When three colors add up to make the No 1 artifact

Updated: 2011-12-01 07:40

By Zhang Zixuan (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

Editor's Note: Every week we look at a work of art or a cultural relic that puts the spotlight on China's heritage.

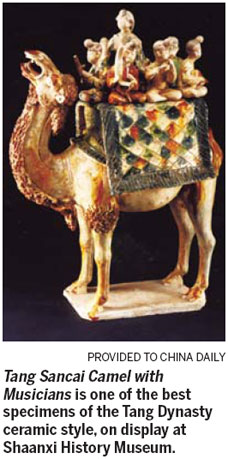

A camel raises its neck, neighing.

Its humps are draped with a colorful blanket atop which ride eight musicians - a woman sings and dances in the middle of the seven instrumentalists.

The image is of a music troupe from the Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907), the cultural zenith in China's imperial history. The prosperity that led to this artistic blossoming came about because the dynasty's capital Chang'an - now Shaanxi's provincial capital Xi'an - was the eastern terminus of the Silk Road.

The music troupe's image was rendered in the colored glaze of Tang sancai, the ceramic style of the time.

Tang Sancai Camel with Musicians - excavated from a Tang-era tomb in Xi'an's Zhongbao village in 1959 - is one of the best specimens of this genre at Shaanxi History Museum.

|

Sancai - literally, "three colors" - refers to the most commonly used green, yellow and white glazes. Some ceramics from the period are covered with a rare blue and an even rarer black.

The body of sancai ceramics was made of white clay, which was coated with glaze and fired at 800 C. Adding copper turns the glaze green, and iron makes it brownish-yellow.

As one of the most representative Tang artifacts, sancai often appears in TV dramas about the dynasty.

But historians scoff at the idea of them being placed in such places as living rooms or bedrooms.

As Shaanxi History Museum researcher Wang Shiping puts it: "Although Tang sancai ceramics are of high artistic value, they were mostly used as burial objects that showcased wealth. So living people wouldn't use them as home decorations."

Elaborate funerals were typical among Tang nobility.

Because sancai ceramics were funerary objects, they were buried and forgotten until 1905, when a large number were unearthed as the Qing government built the Longhai Railway.

But the workers destroyed most of them to avoid being cursed. Most of the rest were sold overseas.

In 1989, a sancai horse sold for HK$49.55 million ($6.36 million) at a Sotheby's London auction. It was then a record price for a Chinese artifact.