu says he wants every work of his to provide a new reading experience for his readers.

But his experimentation with a highly stylized and allegorical style in Homeland Trilogy, marking a big departure from his straight and direct ways, met with mixed reviews among critics. It left many readers cold as they could not comprehend its hallucinatory, dream-like narration.

"I've been writing for 30 years and finally my characters speak to me," says the author, dressed in a black Chinese-style jacket, over tea in the same storytelling tone that he uses in his novels.

In his new novel, Liu is a listener rather than speaker. "I abandon the writer's tendency to speak; instead, I'm a witness to the unfolding story."

Set from the 1920s to the present, the novel revolves around the search of a grandfather and a grandson, the two parts of the story are titled Leaving from Yanjin and Leaving for Yanjin.

Yanjin county in northeastern Henan province is the hometown of both Liu and the main characters of his novel.

Yang Baishun, a longtime resident of Yanjin, eventually leaves to search for his lost adoptive daughter, Qiaoling. Some 70 years later, Qiaoling's son, Niu Aiguo, heads to Yanjin to trace his roots.

While many other writers have tried to describe the tremendous changes China has seen since the 1920s, Liu does so without reference to any social or political events.

"I have intentionally avoided mentioning historical events and their influence," Liu says, adding that he has tried to capture the time period he is describing through everyday-life details - like whether it is a bike, tractor or truck that is in use.

"I have tried to restore the connection between literature and life," he says.

Liu also includes in his narrative an Italian missionary nicknamed Old Zhan, who helps string these everyday details into a chorus that goes to the root of the novel's central theme.

Looking and speaking like a Yanjin resident, the missionary converts eight locals, including Yang, to whom he gives the name Yang Moxi - Moxi, being the Chinese name of Moses.

Old Zhan leaves Yang with a faith that Yang himself is unaware he possesses.

Niu's search for his grandfather and mother's past also leads him to find his own spiritual wealth.

Claiming that the character of the missionary is "the first of its kind in Chinese literary history", Liu says Old Zhan is the link that connects two societies - one with religion and another, without.

The critic Lei praises Liu for looking at the issue of loneliness among peasants, migrant workers and craftsmen, rather than just at intellectuals.

"To feel alone is not a privilege," Lei says. "Liu analyzes it as a universal human experience and sees it as arising out of China's unique history."

Another critic Bai Ye is also impressed by Liu's attempt to portray loneliness. "Liu's got unique and powerful storytelling skills. The novel is a masterpiece."

The author himself sees his new novel as "so far the best-written and the one I'm most proud to give to friends".

It is slated to be adapted for TV this year. His next novel will feature, for the first time, a female lead character, Li Ailian, a village girl who resumes her education at the end of the "cultural revolution" (1966-76) in the novella Ta Pu.

"I'm interested in seeing how far she has come after so many years," Liu says.

Today's Top News

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|