It's kids' stuff

Updated: 2012-02-07 13:14

By Mei Jia (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

|

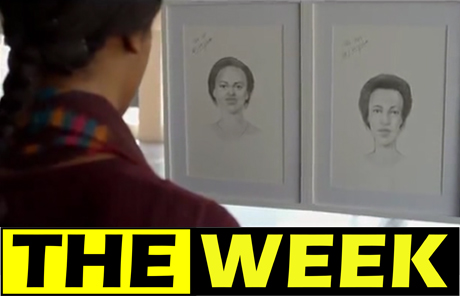

Beijing pediatrician Wang Yinglin highlights practical tips based on traditional Chinese medicine in childcare in his new book. Jiang Dong / China Daily |

|

Wang Yinglin's approach to childcare is based on the tenets of traditional Chinese medicine and is gaining converts. Mei Jia reports.

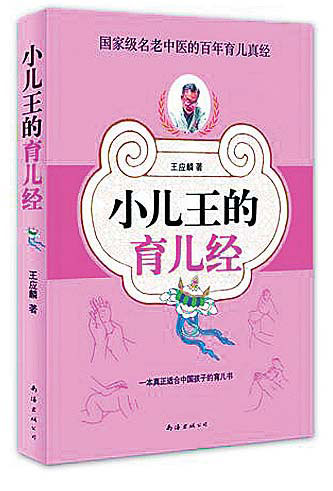

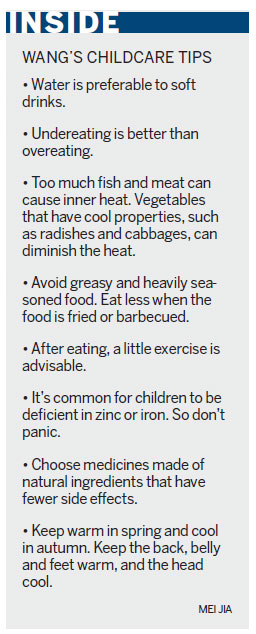

Two of the most common mistakes Chinese parents make raising children is overfeeding and dressing them in too many layers of clothing, a traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) doctor claims in his latest book, Wang's Guide to Raising a Healthy Child.

Wang Yinglin, 73, is one of Beijing's best-known pediatricians.

"Many of the common illnesses experienced by children younger than 15 are caused by exceeding the amount of nutrition and clothing they require," Wang explains.

Since the country's family planning policy generally produces just one child, youths are given "close and intensive care" from six grown-ups (parents and two sets of grandparents), Wang says.

A national history of malnutrition and even starvation makes parents more likely to overfeed their children in a time of growing affluence, the doctor adds.

Based on 48 years of TCM pediatrics, Wang's book advises food therapies and massages, in addition to guidelines for the treatment of common diseases with Chinese herbs.

Wang's childcare theory centers on protecting the functions of the stomach.

"Too much food overburdens the digestive system and causes internal heat in the body," he says.

According to TCM theory, yin (cool) and yang (hot) energy need to be in balance for good health. Imbalances make the body "apt to the invasion of coldness, which results in fevers, coughing, runny noses, vomiting and more", Wang explains.

Chinese people have long believed that eating to 70 percent full is one of the keys to good health. Parents should keep this age-old wisdom in mind when they feed babies, Wang adds.

Since children have more of the active yang energy than grown-ups, they don't need to wear as many layers as adults, even in winter.

Wang suggests parents ensure their children wear one item of clothing fewer than themselves.

"There was time when people believed Western medicine was most effective," Wang continues. "Now I see more Chinese turning to TCM, mainly because there are less side effects to herbs."

For instance, a Beijing mother, surnamed Xu, visits Wang because she is concerned about her child's frequent bed-wetting, which Western medical advice failed to help.

Wang found the girl had a good appetite and was full of energy, but suggested she do more exercise before bedtime and eat less.

|

In addition to prescribing TCM, Wang advised the mother not to help the child urinate at night but instead encourage her to do it herself. His book also suggests drinking less water before bedtime.

Childcare books have dominated the best-seller lists in recent years, but editor Zhao Pingyu says that what makes Wang's book unique is its focus on the age-old wisdom of TCM.

As to the rising problem of childhood obesity, Wang encourages breastfeeding and regular eating habits.

He says the fast pace of life today means children do not have the time for good breakfasts and lunches, which leads to overeating at dinner.

"This habit harms the stomach and results in dyspepsia, especially if it is a fast food diet full of extra calories, which are hard to digest the result is obesity."

His solution is a fixed diet.

In treating common diseases, TCM takes into account the overall health of the child rather than curing a specific illness, Wang says.

"Western medicine gives much the same sets of medicines for pneumonia, while TCM traces its origin," he says. "A variety of herbs enables the medicines to deal with problems at their roots, whether they're for compensating, for growing, for releasing or for easing the symptoms."

Though Wang comes from a family that has practiced TCM pediatrics for four generations, Wang says he did not originally want to follow in their footsteps.

"My teenage idol was Xu Xiake (a Ming Dynasty explorer and geographer). I wanted to be like him, to explore," Wang says.

"So when I signed up for college in 1958, I took geology and TCM because of my father. But fate favored the latter, and I began to follow my family's path."

Even so, Wang says he still enjoys traveling and exploring, and has also developed an interest in computers.

Wang has practiced at pediatric hospitals in Jiangxi province and Beijing, and is one of the country's 500 veteran TCM doctors. He is a consultant at several clinics and sees an average of 40 patients a day.

He has also been training students and writing books to pass down all he has learned.

Today's Top News

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|